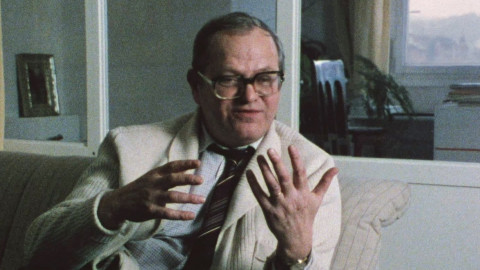

Milan Šimečka, 20. 1. 1988, Prague, Czechoslovakia

Questions to the narrator

- 00:11Could you describe for us the main stages of the normalisation of Czechoslovakia?

- 02:08What were the main ingredients of the Czechoslovak normalisation? You have called it ‘the restoration of order’. What kind of order was restored and what were the ingredients of the restoration?

- 03:21And the people who broke the rules in the first place were the people who had power? After all, the Prague Spring started from the bottom.

- 05:38Who carried out the process of normalisation? What were the forces behind it? And where did they find the people to do the job?

- 08:04You spoke of civilised violence. Is this a Soviet import, or is it an original Czechoslovak creation?

- 09:48Could you give us a personal example of what happened to you in the normalisation process?

- 11:55Is it all possible because the state is the only employer? So the pressure is not done directly by the police but it’s done through the personal officer.

- 14:21In other words, what I mean – would the reform communists of 1968, would they have accepted the multi-party system? Would they accept it in genuine pluralism?

- 15:15The Czechoslovak Communist Party has been purged of half a million people. Who has replaced all these people who’d been sacked from jobs? Who are the people in power now?

- 16:52And what about today? Do you think it’s possible to have perestroika, reconstruction of the economy, without having a political change?

- 18:13So what is the state of Czechoslovak society today? What is the damage done of the last fifty years?

- 18:52But what would the society need to start organising on its own? To start organising independently from the state?

- 19:54One of your early works was on utopia. What has happened to the socialist' utopia?What has happened to the marxists' dream?

- 22:10Do you think that Gorbachev’s reforms could have opened the system, or could they simply improve it? Simply make it work better for the party?

- 26:05Are there concrete signs of it? Is there some evidence that things are changing in the right direction, in the direction that you would wish?

- 15:00Do you think if the Prague Spring hadn’t been interrupted by the invasion it would have gradually developed into a democratic, an open society of the Western European style?

Metadata

| Location | Prague, Czechoslovakia |

| Date | 20. 1. 1988 |

| Length | 27:51 |

Watch and Listen

| Full video (mp4, 27 min) |

| Preview video (mp4, 2 min) |

| Audio track (mp3, 26 min)

|

TranscriptPlease note that this transcript is based on audio tracks and doesn't have to match exactly the video

Jacques Rupnik: Could you describe for us the main stages of the normalisation of Czechoslovakia?

Milan Šimečka: In the first stage it was naturally primarily anxiety about what would happen next. People had only experienced such a situation in much worse times once in the past, so there was a lot of rumour around. But I think that a certain role was also played by the mood of the Czechoslovak people, who in a very inconspicuous manner enforced more polite treatment. So for instance the next government, which had already been determined in advance, was eventually not elected, and a transitional period was established, which many people including myself thought would not be so horrible, that some principal aspects of the revival process could be maintained. But later it obviously turned out that the process in a way took the same inevitable course as it did elsewhere in Eastern Europe, that basically the same type of order as earlier was re-established, but in a much rougher and more apparent shape. The second stage began after the replacement of the secretaries of the Central Committee, when the revival group was fully replaced. They had been enlightened to a certain degree, and then they were replaced by people who only obeyed orders.

What were the main ingredients of the Czechoslovak normalisation? You have called it ‘the restoration of order’. What kind of order was restored and what were the ingredients of the restoration?

It is only the figurative meaning of the word. It used to be said then that order had to be restored, the only real argument at that time was that there was some sort of disorder in Czechoslovakia. The year 1968 was a year of disorder because things happened that no one was accustomed to, especially the party officials. People spoke their minds, they spoke freely, there was no censorship in the newspapers. This all led to great confusion in the minds of people who had become accustomed to some rules that in this system had to be obeyed. The rules were suddenly abolished, and they sensed disorder. But it was primarily felt by those people who had the rudiments of the system inside themselves.

And the people who broke the rules in the first place were the people who had power? After all, the Prague Spring started from the bottom.

Certainly. To put it bluntly, I don’t think that all of them then thought that this kind of disorder would occur. They probably incorrectly evaluated this nation. It is an issue which also occurs today and stretches back through all its history. In this sense, I would continue to what we can expect today and what is happening in the Soviet Union. The problem of democratisation which they have in Russia today is much simpler there. When we say ‘democratisation’ here, everyone means the democracy that their grandfathers or fathers experienced, or they mean the standard democracy of Western European type. That they should be able to choose from two candidates, it’s quite a ridiculous question here, because even a hundred years ago they could already choose from three or four candidates for the municipal council. This is how Masaryk was elected a member of the Viennese Diet just one hundred years ago. And that’s the problem, that all the questions that arose as questions of the revival of socialism were mixed with the traditions here, and that’s why it ended up like this.

Who carried out the process of normalisation? What were the forces behind it? And where did they find the people to do the job?

I am aware just like you are of how many, let’s say, sophisticated considerations are made in the West, especially in institutes doing Kremlin research, of how it all happened. Even though it may not be right, I think that the whole matter can be simplified to fully understandable notions. In all the systems in Eastern Europe, a certain kind of privileged class arises over the years. Milovan Djilas calls this a class, but it’s not a class in the Marxist sense with ties to means of production. It is a privileged layer which acts like a class, cares for its interests and protects them. They’re not only power interests, they are also interests which create strong economic privileges. People in official positions are better off than those who do not belong to the privileged classes. It was totally clear that in 1968, and now also Dubček mentioned it in his interview, many officials, i.e., people who were part of this privileged class, realised that in the new environment they would not necessarily have to be elected, and would lose their privileges. And among them rose all those who are now spoken of as the sound core of the party. There was nothing else in it. It is natural that there could be several idealists, or there were hundreds of them, who thought that this was no longer socialism. But in fact it was the same process which you can see today in the Soviet Union, where the opposition is strong because it really represents a class with its own interests.

You spoke of civilised violence. Is this a Soviet import, or is it an original Czechoslovak creation?

I think it is linked to the time. The 1970s even in the Soviet Union weren’t of the kind where a brutal political culture would apply as it did, for instance, in the 1930s. So there was probably no such pressure on Czechoslovakia even from the Soviet Union that the people who had been behind the revival process should be gotten rid of, which probably would have happened twenty years ago, like it did in 1956 in Hungary. But I believe that those specific forms of civilised violence were invented here in Czechoslovakia. This is related to the fact that society here is organised in a certain traditional Central European way. To remove someone from society or make him a second-class citizen, you don’t need violence, just a decree, a piece of paper, is enough. Everything that happened here was written on a piece of paper. People would receive decrees: “Do whatever you want, now go and look for a new job”.

Could you give us a personal example of what happened to you in the normalisation process?

Thousands, tens of thousands of people could tell you how it all happened. I personally didn’t have the impression that some brutal violence was committed against me. No one caught me, expelled me from the university where I taught, no one closed the door for me at the university. It simply happened that the academic officials began to tell me how horrible it was that I was still there, what difficulties they had to face, that for instance a pay rise for university lecturers was in preparation, but until I went the faculty wouldn’t get it. So I worked there as the cause of misfortune of all the other people who were very close to me, whom I considered to be friends and whom I honoured in a certain way, and suddenly I saw that I was the man who was preventing their families from living better. So I simply said, give me the paper to sign and I’ll leave and work as a driver. Of course some people filed lawsuits, but that was meaningless. But the cases when people were imprisoned were cruel at that time. Then there were sentences of five or six years for a basic inability to come to terms with what was happening here. And the reason was often merely participation in a petition, something that was repeated from 1968. Only later, at the beginning of the 1980s, did this begin to wane. But Havel, Dientsbier and all the others were still sentenced to four or five years.

Is it all possible because the state is the only employer? So the pressure is not done directly by the police but it’s done through the personal officer.

This is symptomatic for all of Eastern Europe. You won’t find a single place in the whole country where you would be able to hide in the private sphere. Everything is controlled by the state. The state is not only the employer, the state pays your health insurance, the state pays your doctor, the state sends you for recreation, issues you a passport. At every single moment you are in a certain way dependent on the state. And then, at the beginning of the 1970s, the state showed this quite clearly to everyone: If you behave well, you will get everything we are able to give people. If you don’t behave well, we will take away this and that from you. And it went on like that, and that’s the cause of the fact that in Eastern Europe if people are not really hungry, or forced to go onto the streets like in Poland, no mass protest movements basically exist.

Do you think if the Prague Spring hadn’t been interrupted by the invasion it would have gradually developed into a democratic, an open society of the Western European style?

The basic feature of this question is doubt.

In other words, was this just democratisation, or was it going towards democracy?

How I see this today: I think that everything that happened was premature from the viewpoint of Eastern European history. If in the main country, which is the Soviet Union, thinking does not develop to such a degree as to be able to tolerate any democracy, it seems useless for anyone in the satellite countries to try to do something like that. It’s a hypothetical question – if they had let us alone.

In other words, what I mean – would the reform communists of 1968, would they have accepted the multi-party system? Would they accept it in genuine pluralism?

As I know them today, twenty years later, they would. But they are all people who underwent some development. At that time, perhaps not even Dubček or many staunch party and government officials were probably able to imagine not only true pluralism of the Western type but even some, let’s say, socialist pluralism which Gorbachev now speaks about. Twenty years later, seeing how thinking has developed in Eastern Europe, I am convinced that also Dubček and all the others would have been able to come to that.

The Czechoslovak Communist Party has been purged of half a million people. Who has replaced all these people who’d been sacked from jobs? Who are the people in power now?

Of course there was the core of people you know by name, such as Bilak and many others, who couldn’t stand the principle of democratisation, it was against their convictions, and as I said, it threatened their privileged position. All the others who became the basis of the normalisation were people who had welcomed the revival process and the year 1968. I could name plenty of officials whom I know in person and who spoke to me in 1968 and also after the invasion in such a manner for which today they’d be sentenced to at least three years for incitement to riot. All these people have changed their minds, as they understood that if they do not agree with what the Soviet Union wants to implement in this country they would become outcasts, just like we are today, and so they simply changed. But these people could not change their way of thinking. A certain pragmatic period came after that, during which if someone wanted to keep his position as an official, he did whatever was necessary within the framework of the system.

And what about today? Do you think it’s possible to have perestroika, reconstruction of the economy, without having a political change?

I believe that there is only one answer to this question, and that even in the Soviet Union they realise that any change or reconstruction of the economy is impossible without a political change, at least in the sense that it is necessary to get the whole awful stagnating layer of the population moving. That’s the worst problem they have. It’s also true for us, for the Poles, perhaps a little less for the Hungarians, it could be less true for the Soviet Union, where especially the intelligentsia is euphoric today. But after the local experience we are ruled first of all by apathy, lethargy and distrust, terrible distrust of any changes in the sense that the people who call for the changes do not mean them seriously. That’s the basic issue. They realise that if they want to revive the national economy they must make people interested in how they work. But the people are not very interested in that.

So what is the state of Czechoslovak society today? What is the damage done of the last fifty years?

The worst, as I have already said, is the absolute distrust, apathy, the inability to imagine that the same people who crushed the reforms, revival, democratisation and everything that had been here in 1968 would sincerely want to re-establish all that. And that’s the cause of the enormous distrust.

But what would the society need to start organising on its own? To start organising independently from the state?

I heard you speaking to Václav about that. What we would need is room for real public life as we knew it from the old times. It wouldn’t have to specifically mean that there would be another political party established in opposition, but free space would be made for civil initiatives, and especially for the youth to have their say, to make people again understand that it makes sense when someone is interested in something. The majority of people today believe that it makes no sense because it will all be wiped away.

One of your early works was on utopia. What has happened to the social […]?

I have always believed that at the beginning no terse theory would probably lead to a great movement, especially not in Russia where civil war probably could not have been won without people who had imagined in primitive forms that paradise would come. This always happens and it probably did there, too. I am convinced that a similar utopia worked its magic here, too, at the beginning. There is no other explanation as to why so many enlightened, intelligent and well-educated people joined the Communist Party. When you say this to young people, they say: “Were they crazy? They really didn’t know anything? How was that possible?” After all the years, it’s been forty years here, when the system wiped off itself one utopian layer after another, when they were falling off it like leaves, it has eventually become bare and can be “seen through”. Everyone can see today whom it serves, what it is for, why it is. In this sense, utopia is totally dead today. Among the youngsters or middle generation, you won’t convince anyone today to become enthused by the thought of sudden and quick reconstruction of society, of creating some paradise. That matter is gone. It might perhaps still work in other countries, maybe in Central or South America, but not here in Central Europe. Immense sobriety has come.

Do you think that Gorbachev’s reforms could have opened the system, or could they simply improve it? Simply make it work better for the party?

I actually care very little for the word “system”. I know the forms in which it is used in the theory in Western Europe which states that “system is system”. It is rather something that is with us here, that developed in the course of history, has its specific features and nature. Despite all that, I don’t think that the question is that we either change the system or nothing can happen at all. I’ve always said that for us who live here, even a small change to the system is a miracle. It is maybe ridiculous to mention it, but the fact that I can go to Prague is very pleasant for me, as before I often could not. Just three days ago I was being watched by the police and told that I shouldn’t come here. So my understanding of that question could be primitive when I speak of what can be improved, and what Gorbachev can improve. I would be happy if I could receive mail, if the letters I send arrived at the correct address. If I could make a phone call knowing that a third person is not listening in. Such things are extremely important for us and are also important for the others, not to be fooled, not to have that constant lie ruling us. If Gorbachev hadn’t succeeded in anything else but in removing lies from the Soviet history which it is based on, in having people and nations who live there find again their true national identity, it would be a great thing. And we don’t know what it will do to the system. And while the system we are speaking of now needs a lie to exist, if that lie is removed, the system will also cease to exist. I have no doubt that in Russia as well as here it is probably not possible to change the system in such a way that we sell all our national enterprises to General Motors or another company. No one would actually even buy them, they are not functional, they would just make a loss. What is certain is that we do have something here, something that has been made in the past, and it is also certain that things can be done with it which we may have no idea about today, anyway there are certain prerequisites for that. But I in no case think, as is often claimed in the West, that Gorbachev intends, or it might happen, that communism, and I don’t like the word because it’s not communism, would strengthen itself and threaten Western Europe or the United States much more. That’s nonsense. It can’t go that way. Every single move that brings the system, or the conditions in the Soviet Union, closer to truth will provide for better conditions also for general communication in Europe and elsewhere.

Even here in Czechoslovakia?

Also in Czechoslovakia.

Are there concrete signs of it? Is there some evidence that things are changing in the right direction, in the direction that you would wish?

We can’t see any signs yet, at least not substantial ones. Of course I welcome these trivialities. For instance, no one has for a long time been sentenced for a thought crime, for which in the past there would be sentences of up to five years. That happens no more, and that is great. There are a couple of minor things, but otherwise they are only words, words, words. What has changed is the vocabulary which they use, but otherwise nothing has changed. But even though this country has always been so derived from the Soviet Union, there is no other country in Eastern Europe that would be so dependent on it, even with its thinking and everything that was happening here, a true copy, I still do not think that it is possible to create another Albania here. If things in the Soviet Union continue the way they are now, it will also probably make its way through in slightly different ways here.

Milan Šimečka (1930–1990)

Czech and Slovak philosopher and literary reviewer. He graduated in Czech and Russian literature from the Faculty of Arts in Brno in 1953 and worked as an assistant at the Comenius University in Bratislava, where he lectured in Marxist philosophy at the Academy of Music Arts from 1957 and from where he also habilitated. He addressed the history of philosophy, wrote literary reviews and political essays, and social utopia became his lifelong topic. In the period of dissent, he analysed the methods of functioning of totalitarian systems and “great” as well as “small” everyday politics. His works are a remarkable chronicle of the time. He was a member of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia, but after the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia in August 1968 and the rise of the “normalisation of society” under President Husák, he was expelled from the Party, forced to leave the academic sphere and did manual and auxiliary jobs. He published his works in samizdat and exile journals. In 1981–1982 he was imprisoned for thirteen months for his anti-regime attitudes. During the Velvet Revolution in 1989, he assisted the Verejnosť proti násilliu movement, and in 1990 President Václav Havel appointed him chairman of the presidential Council of Advisors, but he died soon after. President Václav Havel awarded him the Order of Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk in memoriam in 1991.

From his works: Social Utopias and Utopians (1963), The Crisis of Utopianism (1967), Restoration of Order (samizdat, Petlice Edition, 1977; Svědectví 1978), Letters on the Nature of Reality (samizdat, Petlice Edition, 1982), Our Comrade Winston Smith / Czechoslovak Epilogue to 1984, the Novel by George Orwell (samizdat, Petlice Edition, 1983; Svědectví 1983), The Big Brother and Small Sister / On the Loss of Reality in the Ideology of Real Socialism (with Miroslav Kusý, samizdat, Petlice Edition, 1984), European Experience of Real Socialism (with Miroslav Kusý, New York-Toronto, Naše snahy, 1984), Circle Defence / Records from the Year 1984 (samizdat, Petlice Edition, 1985; Listy 3, 1985), End of Stillness (Lidové noviny, 1990).

Links: