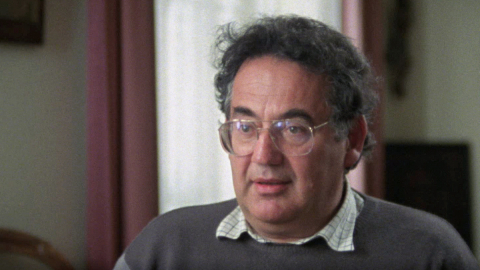

Jiří Sláma, 28. 1. 1988, Munich, Germany

Questions to the narrator

- 00:13To what extent were the Czech economy and the other socialist economies directed from Western trade to the East?

- 04:41Why were all the basic economic relationships in Soviet-style systems deformed, distorted?

- 06:46What limits does party control of the economy set on reform, and what sort of changes might happen within the system?

Metadata

| Location | Munich, Germany |

| Date | 28. 1. 1988 |

| Length | 10:16 |

Watch and Listen

| Full video (mp4, 10 min) |

| Preview video (mp4, 1 min) |

| Audio track (mp3, 14 min)

|

TranscriptPlease note that this transcript is based on audio tracks and doesn't have to match exactly the video

To what extent was Czech central planning based on the Soviet model, and could you give some examples of the absurdities that it gave rise to?

I was lucky – or unlucky – to have been, during my university studies of economics in 1950 and 1951, employed at the Workers Planning School where officials of the Communist Party, of all ages, mostly workers, were being prepared for work in managing the economy, especially at the State Planning Commission. And so I was able to observe those first beginnings of Soviet planning in Czechoslovakia when it was being introduced. I remember that in 1950 or so, or 1951, we got our hands on the first guidelines for drafting the plan in Czechoslovakia according to the Soviet method. And it was actually nothing more than a translation of the Soviet guidelines. The people who prepared it perhaps had no time, were unable to or couldn’t be bothered to change things which had no validity whatsoever for Czechoslovakia. For instance I can remember that one of the headings in the work plan stated “Number of reindeer herdsmen in Czechoslovakia”, while there are no reindeer in Czechoslovakia. Or it was also about fishing at sea – another thing that did not apply to Czechoslovakia. It was of course very easy to remove these things, and they did not appear there in the following year. But those more essential, so to speak, replicas of the Soviet method, those remained there for a very long time.

Could you give me two examples of the distortion of central planning – your bread and steel example?

Yes. Of course, I could give you many examples of those, let’s say, accidents in the Czechoslovak economy which occurred as a result of adopting Soviet planning and managerial systems. I remember two which are of more general significance. When food rationing in Czechoslovakia had been abolished and the official market prices had been adjusted, the price of bread was set very low. And the reason for this was that social aspects had played a major role in the notions of those central officials who set the price of bread. However, bread proved to be so cheap that it not only failed to cover its production costs and, in addition, for people who kept pigs or other domestic animals it was more profitable to feed them with this bargain bread than find some other source of nutrition. It was a few months before this came to light and before people realized that appeals to conscience were not enough, that it had to be done in a different way – by increasing the price of bread. The price of bread was then increased. This is an example which shows that all that were used were certain social conceptions, with no consideration for the economic ramifications. It could not have happened in a free market economy that bread would be sold for half its price unless it were subsidized, and it could not have been sold without regard to these distortions in consumption. Yet in this system where politics came first and where the party leadership thought: “We have everything in hand, we can control everything”, this was a very very typical development. This is but one example.

To what extent were the Czech economy and the other socialist economies directed from Western trade to the East?

I can demonstrate this taking Czechoslovakia as an example. After all, of all the East European countries, Czechoslovakia was the most strongly orientated towards the West. I am not counting East Germany in this, as it was a part of the German economy. And this re-orientation, this orientation towards the East took place in all the countries, but for Czechoslovakia it represented the greatest change compared to the pre-war situation. The other countries, such as Hungary or Yugoslavia, were let’s say mainly agricultural, while Czechoslovakia, and the Czech lands above all, were industrial and were very closely linked to the economies of Western Europe, to Germany most of all, of course, in other words to its closest neighbour. And all that suddenly changed; it had to change from the point of view of the Soviet leadership and the other communist leaderships because it was necessary to form a large, powerful bloc with the Soviet Union and to have such an Eastern foreground. I can demonstrate it with the issue of steel in Czechoslovakia, and I think this is a typical example. In the economic conceptions of the day steel was deemed to be the basis of industry, although even then it was starting to be nothing more than a historical basis – it was important for the machine industry but not for the electronics that came later. Thus in Czechoslovakia efforts were made to increase the steel production, for which Czechoslovakia had good conditions and traditions. However, for that you first need coke, coal and ore. And that orientation towards the East, towards the Soviet Union led the decision to have large steel works built in Eastern Slovakia, practically on the border with the Soviet Union. This certainly had its strategic military reasons and even certain economic ones, as ore came mainly from the Soviet Union whereas coke and coal came from around Ostrava, where good use of the railway could be made. So there was certain rationale here; nevertheless it is an odd case where huge steel works were built at a location where there was neither steel nor ore. And as far as the volume of steel and iron that Czechoslovakia was supposed to produce is concerned, this is another example of how the centralistic system works. Normally, in a free-market economy, it is not possible to sell steel in a country for a much higher a price than it is sold at in a neighbouring country. Of course it is possible to defend this by claiming protectionism and preventing Japanese steel flooding the United States market, but even this is already a certain distortion of the free-market economy. This Eastern system is simply the world champion in protectionism, which was why in Czechoslovakia steel started to be produced in such quantities and at such costs that no one could compete on the world market with products made from it. Yet the purpose was not to export these products to the whole world, but only to Eastern countries. So this shows how that notion about not having to consider the real cost and price relations simply distorted the economic structure, of course in accordance with the leadership’s political goals. And one more remark: That forced re-orientation of the Czechoslovak economy and other economies in a direction which was, let’s say, economically irrational, was only made possible by stripping the companies of their autonomy. Autonomous companies would have never taken that direction. However, when they did not have to be responsible for what they were manufacturing, when everything was done out of one budget, then it was possible to have those things introduced in the economy.

Why were all the basic economic relationships in Soviet-style systems deformed, distorted?

That is again to a great extent connected with the previous questions. The idea arose, or the leaderships of the communist parties thought, that they could have plenty of freedom in what should be done in an economy that was under their control. It seemed that there were almost no limits on setting economic targets. If, for example, it had been decided that land would not be sold and that it would have no value, then land really did not have any value. And enterprises which were built on that land did not bear the burden of costs, did not have to pay any rent for that land. Similarly, once it had been decided that wages would be changed and there would not be any so-called breadline wages, it was possible simply to pay such wages as were deemed fit. And it was not obvious that it was impossible to do these things forever, arbitrarily, regardless of certain economic relationships. In the case of bread, as I have mentioned, it became clear within months that it would not work. But in the case of steel, and land, and wages, and in other cases it took much longer. That is the connotation. I guess for us in Czechoslovakia, for those people who did it and believed in it at the beginning, it lasted from something like 1949 to 1955, 1956, so seven or eight years before these connotations were at least partially recognized and before changes started to be contemplated.

What limits does party control of the economy set on reform, and what sort of changes might happen within the system?

I think this question again relates very closely to the previous ones. As long as it is necessary to pursue political goals within the economy, goals which are from an economic point of view as irrational as the examples I have provided, then the system of management must be centralized; until then, companies cannot be autonomous, until then, the party has to have total control over society and the economy. That was the first stage in the development of this system and these countries after World War Two, although we may differ in opinion about the substance of those goals – whether they were good or bad, that is another question. The truth is that from the point of view of the managerial mechanism these goals demanded centralisation. Nowadays, the Soviet Union in particular, on which everything depends in Eastern Europe, is starting to revise, in my opinion, her fundamental long-term economic and political aims. This is how I see Gorbachev’s reasons for the current reform. Nowadays the goals are different. And different goals, goals which are far more rational, far more fitting for the geoeconomic and geopolitical circumstances of the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe, no longer require this centralistic system, designed to force something unnatural upon the Soviet Union and those countries. So a revision of goals leads to the possibility of a revision of the system itself, which means the limits of party control are now different from what they used to be. If these goals which, as they imagine, development should be based on, are that independent enterprises would follow them, there is no longer the need for centralistic control and party control. I’d say that this means that herein lies the possibility of modifying the system, of rationalizing it to a certain extent, of changing the balance between political and economic aims. Nowadays this is all apparent in the Soviet Union and other countries. It is all moving. I think what we were envisaging in Prague in 1968 has returned and that in this one country, a country dependent on the Soviet hegemony, we also wanted to change the goals, even though we were unable to touch upon the goals of the bloc as a whole. And we saw the connection between changing the goals and changing the system. That was possible within the framework of a new policy and new goals.

Jiří Sláma (1929)

Economist

After finishing grammar school, he enrolled at the University of Industry and Chemical Technology in Brno (1945–1949), from where he switched to the Faculty of Economics at the University of Political and Economic Sciences in Prague (1949–1953). After that he worked as an assistant lecturer at the Department of Economy of Industry of the University of Economy in Prague, from where he obtained his post-doctoral degree in 1959. He was a member of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia from 1946 and in the 1950s he proactively participated in youth and party organisations. After the Prague Spring of 1968 and its suppression by the Warsaw Pact armies in August 1968, he undertook an internship at the Institute of Economy in Vienna. He did not return to Czechoslovakia and in 1970 he and his family settled in Munich, where he worked as a scientist at the Eastern Europe Institute (Osteuropa-Institut) in 1972–1992, also focusing on the development of the Soviet economy. He published essays and articles on econometrics and statistics in exile journals such as Listy and Národní politika and was one of the founding members of the Society to support research into Czechoslovakia. After the fall of the Iron Curtain and the subsequent social changes, he commented upon Czechoslovak and later Czech domestic policy.

A selection of his commentaries was published in a book entitled Do exilu a z exilu domů. Publicistická žeň z let 1968–1993 (Into Exile, and from Exile Back Home: An Array of Commentaries from 1968–1993; Brno: Doplněk, 1998). His other studies include Analýza výsledků voleb na Slovensku před a po druhé světové válce pomocí statistických metod (Analysis of Election Results in Slovakia before and after World War Two Using Statistical Methods; München: Osteuropa-Institut München, 1979) and Parlamentní volby v Československu v letech 1935, 1946 a 1948 (Parliamentary Elections in Czechoslovakia in 1935, 1946 and 1948; München: R. Oldenbourg, 1986; Praha: Federální statistický úřad, 1991). His contribution to the collection published to mark the 65th birthday of the historian Karel Kaplan (ed. Karel Jech, Praha 1993) was Statistický rozbor československých parlamentních voleb 1935, 1946, 1990 a 1992 (Statistical Analysis of Czechoslovak Parliamentary Elections 1935, 1946, 1990 and 1992).