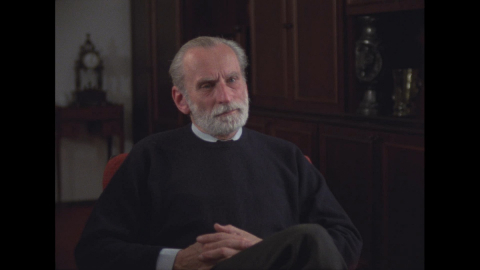

Jacek Woźniakowski, ?

Questions to the narrator

- 00:14The influence of the church is growing steadily in Poland over the last decade. Can we have a situation where the defeat of the society brings about also gains for the church?

- 00:59But you wouldn’t consider for instance that there was an element of compensation for the crushing of Solidarity in making new concessions or trying to seek a new modus vivendi with the hierarchy of the catholic church?

- 02:28For forty years Polish intellectuals have tried to become independent form the state. How independent are they really from the catholic church?

- 04:05For forty years Polish intellectuals have tried to gain independence from the state, from powers that be, from the Marxist ideology that the state tried to impose. Today Marxism seems bankrupt, the powers that be have no ideological influence. On the cont

- 06:26Are there any left intellectuals today in an entrenched camp?

- 07:45But let me bring that West think that there is a decline of religious belief in the West, in the secularized West. Whereas on the contrary there is a religious fervour in the lands where communism is in rule.

- 08:36But for the mass of people - especially after the defeat of Solidarity - you had to choose your camp.

- 09:36Yes, but at the same time the church made gains as an institution. There is constantly this dual role of a church as a spokesman for society and a church as a religious institution in the proper sense of the word.

- 10:19Now Cardinal Wyszynski once said that Polish church is closely watched by the security organs but that it is also closely watched by Polish society. That is therefore this constant tension of the church between state and society. How has this dilemma been

- 11:58What has happened to the influence of the party among the intellectuals?

- 13:07What was a reason for that split between the party and its intellectuals?

- 13:34Do these divisions between those who used to be communist and those that are closer to the church, do these divisions still matter?

- 14:32One of the strength of Solidarity was that it became a symbol for the Polish nation. But wasn’t the narrowly Polish outlook of Solidarity also one of its weaknesses?

Metadata

| Location | ? |

| Date | |

| Length | 15:26 |

Watch and Listen

| Full video (mp4, 15 min) |

| Preview video (mp4, 0 min) |

| Audio track (mp3, 15 min)

|

TranscriptPlease note that this transcript is based on audio tracks and doesn't have to match exactly the video

The influence of the church is growing steadily in Poland over the last decade. Can we have a situation where the defeat of the society brings about also gains for the church?

I do not think so. My personal opinion is that everything which society gains the church gains it also. If the society is defeated it is also a defeat for the church unless you would say that one recovers more quickly than the other one. I mean either society and the church follows suit or the other way round. They should not go backs so to say parallel. Normally, the defeat for one is the defeat for the other.

But you wouldn’t consider for instance that there was an element of compensation for the crushing of Solidarity in making new concessions or trying to seek a new modus vivendi with the hierarchy of the catholic church?

Psychologically perhaps yes. For the people who have lost on every other front this front was becoming more important than any other. But is that a gain for the church? I do not think so. This may be temporary or a kind of ersatz gain but in fact the situation of the church in society is dependent on the extent to which human rights are being respected in that society. And I mean the rights of the church and its gains are totally dependent on the situation of society as a whole. And I think the church has begun to understand that better and better after the war in our country. And the Pope has several times stressed the point that the church has to fight not primarily for its own rights but for the rights of society as a whole and it is a part of this society although transcending it form the religious point of view. This is what I would say about gains.

For forty years Polish intellectuals have tried to become independent form the state. How independent are they really from the catholic church?

I think that many intellectuals have since the beginning been very independent from the church because if you take intellectual life in Poland before the second world war many intellectuals were quite distant form the church and it was an illusion to imagine that suddenly intellectual life in Poland was divided along two… belonged to two different camps: the communist one and the catholic one. The situation was never so, although there was a kind of obligation to choose a front because such was the political situation, the tactical situation, the material situation and so on, and so forth. But I think that many intellectuals kept their own opinion, belong to different philosophical schools also, weather existential or phenomenological or whatever, something different. There were liberals who wouldn’t be, certainly not communist and who wouldn’t be catholic either, not necessarily. The great change which occurred throughout the post-war years was that those who chose finally to associate with let us say communism willy-nilly very often passed towards…

(…)

Would you put the question again? Or no?

Yes. Again. For forty years Polish intellectuals have tried to gain independence from the state, from powers that be, from the Marxist ideology that the state tried to impose. Today Marxism seems bankrupt, the powers that be have no ideological influence. On the contrary, the power of the church has grown. Isn’t there a danger that the intellectuals will fall into that second trap, that they will become now dependent on the church and its ideology.

So what you have to keep in mind is first that before the war Polish intellectual life was not at all belonging to or what I mean divided into two different camps: socialist or whatever and catholic on the other side. On the contrary the major part of intellectuals in Poland was in neutral grounds so to say and had a leaning towards one or the other but not necessarily belonging or giving allegiance to one or the other. Now after the war, for reasons of expediency so to say, or also for some (I think false) hopes as far as the future was concerned, many intellectuals gave their allegiance to the party line, let us say. And polarisation was very strong so other ones had to become more clear as Catholics - but this division was to a very great extent artificial, has to a great extent disappeared now. And they found themselves again in what I called neutral territory, which is not neutral but means simply that they do not belong to either of the two camps. Now what is important simply is that there was a lot of ‘mefiant’, of suspiciousness towards the church on the part of those intellectuals who considered themselves more or less left, on the left. And Catholics felt a bit in the entrenched kind of camp. This has disappeared. I mean: there is much more respect for religion, for the church, for Christianity as such among intellectuals who are not necessarily Christians.

Are there any left intellectuals today in an entrenched camp?

Oh, this I wouldn’t say. I mean I don’t think the party has any intellectuals left really of which one could seriously speak, because the ones that existed have left it more or less. I mean they are either abroad or considered as dissidents. The other ones have much more sympathy and much more understanding for religion than they ever had but that does not mean at all that they chose the church camp and that they are directly dependent on the church. That would be completely false. I mean, they may write in a weekly like Tygodnik Powszechny which is a Catholic weekly not directly dependent on the church. They could even show more understanding for religious problems. I think this is phenomenon that occurs all over the world in fact. I mean that religion is today looked at with more attention and more understanding than let us say before the Second World War or especially in the XIX century. Anthropology has evolved that way and methodology of human sciences has evolved that way. It’s make people more accessible to a way of reasoning which would be considered irrational and so on in the XIX century.

But let me bring that West think that there is a decline of religious belief in the West, in the secularized West. Whereas on the contrary there is a religious fervour in the lands where communism is in rule.

I do not know what you mean by religious belief? Because if you look at the numbers for instance students of theology in the United States. Six hundred per year I think enlisting in different theological departments. That does not mean at all that they want to serve directly the church or become ministers of one Christian denomination or another. But there is this interest which is I think growing. And in Poland in a sense among intellectuals the same phenomenon can be observed.

But in the masses it is different. You say intellectual has to remain independent form the state and from the church. But the political situation is still very polarised.

Yes, yes, certainly.

But for the mass of people - especially after the defeat of Solidarity - you had to choose your camp.

I would say that due to the loyalty of the masses the church is a very strong political factor even if it does not want to play directly in politics. But it has to very often and in any case it weights in the balance. Now of course I think that the one of the great values of Solidarity was that it took the weight of political responsibility form the church to itself so to say. That society had in the long last a genuine political representation which was not the church. This for the church was the very great advantage and therefore the defeat of Solidarity was in this sense also the defeat of the church. That again it had to take the burden of some political representation of society by and large on its own shoulders.

Yes, but at the same time the church made gains as an institution. There is constantly this dual role of a church as a spokesman for society and a church as a religious institution in the proper sense of the word.

Yes, but are there real gains for the religious institution to have a more important political role to play? Willy-nilly? I don’t think so. I think that real gain for a religious institution is to be able freely work in the field of religion and of morals and of intellectual life and whatever. Now as it has to play a role in politics either indirectly or it is involved in politics against its own major aims and, and, and ideas.

Now Cardinal Wyszynski once said that Polish church is closely watched by the security organs but that it is also closely watched by Polish society. That is therefore this constant tension of the church between state and society. How has this dilemma been resolved in the post-Solidarity era?

He said that because the church was the only institution which existed to the very large extent independently of the communist institutions, of the institutions of the state. Now in the post-Solidarity era one has perhaps a tendency to revert to that situation because an institution like Solidarity, or like Independent Writers Union, the Writers Union, the Pen Club, The Painters Union, and so on and so force, which also represented an important fraction, even if numerically small, but important as far as weight was concerned, an important fraction of society – didn’t exist anymore. And therefore again it all fall upon the church to be watched closely by the party on the one side and by the society on the other one. But this is a role that society should get rid of as soon as possible. I mean as soon as an independent political life, pluralistic life where different institutions representing the people by and large, to put it very bluntly, would again be able to exist – at that moment the church can get rid of its political functions.

What has happened to the influence of the party among the intellectuals?

It very much depends on what you call its influence. There were people who represented directly the ideology of party, like Kołakowski at a given moment and he is abroad as you know. He has written a book about Marxism which is sharply critical of its latest developments and you couldn’t call him anymore Marxist today. So there are dissidents, and now there are also people who had a leaning perhaps towards the party, like the great filmmaker Wajda who now had lost that kind of interest and simply keeps together with public opinion by and large, if I may say so. There is a large stream - because there are many streams in Polish intellectual life – but there is a large stream of consensus and Wajda is right in the middle of it, so to say, to judge the past and to look towards the future.

What was a reason for that split between the party and its intellectuals?

Experience, experience which taught us that not much was achieved form what was promised and that this is not a line which leads indeed towards the future which we expected to be able to create for our country and for the world perhaps.

Do these divisions between those who used to be communist and those that are closer to the church, do these divisions still matter?

No, the divisions were perhaps never quite as sharp as one imagines in the West but today and since quite long in fact divisions run not at all parallel to the divisions between communists or Catholics or such things. The main dividing line I would say is between those who are, have some kind of sympathy for a strong or even totalitarian trend within the government and its methods and programmes and those who are leaning towards liberalism, pluralism, freedom. And on both sides you have ex-party members and ex-Catholics as well and these reversals of the alliances is a very typical phenomenon of the post-war years.

One of the strength of Solidarity was that it became a symbol for the Polish nation. But wasn’t the narrowly Polish outlook of Solidarity also one of its weaknesses?

I think that obviously existed that danger but I think that Solidarity has learned from its own mistakes and if it had a tendency to become parochial – the fact itself of recognising that it made mistakes – makes it less parochial. By the sheer fact of seeing that it was not in every respect the ideal which some people tended to imagine it was.

Jacek Woźniakowski (1920–2012)

Jacek Woźniakowski (1920 - 2012) is a Polish art historian, journalist, writer, publisher, curator, translator of literature, a social and political activist, soldier during World War II in Polish Home Army, one of the leading figures in the Polish intellectual opposition against the totalitarian communist power, professor of Lublin Catholic University, founder and editor-in-chief of Znak publishing house, the first Mayor of the City of Krakow in the years 1990 - 1991. He lectured in Poland and in France. As a member of Lech Wałęsa Citizens’ Committee and participant of Round Table Talks in 1989 he played an important part in Poland's successful transition from communism into a free market liberal democracy. He received many Polish and French prizes, honours and awards.