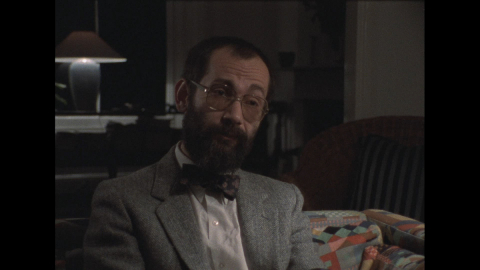

Miklós Tamás Gáspár, 12. 11. 1987, Budapest, Hungary

Questions to the narrator

- 00:10What is the role of dissidents in East European societies?

- 02:18So you are channels of information and debate, rather than a unified political opposition?

- 03:03Could you describe some aspects of the party's militarization of society in Hungary today?

- 04:56Is there any life left in Marxist- Leninism ideology inside the Hungarian Party today?

- 05:53To what extent does the party still use harassment and coercion, like secret police raids and so on in Hungary today?

- 06:39Does the Party still use harassment and coercion?

- 07:28What has communism, now that the ideology's dead, what has communism left behind in Central Europe, in countries like Hungary?

- 10:23How does someone, and what kind of people now, become party officials, full time party activists? What is this process?

- 11:57What are the elements, main elements left behind by communism?

Metadata

| Location | Budapest, Hungary |

| Date | 12. 11. 1987 |

| Length | 13:02 |

Watch and Listen

| Full video (mp4, 13 min) |

| Preview video (mp4, 0 min) |

| Audio track (mp3, 12 min)

|

TranscriptPlease note that this transcript is based on audio tracks and doesn't have to match exactly the video

What is the role of dissidents in East European societies?

I think that the role of dissidents in the different East European countries is rather parochial, and peculiar to the respective country and I don't think that we can really compare the Hungarian dissidents, say to the Polish ones. First, because it is much less important, and second because it's different indeed. So, well generally one would suppose that the dissidents are the most radical elements in, in a political scene in an East European country. And it's generally so, they are the most outspoken and they are the only ones who are overtly criticizing or even politically attacking the system. This is true of us as well, but I think we are playing a very peculiar role which perhaps should be explained a bit. I am alluding to the fact that because we are the only ones who, who speak openly and sometimes loudly about contentious political matters, we are used and we are glad to be used by different political groups to voice their opinions. And sometimes political debates between otherwise well-established and quite official groups representing tendencies of opinion are taking place through us and, and the views of some reformist groups which are quite within the official framework of the system are appearing in the underground press we are publishing.

So you are channels of information and debate, rather than a unified political opposition?

Yes, this is the most conspicuous role, I think and the most important role in the present we are playing, and I won’t characterize our group as a political movement, we are too small for it and too peculiar for that. And well, this might change one day. But for the moment, I think that we are like an information channel for people otherwise unable to confront their views in a finally, still dictatorial system.

Could you describe some aspects of the party's militarization of society in Hungary today?

Well if we are taking the term of the militarization of the society through the party, a term of something which is surprisingly and, and only in the last time happening, it would be false. But there is all the same an invisible and increasingly important phenomenon of some, well militant young groups of people who are not any more the traditional way indoctrinated through the by now quite obsolete ideology of the party, but they are attracted by the militancy and military glamour of some, some associations and organizations like the Hungarian Alliance for the Defense of the Homeland, like the Young Guard, like the Guard of the Young Pioneers and similar organizations, where supporting and other facilities and the military supports are offered for these young people and they find some identity in these rather apolitical groups whose…, the ideology of which is nothing else than some sort of crude nationalism and with of yobbish rudeness and, and well nastiness which sometimes appear quite frightening.

Is there any life left in Marxist- Leninism ideology inside the Hungarian Party today?

TAMAS: Well, if we are speaking of whether there is any life left in the Marxist-Leninist ideology within the party, first we should ponder whether there is still such a thing as the Party. As an organization. We know the Party as the super-government, we know the Party as a body of public administration above any sort of control. But alive, not only the ideological one, of the party cells etc. is dried up, it doesn't exist anymore, it has become completely formal, and the few faithful who still remain are complaining of that quite loudly sometimes.

To what extent does the party still use harassment and coercion, like secret police raids and so on in Hungary today?

I think to a rather large extent, but not in the clumsy and brutal and silly way our neighbours are using it. What I know of course best is the police harassment of my closest friends, my fellow dissidents. Which is a very selective well-targeted activity and where some groups are spared, some personalities like myself are largely spared of the crudest forms of harassment. For different reasons.

Does the Party still use harassment and coercion?

Well the Party still uses harassment and coercion and intimidation against dissidents and similar turbulent elements. But selectively, which means for the most nowadays that they are sparing the so-called well-known representatives of dissident thinking but clamping down quite hard on activists and militants and those people who do the daily work of producing samizdat and producing what after all it's our work to provide information.

What has communism, now that the ideology's dead, what has communism left behind in Central Europe, in countries like Hungary?

Well to assess what communism has left behind in Hungary and what remains still of Marxism and Leninism and of the whole set of beliefs connected to it. It's quite difficult because on the surface I must say that Marxism Leninism is quite forgotten, it's not only on retreat, on the vain, on the defensive, but it’s hard to find it all. Still. I don’t think that it hasn’t left very deep marks on our political thinking and our attitude towards very important number of social issues and, and problems of our daily lives even. What I find slightly disturbing, is that communism finally seems to have reinforced those aspects of our political tradition which existed before and which were always characterized to a very important extent by a resistance to liberal values, to, to a resistance to rational argument about political issues, to a reasonable debate about what is permissible and what’s not. And you know, this kind of political romanticism which always characterized our part of the world is curiously blended with something which is after all to be found in Marxism, because Marx himself was a romantic enemy of the modern age. And this part of his teachings or this part of the halo of Marxism still remains with us. And makes it very difficult to people like myself holding convictions which are largely seen as Westernizing, international, too cerebral, too cool in a way. Because for us traditionally politics is a matter of passion.

How does someone, and what kind of people now, become party officials, full time party activists? What is this process?

Well, I think that the method of appointing party officials and to refresh the party elite, is still characterized by the same principle, the principle of cooptation, so well, officials are not elected as you know, and they are hand-picked by the top but…, and then they might be sent to a training course, they are encouraged to make evening courses in a university and they will undergo a very careful vetting. But these people are indeed a very different type from the manager, which is to be found in the state bureaucracy, different from the old ideologically motivated party activist, these people are just mere and pure bureaucrats and realizing to perfection the idea of the bureaucrat which existed before only in the mind of Max Weber.

What are the elements, main elements left behind by communism?

The main elements left behind communism are after all elements which are not peculiar to communism itself. They are elements of our tradition reinforced by it and which don't pertain to the main body of Marxist teachings. They are anti-liberalism, a resistance towards rational debate in politics, a resistance towards moralizing in politics and a resistance towards reasonable bargaining and a cool approach, because for us politics is first a matter of passion.

Miklós Tamás Gáspár (1948)

Miklós Tamás Gáspár, Hungarian philosopher, political commentator / public intellectual, was born on 28 November 1948 in Kolozsvár (today Cluj-Napoca). He married twice and had four children. His father, Tamás Gáspár, was a Transylvanian-born Hungarian writer, journalist, co-worker and editor of several Transylvanian newspapers.

Miklós Tamás Gáspár studied philosophy at Babeş-Bolyai University of Cluj-Napoca from where he graduated in 1972. He worked as a journalist for a literary newspaper until 1978, when he was banned from publishing due to his political views and undergone harassment by the Romanian secret police for a long time. Due to deteriorating living conditions, he moved to Hungary. Until 1980, he taught at the Department of Philosophy of the Faculty of Arts of Eötvös Loránd University as a research associate, but because of his engagement in politics, he was dismissed and banned from publishing. He was deported from Romania in 1981. In the following years, he was a visiting professor at Yale University and then he worked at English and French universities. From 1989, he was an associate professor at the Department of Philosophy of the Faculty of Law of Eötvös Loránd University, and later became senior staff member of the Institute of Philosophy of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, from where he was dismissed in 2011. Since 2007, he has been a visiting professor of Central European University (CEU).

During the Kádár era in the 1980s, he was one of the best-known representatives of the democratic opposition in Hungary. In 1985, he attended the Monor Meeting, an assembly organized by several widely different opposition groups operating during the Kádár regime. In 1989, he got admitted to the party state parliament as a candidate for the Alliance of Free Democrats (SZDSZ), replacing Péter Várkonyi, who was removed from office and resigned. From 1988 to 1990, he fulfilled the role of deputy leader of the SZDSZ, between 1992 and 1994 he was the chairman of the party’s National Council. From 1990 to 1994, he was a member of parliament. He left the SZDSZ in 2000, but did not abandon politics. Since 2002, he has been the vice president of ATTAC Hungary. In 2008, he was one of the founders of the Social Charter. In 2009, he was appointed as the Green Left Party’s candidate for the European Parliament and held the presidency from May 2010 until the party’s dissolution.

In 1995, he received the Open Society Foundations’ creative award. In 2005, he was awarded the Commander’s Cross (civil division) of the Hungarian Order of Merit in recognition of his outstanding academic and educational achievements and activities in journalism and politics. On 23 October 2009, he received the Twenty-Year-Old Republic Award.

Nowadays, his is an active political thinker and publicist, his thoughts and strong opinions can be regularly read both online and in print media.