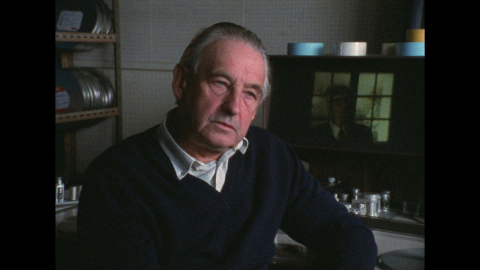

Andrzej Wajda, 20. 5. 1988, Paris, France

Questions to the narrator

- 00:09How do you see the role of Cinema in Central Europe?

- 01:53Isn’t there a danger there that everything becomes politicised? That art, that culture becomes necessarily politicised?

- 02:36To what extent does the fact that the state controls the funding of the film industry influence also its control over the films made?

- 06:21Did you ever have to battle with a censor?

- 09:23So what made the Man of Marble possible? Was it because of Solidarity, was it because the party leadership felt it had to allow such a film?

- 10:36In 1981 you went to Ursus, to the factory and showed the film “Man of Iron”. And on that occasion you said that the role of the artist is to influence society. What did you mean by that?

- 12:18Did the workers recognise themselves in the film when they saw the Man of Iron? Did they see it as the truthful portrayal?

- 13:52Would you say that the role of the artist, the intellectual in Central Europe is to be a conscience of its nation?

- 15:47Would you say that general pluralism of Polish culture today is possible simply because the party has admitted failure of its ideological claim?

- 16:25Would you say that there would be now in Poland the independent culture without a church?

- 18:38If I could go back in history a little bit. What was the appeal of communist ideology for people of your generation at the end of the war.

- 20:26What was for you then the goal of real socialism, what did it mean for you as an artist?

- 20:48What was the aim of socialist realism as an art form?

- 23:21How did you break away from that pattern? What made you break away from that realistic mould?

- 24:48Does socialist realism present the world and people how they should be according to ideology and not as things and people are, so it is not realism?

- 25:37Can I ask a question about how the Polish cinema interacted with developments in other countries, in Hungary or in Czechoslovakia? For instance did Polish film directors after 1956, were they influenced by a Czechoslovak new wave of the 1960ties?

- 27:06So you saw yourself as part of European cinema as the whole?

- 29:03Second question. The lasting impact. What do you think the lasting impact of communism would be on cultural life in Poland?

Metadata

| Location | Paris, France |

| Date | 20. 5. 1988 |

| Length | 33:09 |

Watch and Listen

| Full video (mp4, 33 min) |

| Preview video (mp4, 2 min) |

| Audio track (mp3, 32 min)

|

TranscriptPlease note that this transcript is based on audio tracks and doesn't have to match exactly the video

How do you see the role of Cinema in Central Europe?

First of all we have to answer the question why political films are so attractive to the audience in socialist countries. What the audience is looking for in those films, what they want to see there. In my opinion it is so because the political life is kept secret and the films reveal to the certain extent the direction of the course of events, they reveal what would be, what would happen and our life depends on that. It means they show what the censorship is more sensitive to at the moment and what it allows to show. For example, at the moment when my film, „Ashes and Diamonds” was presented, people belonging to or having family links to Home Army (AK), were informed that, first of all that they might be released from prisons, secondly, they would not be imprisoned again, thirdly, they might have a chance of employment, and four - that there is a chance that they would not be persecuted.

When I made a film „Man of Marble” about the fifties, people who watched it thought that it was a sign that people responsible for the Stalinist past would be somehow punished. So the audience does not come to the cinema just to see the film, they come to see where the authorities give way, how far they retreat, or how much they want to show something and by showing that they let us know in what direction they will continue with their politics. We depend on that politics, our everyday life depends on it.

Isn’t there a danger there that everything becomes politicised? That art, that culture becomes necessarily politicised?

Not necessarily, many people do not want to create political films. Myself, I have made films like „ The Birch Wood”, „ Maids from Wilko”, like „ Everything for Sale” – films where politics does not play important role. But I must say that for a director who has made a political film just once in his lifetime and felt his audience breath while they sit in the cinema waiting for the answer from his film – the director that once swallowed the bait would not retreat and would continue to make political films till the end of his life.

To what extent does the fact that the state controls the funding of the film industry influence also its control over the films made?

It is a question that may sound strange. Yet, I will answer it in a different way. It is always the case that a film director, no matter whom he takes money from – whether money comes from a private producer or from the bank, or from the public resources – the director takes money but wants to do what he wants to do. The directors are trying to fool Hollywood producers just the same. May be a little bit less because Hollywood producers know film issues better and are controlling the director more successfully than people who control film in the socialist countries. There is one more important point that we have got to understand. Namely, the politics is global and the communist party is a monolith – we know it cannot be true. In the party there are various groups that cannot reveal its existence but they have various views regarding various issues. Now, just imagine that one of such groups would like to let people know about its existence. It is simple, in the situation when a film is about to be screened, they can support its screening or forbid it. If they succeed in pushing the film through… It seems that the film cannot be screened at the moment and yet that political group achieves success in showing the film and the group is cemented together not due to common rural policies or around party control issues but seemingly around the question of that film. But in reality that group has got different political aims and they are just checking how strong politically they are as a group. Although political games in socialist countries are very secretive, very difficult – yet film is considered to be a good pretext to reveal various political forces and I think that political groups are consciously exploiting it. Now the situation is a little bit different, you have asked me about current situation. Now the situation is different because the audience has turned away from the cinema. The core of our audience, the audience that used to watch Polish films and loved them, needed them most – the intelligentsia audience has turned away. After crushing Solidarity, the intelligentsia is the next group that was degraded and pushed out. First of all terrible pauperisation, it is extremely difficult to make money. People stay at home and what is very important people have lost faith that they would understand politics by watching films. After crushing Solidarity Polish cinema audience understands that no film, no literature, no press could possibly change things in political life. The system is beyond repair. The system cannot be improved. That system cannot be changed step by step fighting and gaining more freedom each time. Simply, Polish audience does not want films anymore, they want democratic institutions that would defend their rights. Film is not such an institution.

Did you ever have to battle with a censor?

Censorship is very broad term since the censorship office exists as an office, as an external institution. But there are also our internal censors. I censor myself because I am ashamed of certain things and other things I consider silly. My internal censor depends on my education, on my ideas, on my attitude towards religion and so on. That is the censorship we are not talking about. The institution of censorship is created so as to have as little work to do as possible. The censorship created a general situation in which everything is generally forbidden. For example, we were not allowed for many years in Poland to discuss emigrants. Józef Czapski was completely unknown. We could not discuss Miłosz, we could not discuss our greatest writers because everyone living abroad, in the West, was supposed to be an agent of foreign power and we were supposed to defend socialism and it was forbidden to contact such agents. It took enormous efforts, events, and in fact Solidarity itself to overcome somehow such barriers. But that is a starting point for censorship: to create a situation where any discussion about a film based on - let us say – a novel by Czapski, it was out of question because his name could not be mentioned in our press. His first book was on Soviet camps, he published it here in France in 1946. Majority of the printed copies was bought out from each bookshop in secret so the book became very rare. So you know – we can discuss censorship a lot, but the essential thing is to leave for the censorship office as little to censor as possible. And everything else should be so forbidden that no one would even try to touch it. In my opinion if you want to fight censorship you have to make film that is generally from the beginning not acceptable for censors. “Man of Marble” was such a film, for example. It seemed that censors are letting their scissors fall down helplessly because they looked and said „it never happened”. No one expected such a film to be possible at that time. If a film is conceived like that than even if they cut out something from the film, that film remains a certain phenomenon. Such a film defends itself by being essentially a film.

So what made the Man of Marble possible? Was it because of Solidarity, was it because the party leadership felt it had to allow such a film?

No, „Man of Marble” was filmed much earlier, it was filmed in 1975-76. It was just a moment of aspiring to that. There were groups of people, the minister of culture and art at the time, Józef Tejchma who was very engaged and believed that such a film should be created. There were hopes that the events of the fifties need some spotlight and they should be presented in a film. Also people who played political roles in the fifties, who were starting then to build Nowa Huta, to create youth association ZMP, they were in power in the 1970ties. They wanted a film about them to be filmed. ”Man of Iron” was a completely different story. “Man of Iron” had to be screened because big factories such as Nowa Huta, like Ursus, like Stalowa Wola steelworks were sending telexes to the Ministry of Culture that the film was ready and had to be screened.

In 1981 you went to Ursus, to the factory and showed the film “Man of Iron”. And on that occasion you said that the role of the artist is to influence society. What did you mean by that?

Yes, at the time we were thinking in a different way. To believe in political film role is to believe that communist system is prone to change, is improvable. I think that today in Poland nobody believes that a film, a newspaper, press or art could change anything as far as the system is concerned. I think that today everybody is conscious that we need completely different, organised means of social pressure and Solidarity has shown just that. At that time we started to look for close links to the workers. We thought that workers could be our allies. Although it was strange, because in the communist country from the start the workers should be our allies. But the distance between the workers and art or artists was never greater than in the 1950ties in our country, in the beginning of socialism in our countries. We were looking for that contact. I had to stress that the moment when among 21 demands in the Shipyard we found the workers’ demand related to censorship issues, we realised that they were our real allies. We realised that finally someone stronger would defend our rights and we would not have to wait for the authorities mercy to give more freedom.

Did the workers recognise themselves in the film when they saw the Man of Iron? Did they see it as the truthful portrayal?

I have to answer: yes they did. That film had 3 million people audience in just 3 months so people not only waited for that film but also they identified themselves with it, they wanted to see it. Of course the ending of the film was the greatest problem. In the end a mysterious person was informing the journalist that the agreement might be crossed out because the workers had enforced the agreement on the authorities. Three times I put that scene in and cut it out. Because my friends advised me not to finish that film with such a pessimistic ending. I considered that scene to be very important and I felt that something bad was coming, because we had no means of defense, no defense at all. Solidarity was an institution that I would describe as so childish, so naive and honest and that was most beautiful. Solidarity was not ready to defend itself. If 10 million Poles want something than who they had to defend themselves from? What power could be greater than that? So it seemed worthwhile to include that warning in the film. In the last stage of editing I put that scene into the film and it stayed. So that was the main problem that optimists were not happy and thought that the film should not end on pessimistic note.

Would you say that the role of the artist, the intellectual in Central Europe is to be a conscience of its nation?

Yes, I think that this is very important. I had to stress now when XX century is coming to an end we should look towards the beginning and consider the ideas that accompanied XX century from the beginning. It seemed that one of the outdated ideas was nationalism, that it was bound to vanish. It turned out to be the strongest idea at the end of the XX century – the nationalism of small nations. I had to confirm that small nations would never accept the partition of the world between the Soviet Union and the USA. That division is against our interests. I think that national conscience, the necessity of national identity is expressed especially in films. What would Hungary mean to the world without Hungarian films, what would Lithuania be without Paradzanow films? What Poland would mean without a few films we created? I think that for small nations… what films means for them? First of all the film informs the world that such a country exists. How can we do that by other means? By literature – it would be very difficult to translate it. By other forms of art? We do not always have suitable artist. Film has usually broad distribution. Everybody knows that there are films made in Poland, made in Hungary, therefore we inform the world that we exist, that we are alive. Inside each country Poles watch their own films, Hungarians and other nations watch their own films and we are integrating by forming our national identity around those films.

Would you say that general pluralism of Polish culture today is possible simply because the party has admitted failure of its ideological claim?

No, I think that the party would like to unify everything once more if they only could. Two years of Solidarity had enormous influence and created the social resistance. Society has achieved something. I think that this is one of the things the society and specially the opposition fought for and gained for the society.

Would you say that there would be now in Poland the independent culture without a church?

This is the most difficult question generally. The church helped in a very difficult time, three times the church played extraordinary role in Poland. At the time of German occupation when the priests stood on the side of nation and were killed in Auschwitz or were shot like all the other citizens of our country. Immediately after the war when Cardinal Wyszynski decided to say that Poland had its own moral identity, that Poland as a catholic country was different. And for the third time the church stood up for Solidarity. From the beginning of martial law the artists who looked for a protection were gathering around the church. And it had to be said, the church gave that protection to the artists in a way. But the church did not go further. There were Christian Culture Weeks, there were meetings. They built a 1000 churches, in all those churches there were parochial halls that were the only places in the provincial towns where people could get together. But the church did not decide and it would seem unlikely at the time for the church to become the leader of art in Poland, the leader in theatre, in film. I had tried that in the play „Wieczernik” by Ernest Bryll and I had to admit that it was not possible to repeat that experience, it was no longer possible. Because the actors who play in the church performance had to be sure that if they were expelled from the state own theatre someone would stand up for them, someone would provide for them. The church does not want to take on such responsibilities and moreover the church believes that its other duties are more important and culture is just a fraction of the church activities in Poland.

If I could go back in history a little bit. What was the appeal of communist ideology for people of your generation at the end of the war.

That is true that everybody thinks so and keeps asking questions, how could we be so stupid not to be able to distinguish white from black. Yet it was then possible that people like Picasso, Eluard, also not just French but also English greatest writers came to the Intellectuals’ Congress in Wroclaw. All those people could see that there was a certain manipulation going on. It was even possible to know who had used them and no one of them protested. Except just one man who left that Congress in protest. So it was no surprise that we did not see through all that – we were straight after the war, we were deprived of press, we could not listen to the radio. We were totally cut off from the world. We had no idea how the world look like. I had a chance to go and see the West for the first time in 1957. I went to Paris. So first of all our freedom was limited in a way and secondly we were young and very eager to act. And without that eagerness the culture in Poland after the war would not be developed with such an enthusiasm. And I think that despite all the mistakes committed by the artists one have to remember that for many of them artists had paid in their later life and their later death, some literally like for example Tadeusz Borowski. I think that the impulse was something natural after the war. That impulse to stress one’s existence, to participate, that our youth had to find expression even in the most difficult times.

What was for you then the goal of real socialism, what did it mean for you as an artist?

Real socialism exists only in the countries under the direct influence of the Soviet Union and in the countries where Soviet troops are located. Only that is called real socialism.

What was the aim of socialist realism as an art form?

That was not so important what I thought about socialist realism. Socialist realism was very precisely defined. It was known what socialist realism was, all the misunderstandings and passions around that were caused (in the beginning before it was clarified) by our understanding of socialist realism as some kind of continuation of Soviet film avant-garde from the 1920ties, Avant-garde of films, visual art, music of the1920ties. So the whole fight between the politicians, the minister of culture and art, all the people who governed cultural policy and the artists was concentrated on making us understand that socialist realism was supposed to reflect what was done under Joseph Stalin rule in the Soviet Union. We should paint as they painted, we should compose music as they composed, we should write as Soviet writers wrote. Poles could not understand it all. It seemed that there had to be an idea behind it, the idea to create art capable to confront the Western art. We were all young and were looking for an idea like that one, we were looking in such a direction. Yet it turned out that what they wanted us to do was just to imitate, to copy, to follow Soviet art. Of course we had to answer what for it was needed, what for they needed socialist realism? The art was supposed to be a part of greater picture and it was meant to create socialist man who was supposed to be different than the previous man, was supposed to have different feelings, different morality, different world view. To form a man who himself independently from people who lead him, would know his limitations and know his place as just a small part in the machine. Someone else would explain that.

How did you break away from that pattern? What made you break away from that realistic mould?

I did not understand the question.

What make him quit? What provoked you to leave such a form?

This is to be seen in the broader picture. A large group of people, of artists was engaged in the socialist realism because they believed that was the future, the avant-garde. Slowly when the background of the affairs was revealed and the truth turned naked, the artists, older than me, first of all, much more experienced, knowing more about art and life started to understand that there was no future there. There were also the events of 1956 and people who animated those events, Polish intellectuals helped us to look critically on the events. So we managed to open our eyes and see early enough.

Isn’t it the case that socialist realism really does not depict reality as it is but rather as it ought to be according to ideology and that once the ideological faith is no longer there…

Sorry I got lost.

Does socialist realism present the world and people how they should be according to ideology and not as things and people are, so it is not realism?

That is, that was one of the general rules. And no. They believed that it was socialist realism because it did not present like Courbet’s realism - poor people as they are. You just see a poor man, but you know that although he looks poorly clothed, yet he lives in a socialist country so he cannot be poorly clothed and he should be painted in nice clothing and in sunshine. Since sun shines always in the socialist country and the grass is always green there. And generally there is an optimism because it might be bad now but it is all for the better future tomorrow.

Can I ask a question about how the Polish cinema interacted with developments in other countries, in Hungary or in Czechoslovakia? For instance did Polish film directors after 1956, were they influenced by a Czechoslovak new wave of the 1960ties?

We had always watched very closely the films created in our neighbouring countries, as well as Soviet films because we were looking for the signals showing what was going on in our camp, what was about to change. Last events in the Soviet Union when the filmmakers started playing such an important role proved that film was still the pivotal point and something very important. So we had watched that closely. But in the beginning other films were important for Polish filmmakers. Polish Cinema emerged from Italian neorealism. The first films of Zavattini, the first films of de Sicca, the first films of Rossellini - we greeted them with joy in our hearts. That was the freedom from which Polish film started to grow. I was then making my first film „Generation” in 1954-1955 and the traces of that influence are visible in that film for sure.

So you saw yourself as part of European cinema as the whole

Yes. I think that Polish Cinema has always watched very closely what was going on in the world and we have never allowed to be pushed away from Europe. I think that is a suitable description that we have not allowed to be pushed away from Europe. Since Europe has done nothing to keep us close to hold us. Not a long time ago I have received a survey form Brussels to fill in the most interesting films in recent years. I look at the back of the form and it describes that the survey does not include Poland, Hungary, Bulgaria or Czechoslovakia. Because it includes only the economic common wealth, the European Commonwealth, but to such a Europe I do not want to belong at all, such a Europe can live its own life. Europe should understand that Europe reaches much further to the East and they should keep it in their minds every day. Europe does not end at the Berlin Wall. Simply because due to the death of Stalin actions that were planned for Poland were never completed. In Poland there were never completed such a “cleansing” of intelligentsia like in the Soviet Union. In Poland the agriculture remained in private hands so we did not starve. The church in Poland was never destroyed in a way the orthodox church was destroyed in the Soviet Union. So those forces still existed in Poland and occasionally acted. Whenever the economic situation worsened, whenever social climate became hopeless each time those forces would activate and demand. People wanted their rights. The thing is we do not ask for privileges because the privileges are for individuals, but we want rights for all.

Second question. The lasting impact. What do you think the lasting impact of communism would be on cultural life in Poland? Lasting influence. Had the communism a permanent influence on culture, on life in the country?

It is hard to tell. I do not see it in our country. But in the Soviet Union the situation was very different. In the first years the artists there could spread their wings and created beautiful, thrilling works of art. But they did not realise that they were wrong, they did not realise that they were on the wrong path and that the party and the authorities did not expect that from them. That they expect a totally different art. But in Poland, in Poland it would be difficult to say that important works of art were created. We could say that a novel “Ashes and diamonds” was written. There are many people who are against that novel and believe it to be a false book because it shows only one side. Andrzejewski was well aware that there was the other side. What was on the other side? Not all the Polish pre-war politicians perished immediately. In Poland at the same time when Maciek Chełmicki was killed there was a terrible and bloody battle with peasant movement, first of all with the peasant organisation… oh Jesus Christ... [a voice: PSL] …of course. At the same time when Maciek Chełmicki was killed in Poland the authorities destroyed PSL [Polish People Party] in bloody fight. Why it was absent from the novel? At the same time I had to admit that Jerzy Andrzejewski when we started writing our script…

That is true that it is not present in the novel. But at the same time from the beginning of our work on the film “Ashes and diamonds” Jerzy Andrzejewski did his best to put more truth into the film, to offer a deeper insight into the reality then it was in the novel. He did not have to do that, he was a great, famous writer, awarded with all possible awards. I was a film director at the beginning of career. He did it only in the name of truth. I think that the conflict between the society and the authorities stems from the fact that the authorities keep promising a lot. The permanent propaganda in radio, press, television, cinema keeps telling that happiness is very close and will come tomorrow. So there are recurring conflicts and they are deepening because the society expects more and more while it can receive less and less. One of the previous popes, predecessors of our John Paul II, said a very beautiful and deep statement against communism. He said that communism promises more than it can give and therefor ignites hatred between people. I memorised that sentence especially since I read it in the communist party newspaper Trybuna Ludu and I quote it often because I believe that sentence grasps the conflict on the deep level, the conflict that we as Poles feel very deeply.

Andrzej Wajda (1926–2016)

Andrzej Witold Wajda (6 March 1926 – 9 October 2016) - Polish film and theatre director, Oscar laureate (2000), one of the creators of the "Polish Film School". President of Polish Filmmakers Association (1978-83). He supported Solidarity since August 1980 strike. He presented Polish struggle for freedom in films: A Generation (1955), Kanał (1957) and Ashes and Diamonds (1958) and portrayed Solidarity ethos in political trilogy Man of Marble (1976), Man of Iron (1981, Golden Palm in Cannes), Wałęsa. Man of Hope (2013). Member of Lech Wałęsa Citizens’ Committee (1988). In free Poland, he served as Senator (1989-1991), President of Presidential Culture Council. He was elected to Polish (PAU) and French Art Academy. He initiated Film Group X (1972-1983) and opened Wajda Film School in Warsaw. He represented personal, creative, political and innovative cinema. He received top Polish and French honors including Polish Order of the White Eagle and French Legion of Honour. He received all top film awards: an Oscar, the Palme d'Or, Golden Lion and Golden Bear.