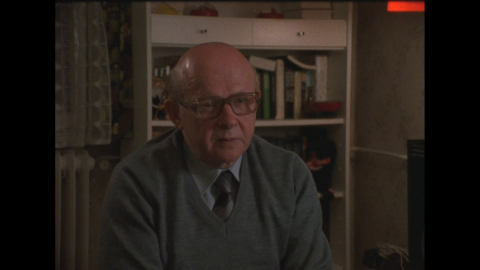

Vladimir Farkas, 16. 10. 1987, Budapest, Hungary

Metadata

| Location | Budapest, Hungary |

| Date | 16. 10. 1987 |

| Length | 05:16 |

Watch and Listen

| Full video (mp4, 5 min) |

| Preview video (mp4, 0 min) |

| Audio track (mp3, 5 min)

|

TranscriptPlease note that this transcript is based on audio tracks and doesn't have to match exactly the video

So, the Soviet interrogation experts led by Belkin lieutenant-general arrive in Budapest and they bring Lazar Brankov with themselves. I do not know whether you know who he was, there is not time to speak about it now, he was and anti-Titoist Yugoslav émigré, who had been arrested in Moscow, but who had worked in Hungary in the embassy, in the Yugoslav Embassy, and they bring the idea of the Rajk show trial. But I do not mean that this phase, that is the classical Rajk case that you know from the records, from the ‘White Book’, from the trial in the Vasas Hall, that this went through during Belkin’s time. I do not what to say that Rákosi does not take part in it, he talks with Belkin every day, he talks more with Belkin than with Gábor Péter, the other member of the. The other members of the political committee, who took part in the case previously, are left out practically and unfortunately, I have to say that although beside each Soviet expert there is a Hungarian investigator, for example with Pál Justus it is me beside a very agreeable major called Kremnov Kamenkovic, but they take over the investigation, that is they do not take part in it as advisers, but they take over the whole investigation. However, the indictment is not made by them, that comes from Rákosi.

Can you tell us about, was it a wise thing to visit Western embassies in the 50s?

Well, look, I did not work at the counter-intelligence but in my opinion, it was just as well not wise to visit Western embassies in Budapest in the 50s as it was not that wise to visit let’s say the Soviet Embassy in London or Washington. That is my opinion. Or let’s say to visit the Chinese Embassy in Budapest in the 60s.

Tell us about the lifestyle of the party elite?

Well, I can tell you something about this because on the on hand, my father was part of the most important leadership, on the other hand, I myself was a leading member of the ÁVH. It is a very interesting thing that Rákosi always presented himself as a puritanical man. Let me tell you a short story. It was said among those surrounding him, that “poor Comrade Rákosi, his shirts are worn out and he has not got enough money to buy new ones, so he has to make new collars from the back of his shirts”. But Rákosi lived, I know his house, in Lóránt Street, in 56, everybody knew it. But in 52, on Zoltán Vas’s initiative they built such a palace for Gerő, Farkas, Révai that Rákosi’s house in Lóránt Street was nothing in comparison. This place was more luxurious and bigger, too. As far as I know, the guesthouses of the government and the party used to be there. And they were furnished with enormous luxury. Now, the so-called nomenclature, to use a Soviet phrase, I mean the people in leading positions, to which I belonged at the ÁVH, they had benefits, not in their salaries, but in Hungary there were exclusive shops, a chain of shops, which existed even in the Soviet Union before Gorbachev, where you could get goods, food, clothes, shoes that a working man could not buy. So there were these kinds of benefits, and as far as I know, the MSZMP (Hungarian Socialist Worker Party) stopped them after 56.

What sort of people were in the physical force department? Were they Nazis?

I know only those of them who worked in the ÁVH centre. One of the most well-known names among them was Gyula Princz. I know he was a member of the Hungarian anti-fascist resistance, armed resistance. Another such person, who was Gábor Péter’s so-called security officer, who distributed for years the literature of the Hungarian underground communists during the fiercest terror, that is he risked his life from day to day. I have mentioned these two examples to show that Stalinism and the Rákosi regime made from those men who joined the anti-fascist fight obviously because they followed humanistic aims. And they ended up here.

Vladimir Farkas (1925–2002)

Vladimir Farkas, one of the chief officers of the ÁVH (State Protection Authority) in the 1950s, was born in Kassa (today Košice), then part of Czechoslovakia, on 12 August 1925, and died in Budapest, on 13 September 2002. He received his first name in the memory of Lenin.

He was born into the labour movement, his mother left him at the age of four as she chose to continue illegal activity for the party, while he did not even meet his father, Mihály Farkas, until the age of 14. He was raised by his grandmother, they lived in the lumber cellar of a tenement building in Kassa. In 1939, Zoltán Schönherz, a family friend, helped in sending the young boy to Moscow with fake documents to his father, who was already living with his new family in the infamous Hotel Lux. His father soon regretted his decision, he was reluctant to see his son. Between 1942 and 1943, on behalf of Rákosi, he graduated from the Kushnarenkovo Party School, the Comintern Cadre School, and then took part in a radio training to be sent to Hungary, but this did not occur due to the end of the war.

In the summer of 1945, his father moved to Budapest with his family, and their surname was then Hungarianized from Lőwy to Farkas. In 1946, he was placed to the State Defense Department of the Police and then to the Operational Technical Subdivision, which conducted phone tapping, censorship of mail, and later became its head. Over the years, he reached the rank of lieutenant-colonel, became a confidant of Gábor Péter, and was commissioned to organize the cross-border political reconnaissance of the ÁVH, the Intelligence Department. However, he did not have only technical tasks. From 1949, he also participated as an interrogator in the investigation of almost all fabricated cases: during the investigation of the Rajk case, he was a permanent interrogator of Justus Pál, Györgyi Vándor and others, he was involved in slandering the former social democrats within the party, he led the initial stage of the investigation of the case of János Kádár, Gyula Kállai and others, and was nominally the leader to coordinate Gábor Péter’s former deputy, Ernő Szücs and his brother’s fabricated espionage.

After Stalin’s death, during Imre Nagy’s first term as prime minister, an inspection of the ÁVH’s activities began, with the arrest of former leaders and senior officers. Vladimir Farkas left the ÁVH in 1955, a year later he was prosecuted, Rákosi singled him and his father as scapegoats. He was arrested the day before László Rajk’s reburial, during the 1956 revolution, and was still in prison after that, being only released in 1960.

After prison he worked as an under-clerk, people whispered behind his back, and the Kádár regime did nothing to help him just like many other ÁVH cadres. In the 1980s, he turned to politics again, facing his own misdeeds and that of the system he served. After the regime change, he wrote his memoirs, was happy to give interviews, and openly admitted and took responsibility for his actions. He married three times and had two daughters from his first marriage.