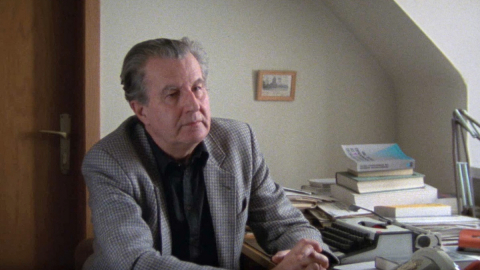

Zdeněk Mlynář, 1. 1. 1988, Vienna, Austria

Questions to the narrator

- 00:14In 1948 the Communist Party was the strongest party in Czechoslovakia, attracting many intellectuals and young people. There was a remarkable element of idealism and enthusiasm there. What are your recollections of that period?

- 01:46As soon as it seized the monopoly on power, however, the party implemented a Stalinist or Soviet model. Was there any other choice, or was this inevitable?

- 03:17But I would also like to ask about your personal recollections, if you have any, of the period after 1948. It is the period of Stalinist terror but also a time of great enthusiasm for the nation.

- 04:25So there was idealism, belief, ideology, but on the other hand there was also the apparatus.

- 04:55What are the main characteristics of the apparatus in the 1950s?

- 06:14The apparatus is thus the continuity of the power system, but how did the role of ideology change? In the 1950s it played a significant role, and still in the 1960s to some extent all changes were conceived within the framework of this ideology. How in yo

- 08:23So the apparatus actually cannot get rid of the ideology, even if individuals working in the apparatus contributed to that?

- 09:29How can factions arise inside such a monolithic power system?

- 10:38This means that economic factions as well as factions related to military or security apparatuses may have their say?

- 12:04And how did this work specifically in Czechoslovakia in the 1960s?

- 13:07And so how can the election of Alexander Dubček be explained then? How can one explain that the reformers suddenly became the majority in the Party leadership and inside the apparatus in 1968?

- 14:14And do you think that it would be possible, if the process hadn’t been forcefully brought to a halt, to continue in the democratisation and pluralisation of society while maintaining the single party system?

- 15:45How did you see the development in society, the pressure from below which grew during the Prague Spring?

- 17:46So you think that there were illusions on both sides? There were illusions in society as regards the potential to transcend this democratisation process, and on the contrary the leadership had illusions on how they could rule or direct this pressure from

- 19:30What specific forms of Soviet pressure were there on the pro-reform process of 1968?

- 20:57Did you all think then in the summer and especially at the negotiations in Čierná, that there was still time and the chance to explain to the Soviet leadership what the point actually was, to assure them somehow or to prevent a potential invasion?

- 23:08In your book you describe the negotiations in Moscow and also mention what Kádár had told Dubček, if he knew with whom he was dealing.

- 23:21Yes. Did the Czechoslovak leaders have an idea to whom they had the honour of speaking?

- 24:43How did the Soviet leaders then expect or judge the development in Czechoslovakia? And why did they consider it a threat? Where did the threat lie?

- 25:22But at those negotiations in Moscow, they did try to explain to you why they considered the development in Czechoslovakia […]?

- 27:45How could you explain that after the invasion the Party was able to re-establish and rebuild the apparatus and maintain it for the next twenty years just the way it did?

- 29:50How do you explain the duality in the history of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia, that on the one hand it is the party which went to the greatest lengths in its attempt to combine the communist system with the principles of democracy that were deepl

- 31:44And how do you think that Gorbachev and his policy could influence the future development of the systems in Eastern Europe?

Metadata

| Location | Vienna, Austria |

| Date | 1. 1. 1988 |

| Length | 35:04 |

Watch and Listen

| Full video (mp4, 35 min) |

| Preview video (mp4, 2 min) |

| Audio track (mp3, 35 min)

|

TranscriptPlease note that this transcript is based on audio tracks and doesn't have to match exactly the video

In 1948 the Communist Party was the strongest party in Czechoslovakia, attracting many intellectuals and young people. There was a remarkable element of idealism and enthusiasm there. What are your recollections of that period?

I joined the party as early as in 1946, which is two years before February 1948 and even before the 1946 elections, in other words in March. It wasn’t yet clear whether the party would be the strongest or not. I’d say I joined it for two reasons, both of which were idealistic in their own way. Firstly, after the war, for us the Soviet Union and the communists represented something which was so radically opposed to Nazism, war and what we had lived through, and we wanted to be part of it. And as our parents’ generation was rather cautious, we were radical enough to want to join the most radical ones. Secondly, I had actually joined the party as a secondary school student also because the Communist Party was then calling for student self-governments. We as students had the opportunity to influence something, it was against bureaucracy, against school authorities and so on. And I’d say that the same personal qualities that then led me to join the Communist Party inevitably later led to my expulsion from the Party in 1970, as I kept persisting but the Party was changing.

As soon as it seized the monopoly on power, however, the party implemented a Stalinist or Soviet model. Was there any other choice, or was this inevitable?

Of course. The Party gradually began to implement the Soviet Stalinist model after 1948. I’d be lying if I said in retrospect that I wasn’t in favour of that model. I thought that this radical model, in which all the enemies of our just belief and ideology would be suppressed, was the right one. In fact, in my own judgement, it didn’t necessarily have to turn out that way. I think that Czechoslovakia had embarked on the path of building its own socialism even before 1948; even the years 1945–1948 were a kind of Czechoslovak road to socialism, but not to the Soviet model. The Party here had good prospects to become the party with the absolute majority in the parliament, but not with a monopoly of power, not to eliminate the opposition and suppress the possibility of it losing the election if the voters didn’t like what it did. That was already a step towards Stalinism, and that’s where it begins, of course. However, everything then was set in the international framework, the Cold War, the issues with the Soviet policy that begins in 1948 around the Marshall Plan, and so on.

But I would also like to ask about your personal recollections, if you have any, of the period after 1948. It is the period of Stalinist terror but also a time of great enthusiasm for the nation.

No, it wasn’t a time of terror for us. We were part of the winning party, we did voluntary work, worked in the mines for free, in the border areas, there was something in it, like with every collectivism. As young communists we did not know the political practice of the Soviet Union, we didn’t even know the theory of the communist party, it was something that thrilled us to be part of a team sharing the same will, the sense of some sort of transpersonal mission, solidarity, the relationships between us inside this sect of communist youth, however absurd it sounds today, were collective, pleasant and human. For the others, of course, we were something absurd and gradually also came to be something dangerous.

So there was idealism, belief, ideology, but on the other hand there was also the apparatus.

Yes, I think so. The apparatus was only just beginning then. I was actually a member of the apparatus of the Youth Union after my GCSEs, and what it looked like was that in each district we had one secretary, one typist, and later two secretaries and one typist, and that was the whole apparatus for a district unit of the Youth Union in 1948. It became more extensive later, in the 1950s.

What are the main characteristics of the apparatus in the 1950s?

In the 1950s the apparatus actually begins to act as the representative of actual absolute power, controlled by no one. And what makes the Party’s apparatus special is that it is in fact built as the control apparatus over all other spheres, over the state, the economy, the army, the judicial system and so on. And it is not in fact a case of the Party’s apparatus deciding everything, but of being one which has the authority to decide anything. So anyone in the party apparatus may correct, adjust or criticise the decision of a finance director, but also that of a judge. And each of the other power, state and economic apparatuses knows this, which predetermines the dependence. Secondly, the party apparatus actually nominates and approves people in official and managerial positions, referred to as the nomenclature, i.e. no one can be appointed to certain positions without the direct approval of the party apparatus. And that’s the second means by which the party apparatus controls the power apparatuses of the whole state, the whole of society, and that’s where the extraordinary power comes from. The apparatus does not answer to anyone, not even in the formal sense as regards voters, unlike, for instance, municipal councils or parliament in a real socialist government. No professional qualification is even required, as de facto it does not control, but merely issues comments and only controls staff appointments. In this sense, it is purely a power apparatus, a purely controlling one, actually designed to enable the small group that makes up the party’s politburo, some 10–12 people, to decide on anything if they want: on laws, on international treaties, the economic plan, the sacking or recruitment of staff, absolutely anything.

The apparatus is thus the continuity of the power system, but how did the role of ideology change? In the 1950s it played a significant role, and still in the 1960s to some extent all changes were conceived within the framework of this ideology. How in your opinion did the role of ideology change in Czechoslovakia over time?

This varies from country to country. I believe that in Czechoslovakia ideology still played an important role in 1968. The pro-reform communist ideology is a kind of logical continuation of the communist ideology from the times before February 1948. It still played a role. Of course the contribution of ideology to real policy is, I’d say, sometimes a small one. Ideology is mostly abused to justify what the power apparatus has done. In fact it often even happens that the apparatus leaders decide on something and then assign the secretary in charge of ideology the task of finding an adequate ideological justification for it. In this respect, however, the contradiction between the ideology or idea which guides a certain movement and the practices the movement engages in when it holds power, is not specific to communism. The same used to happen with the church and with the ideas of Jean-Jacques Rousseau, or the practice of Napoleon for instance, and it would be difficult to compare. In any case, ideology is just a sort of appendage. But in the Soviet system, or in a system of the Soviet type, the role of ideology is still to legitimise the power, and all the steps that the power takes must be, at least on the surface, in line with the certain logic that the ideology prescribes.

So the apparatus actually cannot get rid of the ideology, even if individuals working in the apparatus contributed to that?

I’d say that in the Soviet system, ideology is the only permitted system of opinions and notions in which the ruling group may reflect reality. It is its only arsenal of notions. You cannot argue using notions the ideology disproves of. Or, values are determined by the ideology and you have to argue even in favour of changes by saying yes, the true approach of the ideology means something other than what we have in reality today, so the ideology has been distorted, not that the actual ideology is wrong. This makes it very similar, in typological terms, to theocratic systems.

How can factions arise inside such a monolithic power system?

Exactly because it is so monolithic, factions must occur, as the reality is never uncontradictory. The occurrence of factions actually means that standpoints, other interests and other opinions are reflected that differ from those officially expressed in the seemingly univocally accepted line. And that any minority interests and differences from what is presented as the monolithic line must be expressed inside the party as different opinions of different groups just because there is no other way to express it in institutional terms. That’s the problem, that when there is a ban on the institutional expression of the actually existing pluralism of interests and opinions, pluralism seeks to find a way inside the only institutionally acceptable political system, i.e. including the Communist Party.

This means that economic factions as well as factions related to military or security apparatuses may have their say?

Of course, roughly speaking. The key groups of the power elite are described as social groups, distinguishing the party apparatus, state and economic, the army, police, especially the political police. But I don’t think that one can simply schematise like this. I think that a faction’s attitude is in fact or may be a certain opinion. In reality, something comes to be considered as a faction only when the opinion begins to be promoted by a group which is specially organised for the purpose and has its own rules which differ from those of the party as a whole, that’s what the formal definition says. And that’s what’s forbidden. But when various groups emerge which have an opinion, for instance, that censorship is too strong or that things should be done differently in cultural policy than how they are done now, the members of such a group can be people from the security, party and state apparatus, as well as for instance the economic apparatus. So this is not always identical with the structure of the power elite itself.

And how did this work specifically in Czechoslovakia in the 1960s?

This actually began in the 1950s, after 1956 in fact, in Czechoslovakia, meaning after the de-Stalinisation in Moscow, after Khrushchev’s speech at the 20th Convention of the Soviet Communist Party. The Czechoslovak leadership were trying not to change policy too much officially, as they were linked to the Stalinist trials which had taken place four years earlier in 1952, and therefore many various groups, opinion streams and trends occurred inside the Party which could not be voiced officially. And they were in fact preparatory streams which, twelve years later, in 1968, resulted in the programme known as the Prague Spring, where democratisation meant the freedom of expression of various opinions and the freedom to be organised in various interest groups.

And so how can the election of Alexander Dubček be explained then? How can one explain that the reformers suddenly became the majority in the Party leadership and inside the apparatus in 1968?

I think that the election of Alexander Dubček or the year 1968 was the very last step, that the process of the differentiation and creation of various opinions, usually opposing the official policy, took years inside the party as a whole as well as in society; it took twelve years from 1956. And when it made its way to the Party’s Central Committee and the leadership admitted: “Yes, this can no longer go on, things must be done in another way …”, this actually ended the differentiation process and the new political line became openly manifested as the political line of the Party’s Action Programme where one of the rudimentary ideas is that pluralism exists and cannot be suppressed. Another question is what institutional forms the interests of plurality should take on. In 1968, for instance, we were afraid that if they took on the form of various political parties in the beginning, the totalitarian system would not be reformed but would erupt, it would be dismantled and destroyed, and that it would be dangerous and fail. So the issue of not allowing political parties other than those which formed part of the National Front was conceived in such an inverse manner. But otherwise an array of possibilities was to be provided, from freedom of the press, speech and gathering to institutionalising such social interests which had previously been suppressed.

And do you think that it would be possible, if the process hadn’t been forcefully brought to a halt, to continue in the democratisation and pluralisation of society while maintaining the single party system?

It was probably possible for a certain time. The thought then was that a transitional system would be in place for several years and would conclude by adopting a new constitution, and this would show in practice how the other mechanisms to express various opinions work. I think that it was possible just because on the one hand, people still had an idea what democratic life meant from before 1948, and on the other hand they had a realistic enough idea that Czechoslovakia cannot act as if it lived in another planet. This means that it has to reflect on what is or is not permissible from the viewpoint of the Soviet Union and its ideology, that compromise is necessary, just like the Hungarians were able to realise that there are certain limits to the reforms. Unfortunately, however, our Czechoslovak ideas of what Brezhnev’s Soviet Union was able to tolerate were very wrong, as we had assumed that it would tolerate such an attempt, too, and that was something the Soviet leadership never intended to do.

How did you see the development in society, the pressure from below which grew during the Prague Spring?

It varied a lot. In general, as a man with political responsibility for a certain section I saw something positive in the pressure from below. On the other hand, I was afraid, and I still think that it was justified, that if the pressure is manifested in just one form, such as freedom of the press, it is not enough, as it can’t work normally and fulfil the role it has in a normal democratic society. For the pressure from below to become the real driving force of democracy, there must be several different institutionalised tools, meaning elections, various organisations, various relationships between them, inside these institutions, democracy and elections, the relationship between the minority and majority, respected inside these elected bodies, plus freedom of the press. And all of this together may gradually, in a process rife with contradictions, show only after a certain time what the majority actually wishes to do or not. But the trouble in Czechoslovakia was that the only thing that worked was that there really was freedom of the press without censorship. And the people thought that because they were free to say almost anything and could talk about anything, their freedom and democracy was already guaranteed, but in fact that was just an illusion. I have always tried to draw their attention to the fact that it takes some time and that without other institutionalised guarantees, freedom of speech cannot be unilaterally applied. I was and still am a supporter of the idea that the state should apply censorship in some cases, especially with things that were not in our favour in terms of foreign policy.

So you think that there were illusions on both sides? There were illusions in society as regards the potential to transcend this democratisation process, and on the contrary the leadership had illusions on how they could rule or direct this pressure from below.

You could say that. There were other illusions, too, basically three. The illusion of the Party’s leadership over its own capacity within the framework of the Soviet Bloc was, I think, the first illusion. The idea here was “Say yes to the reform, but no to the breach with the Soviet Union, like Yugoslavia did, at any price; that must never happen”. Under such circumstances, you could only make do with what would be approved by the majority of the leaderships at the time, in other words roughly what Kádár did in Hungary, and then all that should have never begun. Illusion number two was the idea held by the Communist Party’s leaders that the enormous support showed by the people at the beginning, because it had opened up the path to democracy after twenty years of totalitarian dictatorship, would in itself last and that people would only want whatever the leaders decide to do. And the third illusion was that of the people who thought that the leadership may, as it were, cross the certain limits it had, and it would depend solely on how hard we push from below, how radically we manifest ourselves, and that it could take a long time, although in fact those few months of the Prague Spring were only provisional as regards the state of the political system.

What specific forms of Soviet pressure were there on the pro-reform process of 1968?

The pressure basically came in three different forms. There were ideological and political objections and notices that our policy deviated from the generally binding standards and laws of the building up of socialism, as they officially put it. Secondly, there was the threat of economic pressure and a certain unwillingness to assist in the economy as long as we do what we want in terms of policy. And the third was the military threat which arose as a possibility in May, and through the manoeuvres in June it developed into an armed intervention. The mistake the Czechoslovak leadership made was that although they were actually aware of it, it helped to keep the whole issue secret, in the hope that the Soviet leaders would not resort to military intervention unless Czechoslovakia were to do something that would mean leaving the Warsaw Pact or threatening the foreign policy interests of the Soviet Union. And Dubček’s leadership obviously did not want to do that. Whereas the Soviet leadership still resorted to that, and eventually Czechoslovakia was left isolated and unprepared for such a form of intervention.

Did you all think then in the summer and especially at the negotiations in Čierná, that there was still time and the chance to explain to the Soviet leadership what the point actually was, to assure them somehow or to prevent a potential invasion?

Speaking for myself, I didn’t think that it would be possible to explain anything; it was clear where the differences and conflicts lay. I was personally rather afraid that harsh intervention would come at the very beginning. I also spoke about that at the plenary session of the Central Committee in April, and that’s the sentence in my speech which was then censored in the Party’s national daily. I said that if the situation were to continue like it had before April, the leadership would no longer have control over the development of the political spectrum in the country and that that’s what their task was, otherwise there would be the threat of something similar to what happened in Hungary in 1956. And this was censored in the newspaper because it was too pessimistic. But I later rather abandoned that opinion because in the summer, in July and August, I really thought it wouldn’t happen, not because we had convinced the Soviet leaders that the Prague Spring was right, but because they understood that internal problems would arise after the Party’s convention to be held in September. The Czechoslovak leaders would have to suppress many things which were extreme from the viewpoint of the reform from above, get rid of them, they would find themselves in difficulties and would simply have to turn against the radical pro-reform wing. But that would mean that Moscow would agree with the reformists eventually coming to power in Czechoslovakia, i.e. pro-reform centrists, and that’s something they did not want to happen. They would really prefer the conservative views of those who were fully against the reform process such as an action programme.

In your book you describe the negotiations in Moscow and also mention what Kádár had told Dubček, if he knew with whom he was dealing.

To whom he had the honour of speaking?

Yes. Did the Czechoslovak leaders have an idea to whom they had the honour of speaking?

I wasn’t there when Kádár said that. It was said when Dubček was meeting Kádár in Komarno. I only later heard that Kádár had said there, “Don’t you know to whom you have the honour of speaking?” He said that when he had found no way to explain that to Dubček. I don’t think their ideas were completely unreal. Dubček himself had lived in the Soviet Union for seventeen years, he knew it there, he was familiar with the apparatuses. But there was the idea that there was no reason for intervention even from the Soviet point of view, that it would have so many adverse consequences for the Soviet Union that the benefits would never outweigh them. So our theories as to what happened in Moscow after Khrushchev had been overthrown were quite wrong. We had in fact wrongly estimated the policy which was already anti-Khrushchev and neo-Stalinist in 1968, as it slowly comes to be criticised now by Gorbachev’s leadership as a dead-end policy, which focuses on the stagnation inside and militarism and the demonstration of military force on the outside. That’s where our estimates were wrong then.

How did the Soviet leaders then expect or judge the development in Czechoslovakia? And why did they consider it a threat? Where did the threat lie?

This is hard to answer because nowhere in the documents, if they exist, can you find a reasonable answer, or one adequate to the intervention. There are many clichés on the role of the party being weakened, the West German revanchists threatening to intervene, the threat of leaving the Warsaw Pact, but they are all nonsense.

But at those negotiations in Moscow, they did try to explain to you why they considered the development in Czechoslovakia […]?

No, there were no explanations given there. I wrote about it in my book of memoirs. Brezhnev put it very simply, it was his patriarchal idea that World War Two means that wherever a Soviet soldier set foot, there our borders are shared, including the Soviet Union. And we must respect and do what the Soviet leaders wish. And it was strange to him that we could not understand such a simple thing, that for him a notion such as the sovereignty of a Soviet Bloc state was merely a propagandist’s phrase, but not the real possibility that the state could make trouble in that it was not abandoning the Warsaw Pact, but in its internal policy it was doing something that seemed to him impossible, dangerous and bad. Probably there really was something in it that cannot be seen as bad will, but a total difference in conditions. I think that for instance the then Soviet leaders were unable to understand how any communist party could rule with a system other than theirs. We, on the contrary, had the experience from before February 1948, and knew that it was possible. It would inevitably mean that the party would sometimes become a minority, must form a coalition with another party, must change its policy according to how the people approve it, but that does not mean the white terror here and communists being hanged out in the streets, like they kept threatening us with. Actually the mindset of the people, and this applied to Gomulka and Ulbricht as well, from countries where the communist regime was able to maintain power only due to the presence of the Soviet army there, made them unable to understand us, because we did not have the Soviet army here. They came in May 1945, left in December 1945 and did not come again until August 1968, so we did not have the mindset of the politicians who depended on their regime being backed by a foreign army in their country. We thought it didn’t have to, and they thought it couldn’t be done any other way.

How could you explain that after the invasion the Party was able to re-establish and rebuild the apparatus and maintain it for the next twenty years just the way it did?

I think that the KSC was able to do this only at the price of destroying the party it represented in 1968 and earlier. The expulsion, expelling of approximately one-third of its membership in numbers, that means more than half of its active members, of which probably almost 80% were those who had joined the Party just before February 1948, in fact meant that they got rid of those people and made the Party an appendage to the power apparatus, and thus “normalised” the circumstances. There is some sense in that word, as the circumstances really became similar to what was normal in countries where communist parties were never majority parties, never got the majority of the vote in the election, and grew up on the support from the Soviet army, and were actually representatives of the power apparatus. In Romania, at the time the Soviet army arrived, there were merely a thousand members of the communist party, and in 1947 there were seven hundred thousand. But here the Party still had 40% of the election vote in 1946, without the presence of the Soviet army and in competition with other political parties, so the circumstances are incomparable. So there was room to normalise, strengthen or, as you say, renew simply because the party that had been there before was destroyed and a new party was built, more similar to those that exist in the surrounding Soviet Bloc countries.

How do you explain the duality in the history of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia, that on the one hand it is the party which went to the greatest lengths in its attempt to combine the communist system with the principles of democracy that were deeply rooted in its society, while on the other hand it is the party which was perhaps most Stalinist in its actions both after 1948 and again after 1968?

Of course that’s something we could trace much farther back into history, the so-called bolshevisation of the KSC in 1929 was also the latest to occur, when the other communist parties already existed, but it is the most hard-line party. I would associate this with a certain effort or trend which exists in Bohemia and which not only is inherent to the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia but also has something to do with the so-called national character. People may become enthused by a certain idea, and in their enthusiasm, they are capable of showing great self-sacrifice and engagement. And if defeat follows, they immediately lose all hopes, defeatism prevails, which perhaps has its historical roots in that after the massive defeats of the Hussites and the loss of national sovereignty, which then lasted three hundred years, from 1620 to 1918, there is something in people’s consciousness that if the force really wins, it is necessary to capitulate. And this powerful tendency to capitulate that has always been in Bohemia has always surfaced in the KSC as well, when what were originally highly enthusiastic attempts to achieve something independent, original, democratic in essence, were defeated.

And how do you think that Gorbachev and his policy could influence the future development of the systems in Eastern Europe?

In Eastern Europe in general, not only in Czechoslovakia? You know, there is something absurd or paradoxical in that in almost all the smaller Soviet Bloc countries there were attempts to make economic and democratising reforms. They were in Poland, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, East Germany, but they always faced resistance from the Soviet Union. At that time the Soviet Union always violently intervened in the development of the individual countries. Now that the Soviet Union as the parent country of this system is finally coming to the conclusion that reforms are necessary, because the Soviet Union itself cannot go on like that any more, and that it is no longer possible to become a modern industrial country with this system, apathy prevails in those countries, they have their experience with defeats, the situation is actually different in every country. And the Soviet Union, for the first time, it seems, does not intend to directly interfere in these matters, for instance by replacing the party leaderships in line with the opinion of the momentary Soviet leader. I think it does so not only because of some ideals of not interfering, but also to avoid responsibility for what is going on there, and it often does not know what should be done in which country, and also because the experience from the Khrushchev times is that when a reform begins in any of these countries, it takes a different course than in the Soviet Union and it then reflects badly on the Soviet leadership, too, which I think eventually satisfies itself with the situation when nothing special is happening there, when things are rather quiet, but not that there should be trouble threatening to erupt, like in Poland or possibly in Romania. But the Soviet Union cannot do that now. Despite that, I think Gorbachev is a new chance for reforms in these countries as well, but it is merely, I’d say, a condition for that, and the key forces that will set the reform processes in motion in these countries must come from inside each country. And the shape of these reforms would differ in each country, it would be different in Poland than it would be in Czechoslovakia, and in Czechoslovakia different from Bulgaria, even if there were room for that without Soviet interference in all these countries. And what it’s going to look like, I don’t know. The future will show us.

Zdeněk Mlynář (1930–1997)

Politician, lawyer, political scientist and teacher

As a member of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia, he graduated from the Faculty of Law of Lomonosov University in Moscow and worked at the Institute of State and Law of the Czechoslovak Academy of Sciences. During the Prague Spring in 1968 he was involved in the preparation of the Action Programme of the Communist Party and was elected Secretary of the Party Central Committee. After the invasion of Czechoslovakia by the Warsaw Pact armies in August 1968, he and other members of the Czechoslovak leadership were abducted to Moscow, where under duress he signed the capitulating so-called Moscow Protocols, which rejected the ideas of the Prague Spring and accepted the occupation of Czechoslovakia as fraternal international aid. As a representative of the pro-reform process in Czechoslovakia, he was gradually stripped of all political offices and eventually expelled from the Communist Party. After the signature of Charter 77, he was forced to emigrate, settled in Austria and lectured in political science at University of Innsbruck. After the fall of the Iron Curtain, he returned to Czechoslovakia, but was unsuccessful in his attempt at a political comeback. His funeral in 1997 was also attended by Mikhail Gorbachev, formerly his classmate from the Lomonosov University. Mlynář was the author of many political science studies and essays. Perhaps his most well-known work is his memoirs, Mráz přichází z Kremlu [Frost Comes from the Kremlin] (1978).