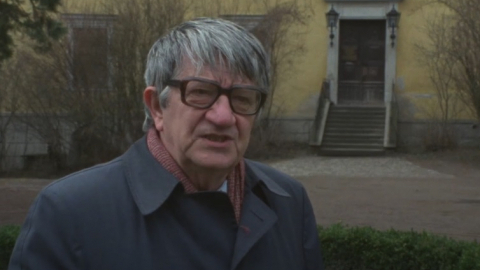

Jan Vladislav, 31. 1. 1988, Castle Schwarzenberg, Scheinfeld, Germany

Questions to the narrator

- 00:00Czech culture, Czech literature, and more generally perhaps Central European culture, has had close ties with the Western tradition. What happened to those close ties with Paris, with London, after 1948?

- 00:00So it can be said that the Central European cultural identity has persisted and survived this forty-year-long pressure?

- 00:14How would you define independent culture?

- 00:54For most people in the West the samizdat culture is a phenomenon of the last 15 or 20 years, but could you tell us through your own experience about its roots and about its origins?

- 02:53How would you explain why so many leading intellectuals were attracted by the communist ideology?

- 04:53The Prague Spring of 1968 is always presented as a great day for reform communists but how did people like you experience it?

- 06:11You have often described the experience of writing for the samizdat as a liberating experience for the writer. What do you mean by that?

Metadata

| Location | Castle Schwarzenberg, Scheinfeld, Germany |

| Date | 31. 1. 1988 |

| Length | 07:34 |

Watch and Listen

| Full video (mp4, 7 min) |

| Preview video (mp4, 1 min) |

| Audio track (mp3, 10 min)

|

TranscriptPlease note that this transcript is based on audio tracks and doesn't have to match exactly the video

How would you define independent culture?

No literature is independent, because it is dependent on its language, on its country, on the world in which man lives. But in countries such as Czechoslovakia this problem exists in a different form: writers want to be independent of external influences, they don’t want to be dependent on power, on orders from power that come from outside literature. And this is actually the significance of that whole Czech literature which is called independent, unofficial, and so on.

For most people in the West the samizdat culture is a phenomenon of the last 15 or 20 years, but could you tell us through your own experience about its roots and about its origins?

I believe that independent Czech literature does not begin in 1969–1970 as a heritage of the Prague Spring. It begins much earlier, in 1948, when the Czech intelligentsia divided itself into two groups, i.e., those who cooperated with the new communist regime, whether due to their beliefs or out of opportunism, and those who knew that by then the most important game was already being played, concerning Czech identity. That means the threat of losing Czech identity after 1948. And that’s when a group of writers, there were many of them, began to work independently of the conditions imposed by the regime, state publishers, and so on. And they were often also big authors who were allowed to publish, but at that time they had written some important works which were banned from being published. And there was another group, many younger writers, who were not allowed to publish at all and who then began to work outside the area of official media, publishers and the like.

How would you explain why so many leading intellectuals were attracted by the communist ideology?

On the one hand there were certain illusions, but on the other there was also a lack of courage to look into the face of reality. Some had already done that in the 1930s during the Moscow trials. And there were also other factors then, for instance, that most of intellectuals had, let’s say, a good family background and felt remorse towards the working people whom they did not know but on whose behalf they spoke. And that’s why they were willing to accept something that they thought was the working class dictate, which was not true, they did not understand that, but accepted it and submitted themselves to things they deeply disagreed with. This is also why so many older as well as younger authors in 1968 suddenly realised that this was not true and chose a different way. And truly independent literature therefore enriched itself with people who had supported the regime earlier. Suddenly they crossed over to the other side of the barricade and became organisers of the new wave of independent literature. One thing has to be said, which is very important, i.e., that only after 1968, thanks to these people who came from the structures, did independent literature come to be organised in an impressive way. For instance, the Petlice [Padlock] Edition became something that was really well organised, while before it had been handled in piecemeal fashion. And the result is that today you have not only a lot of editions but also a lot of journals, which is extremely important. There are review journals that officially have not existed in Bohemia since 1948, and only after, say, 1970 production started of independent historical and independent review journals, and the like.

The Prague Spring of 1968 is always presented as a great day for reform communists but how did people like you experience it?

The Prague Spring cannot be thought of as a kind of beginning and the result of mere communist traditions or pressure from the communist intelligentsia. It is the result of a great development which started in 1948, when the intellectuals who took part in the first wave of unofficial free thinking created pressure which led to a certain revision. And that was carried out especially by the intellectuals in the party as they had opportunities. The others only had moral opportunities to create pressure, while the intellectuals who were party members had the possibility to vote and do something. That’s why I also think that the development from 1948 to 1968 was very important, when a certain section of important writers and intellectuals was putting pressure, one way or the other, on the executive power of the Communist Party.

You have often described the experience of writing for the samizdat as a liberating experience for the writer. What do you mean by that?

What I mean is that writers as well as other people who were honest and wrote well still counted on the fact that their book would be published. They had to take into account censorship and self-censorship, and they imposed it on themselves. But when they saw after 1970 that their books would no longer be published, or at least not in the near future, they liberated themselves from censorship and primarily from self-censorship. This was a great stimulus for a certain kind of freedom. And this freedom manifested in that it unexpectedly emerged in a difficult situation, when they worked without author fees, without money, as operators in boiler rooms and the like, but they began to write very important books. It is significant that most of the works which are published today in the West, in France, England, and so on …

Czech culture, Czech literature, and more generally perhaps Central European culture, has had close ties with the Western tradition. What happened to those close ties with Paris, with London, after 1948?

I think that the regime primarily wanted to break any traditions and install its own. But it failed to do that. And it wanted to break the contacts with the world which were inherent in Czech culture, this means with the West: France, England and so on, of course Germany as well, and at the same time it also wanted to break the traditions with the East, with Soviet literature, but it meant the Soviet literature of the 1920s and 1930s, which was not allowed to be printed, published and received. I think this was primarily an issue of identity, as they wanted to remove the Czech, Central European and European identity from Bohemia and replace it with something to be called international identity, which was supposed to be something that could be replaced at any time, just like you can change street names, when for a while it is Foche Street, then it’s Stalin Street, each time it is different. And this international identity was supposed to be a sort of way of losing or removing the original Czech identity which was important for life as a whole. And I think that this began mainly in 1968, when the regime realised that before 1968 even the official literature was after all Czech in some respects. And then they wanted to install something that would be purely Soviet, but of course they presented it as international.

So it can be said that the Central European cultural identity has persisted and survived this forty-year-long pressure?

The 1950s were a tragic time. But on the other hand, they were a great victory for the Czech intelligentsia who, despite this cruel pressure, has persisted to this day. And that’s something which is often forgotten. They speak about the suppression, concentration camps, the prisons of the 1950s and the imprisonments of the 1970s. What is, however, not spoken about is that a major part of the Czech intelligentsia, and with them Czech readers and the Czech public in general, withstood that pressure and has not lost this intelligence of its own, its identity. And that is also important today – you see the “renewal” of religion, “renewal” in language, resistance to change of orthography and the like. All of this is a testament to the fact that they did not succeed in making deep changes to this original, traditional identity which dates back to the 10th – 12th century, since the christening of Bohemia, to today. I don’t think this would be a solely Catholic, Christian identity, it is the Czech identity.

Jan Vladislav (1923–2009)

Poet and translator from English, French, German, Romanian, Russian, Ukrainian and, with assistance, also from Japanese and Chinese.

He studied comparative literature at Charles University but was expelled from his course after the Communists seized power in 1948, and was unable to complete it until 1969. From 1951 he earned his living translating but was not allowed to publish his own texts. During the Prague Spring, he helped to establish the Circle of Independent Writers. After the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968 he was appointed chief editor of the World Literature revue, but soon was re-entered in the list of banned writers. He founded the samizdat edition entitled Kvart and, together with the Societas Incognitorum Eruditorum initiative, published Acta incognitorum, a cultural and political monthly. He was one of the first signatories of Charter 77. Forced to emigrate in 1981, he went to France to give lectures on unofficial culture in the Soviet Bloc, and collaborated with the Czech newsroom of Radio Free Europe and Deutschlandfunk. He assisted in the founding of the Czechoslovak Documentation Centre of Independent Literature, first in Hannover and then in Scheinfeld. After the fall of communism, he published his texts in Literární noviny and later moved to Prague.

He published hundreds of reviews, articles and essays in many periodicals, such as Svědectví, L’Autre Europe and Lettre Internationale (Paris), Listy (Rome), Acta (Scheinfeld), Index on Censorship (London), Obrys (Munich), Kritický sborník (Prague) and many others. He wrote several collections of poetry and essays, hundreds of book translations and numerous children’s books.

In 1991 he was awarded the Order of Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk by President Václav Havel. He held the French Order of Arts and Letters (1983) and several other prestigious awards.