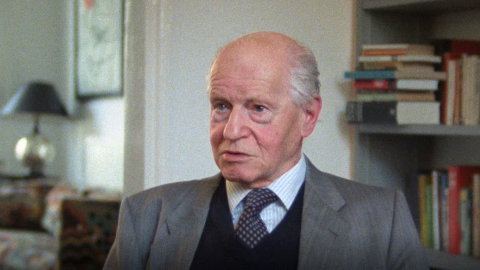

Vilém Bernard, 12. 11. 1987, Central Europe

Questions to the narrator

- 00:00Are you saying there was a group of Social Democrats that were sympathetic to the Communists?

- 00:57Did some Social Democrats have illusions about what the communists running the country would mean?

- 02:00So would Social Democrats split and did they have illusion?

- 02:51And did the Social Democrats have illusions about the communists?

Metadata

| Location | Central Europe |

| Date | 12. 11. 1987 |

| Length | 04:51 |

Watch and Listen

| Full video (mp4, 4 min) |

| Preview video (mp4, 1 min) |

| Audio track (mp3, 12 min)

|

TranscriptPlease note that this transcript is based on audio tracks and doesn't have to match exactly the video

When you were in Moscow, what were the communist leaders saying about what they would do, when they took power in Czechoslovakia?

As far as I remember, among the communist leaders in Czechoslovakia were the exiled ones at that time, and the most important of those of course was Klement Gottwald. He was also the one with the greatest authority, always present, and he laid down the party’s policy for the future. I mainly remember how often he kept referring to one and the same idea. He was comparing the experience of the Communist Party over the twenty years of the free Czechoslovak Republic and he used to say this, as far as I remember: “At that time we had a perfect socialist and communist programme, precise ideas of how to transform Czechoslovakia from the socialist point of view into a truly socialist country. But after our experience we came to the conclusion that the main important thing was not the perfect political socialist programme, but the main problem for the party and the main problem [that] faced Czechoslovakia by that time was the question of power. It is true that we had a perfect programme, which we were satisfied with and which was supported by very many people, but we did not realise in time that the power remained in the hands of the opponents of the Communist Party, in the hands of the bourgeoisie, as at that time represented mainly by the strongest non-socialist right wing party, the Agrarian Republican Party.”

How important was the seizing of power to the communist leaders?

The Communist Party, I mean its leaders, believed that in order to bring about a socialist transformation of the country, something they saw as essential from their point of view, from the point of view of the communist ideology and aims, they believed that for this purpose they had to have a political party which was solely devoted to the idea, which was not willing to accept any real sharing of power with other parties, in order to somehow discredit and soften their own policy, but they had to have a united disciplined party that followed only communist ideas and the communist programme. That is why first of all they were concerned with shaping the strong organisation in their party. They were bent on creating what they called democratic centralism, which means a strictly disciplined party in which the political bureau decides what to do or lays down the rules, which are binding for all members without much free discussion. Yes, they had certain debates on the ideology which was not always comprehensible, certainly not to non-communists. They liked the prestige of a party which was above day-to-day ordinary problems but which could envision the future, the beautiful ideas of socialism and when communism would prevail all over the world, mainly in the Communist Party. That is why in the first period of its existence the party was devoted to the creation of what I think the Communist Party people themselves called the Bolshevisation of the Communist Party. Which means shaping the communist party in terms of organisation and the unity of policy along the Soviet pattern.

After the war, why did the Social Democratic Party in Czechoslovakia not offer more resistance to the communists when it became clear they were seizing power?

I should say there were quite a few reasons. It is really impossible to qualify the various reasons as to which is more important and which is less important. They were all very important, each in itself, and especially all of them taken together. First of all, the party was split. The party was really split among those who wanted to preserve the democratic tradition of the party and follow its democratic policy, which is based on not just one but on many political parties in the usual terms. Of course there are struggles and disputes between parties but they were united in one thing, that the party was not there in order to destroy other parties. They were realising that they had campaigned in free elections as far as they existed in pre-war Czechoslovakia, but not to the extent that the result of the election should eliminate any other party forever. But this was one reason. Another reason was there was a great deal of uncertainty whether the party would be created after the war as an independent party in organisational and political terms, separate from the Communist Party.

Can I just make this clear. There was a fear, the Social Democratic Party believed that it may not be allowed to exist by the Soviets?

Exactly. Yes, they feared that this would be prevailing for the Communist Party and its official interpretation of the policy of National Front. Because it was agreed between the political parties, certainly under communist influence and pressure, immunity in the very beginning, that the political parties should somehow create a certain union among themselves, called the National Front, which would agree on basic ideas of the state as the Communist Party saw it, but which would still allow each of them to be organised independently.

Was there a group of Social Democrats then? Are you saying there was a group of Social Democrats that were sympathetic to the Communists? They would be even when the Communists were seizing the police, and so on?

They were. Yes, there was some discussion about it, I might even say the discussion was perhaps a little uncertain, a little bit new in the very beginning, because people were afraid, recalling certain situations which had occurred in other countries, even in the part of Czechoslovakia which was freed from foreign occupation, from German occupation first. They were under the influence of what had happened in the Carpathian Ukraine, in the easternmost part of Czechoslovakia, where the communist party simply took power by force.

Sorry, can I cut you there. I think that’s going into too much detail actually for us in fact.

I would say there was a process in progress in Czechoslovakia in the development of the opinion of the people toward the parties. And if one-third supported or were not opposed to the possibility of the communists’ attempt to dominate Czechoslovakia, there were certainly more of them later than in the very early days of Czechoslovakia. In the very beginning, Fierlinger had far greater prestige than he would have later.

Did some Social Democrats have illusions about what the communists running the country would mean?

Yes, they did, they would ask the question time and again, will the country remain free? Would the party simply pursue the policy dictated by the Communist Party or by Moscow? This is the question which was on everybody’s lips, this was the question that was asked openly again and again at the time. So if it wasn’t all clear in the very early days of the country, it was definitely much clearer at the time of the Brno Congress. That was a fair assumption that the development was only in progress and would develop itself a little further. Another influence of course –

So would Social Democrats split and did they have illusion?

When the Social Democratic Party revived its activities after the war, which itself was not certain before it happened, it was not united. It was certainly not united enough to be able to produce one coherent policy which would be required for a major kind of policy for a successful opposition to the communist plans for domination of the country. This was far from that degree of unity, certainly at the very beginning of the of the party’s activities after the war.

And did the Social Democrats have illusions about the communists?

At the time, let us not forget that historically speaking, the Social Democratic Party and the Communist Party were one party, which had already split back in the early 1920s. But what remained from the unity of the party was still a certain less precise idea about unity, except the belief that unity means strength, except the belief that there are perhaps to some extent differences in methods, that perhaps the Communist Party were rather rude and the Social Democratic party were a bit tolerant and ready to engage in discussion. Then the answer of the many people who had that kind of illusion at the time was, well all right, so why not, why not join forces with the communists, even if we differ in certain matters, for instance we are for more democratic tolerant methods, and they are for some strong arm methods, the communists are even for the forcible seizure of power. Why not make one party, why not support the Communist Party, which is at least more consistent in its endeavour to transform Czechoslovakia along socialist lines.

Vilém Bernard (1912–1992)

Politician, an MP for the Social Democratic Party and the Chairman of the Czechoslovak Social Democracy-in-Exile

He graduated from Charles University with a degree in Law and was involved in the students’ social democratic groups. After the Nazis began to occupy the country, he illegally crossed the border to Poland and when the war broke out he went to the Soviet Union where he joined the Czechoslovak Military Unit in the USSR. Later he worked for the consular section of the Czechoslovak Embassy in Moscow. After the war, he was the chairman of the Political Department of the Office of the Chairmanship of the Czechoslovak Government, Foreign Secretary and a member of the leadership of the Social Democrats, in 1945–1946 a member of the Interim National Assembly and in 1946 he was elected an MP of the Constituent National Assembly. As a defender of the independent policy of Social Democrats separately from the Communist Party, he waived his parliamentary mandate after the communist coup d’état in 1948, went to exile again and settled in Great Britain. There he was a co-founder of the Social Democracy-in-Exile, and went on to become the chairman of its Central Committee in 1973–1989. He was a lifelong critic of possible cooperation with the communists and for the partner Labour Party he conducted an analysis of the causes of the success of the communist coup d’état in Czechoslovakia. At the beginning of the 1950s he was the representative of the Czechoslovak Social Democracy-in-Exile in international organisations and he organised the congresses of the Socialist Union of Central-Eastern Europe, for which he was the General Secretary in 1948–1989. For almost twenty years he also worked for the BBC Monitoring in Reading, published articles in the British and exile press and cooperated with Radio Free Europe.

The story of his life and political career was published by his wife Růžena in her book of memoirs Pohled zpět. Život ve vírech 20. století [Looking Back. Life in the Tumult of the 20th Century] (2003), which was complemented with a re-edition of Bernard’s paper entitled Kde básníkům se poroučí [Where Poets Are Commanded] which analysed the situation of Czechoslovak writers and culture in 1948–1956. Bernard also contributed to the collections Osmdesát let československé sociální demokracie 1878–1958 [Eighty Years of Czechoslovak Social Democracy 1878–1958] (1958) and Sozialdemokratie und Systemwandel. Hundert Jahre tschechoslowakische Erfahrung (1978).