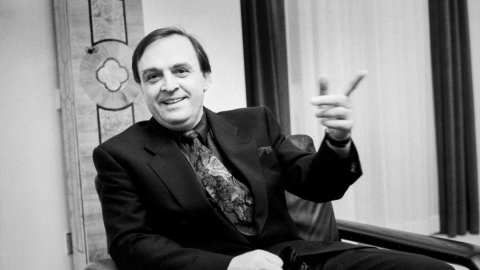

Jiří Gruša, 31. 1. 1988, Scheinfeld, Germany

Video for this interview was not preserved

Metadata

| Location | Scheinfeld, Germany |

| Date | 31. 1. 1988 |

Watch and Listen

| Audio track (mp3, 6 min)

|

TranscriptPlease note that this transcript is based on audio tracks and doesn't have to match exactly the video

How important to Czech culture and to the Czech people is the existence of the parallel culture, the intellectual and artistic underground?

Well, the existence of this culture is very important. It is something like a life vest in a plane, we are flying somewhere, we are hoping for a good landing but the future is something like a danger to all of us, and in this situation you have to have something like this equipment, and that is the existence of the parallel culture in Czechoslovakia.

Yes, and do the people of Czechoslovakia, I mean, lots of people there, do they regard the culture as important to them on an everyday basis? Do they read samizdat and so on, things like that?

They do. The prevailing opinion in Czechoslovakia, however, is not expressed by this culture. It is a small group, but an important one. The people are writing, they are reading, they are discussing, they are in opposition to the regime.

Why and when did you yourself decide to write for samizdat?

Oh, it was not my decision. I have tried to write my texts. That was not a political decision. I have written some texts, I have tried to publish them, but it was impossible. So I made some copies, I sent those copies to my friends, and suddenly the police came and arrested me. In my eyes this development was an apolitical one, but the texts I have written used different language. They used the language of normal Czechs, while the official language is, what’s the English word for it, Orwellian language. So it’s an ideological one, and if you try to express yourself in the real language, you can find yourself in trouble very soon.

Could you give one or two examples of censorship, the sort of things that are censored?

You are already censored if you publish – it’s not the real word for it: if you make some copies in the way I have done. But censorship in Czechoslovakia, or in the countries of Eastern Europe, is different because that is not censorship in the classical sense of the word. The old, or classical, censorship is trying to eliminate some thoughts, some ideas which were previously definable. But this censorship in Czechoslovakia tries to remove the people who under the circumstances would be able to express such thoughts, such attitudes.

Could you give some examples of things that are censored in Czechoslovakia today?

In practical term, censorship in Czechoslovakia affects any attempt to express anything in a language which differs from the permitted definition of reality or what the world looks like. It isn’t censorship in the classical style, where some unwanted thoughts are eliminated, following certain predetermined criteria. Here a certain kind of perception of the world is eliminated, along with certain potential bearers of this kind of perception.

Could say how important the emotional bonds are between people in groups like Charter 77, the bonds of trust and friendship?

This is also very complicated, as Charter, or opposition of this type, brings together people of most diverse opinions and backgrounds. Often they were enemies before, people who stood for various political positions. And it obviously happened that they became friends, but at the same time, as what they deal with and express is living material, they turned out to share an equally broad basis of different opinions and often avid discussions on a new platform. So in the future, should things perhaps develop in the same way as they have thus far, it may be expected that a relatively strong structure of pluralism, corresponding to the various political formations we know of in the West, could develop.

Jiří Gruša (1938–2011)

Writer and poet, translator, diplomat and politician

He studied Czech language, philosophy and history. In the 1960s he was one of the founders of Tvář [Face] magazine and contributed to the establishment of Sešity pro mladou generaci [Workbooks for the Young Generation]. Over the years he worked for several different publishers, most of which were prohibited in 1968–1969, and was prosecuted for his political views. After the Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia, he held a number of less qualified jobs and at the same time published his texts in samizdat and exile publishers. Ludvík Vaculík’s well-known samizdat edition Edice Petlice [Padlock Edition] was established with his contribution.

He was imprisoned after signing Charter 77 but was soon released following an international outcry. In 1980 he was awarded an American literary scholarship. The communist regime allowed him to travel abroad but revoked his Czechoslovak citizenship upon his return. Jiří Gruša then settled in Germany and worked on literature and translations.

He became a member of the editorial board and editorial council of Rozmluvy [Conversations], an exile magazine, and was a co-editor of Acta, an exile quarterly. After the downfall of the Iron Curtain, he had his Czechoslovak citizenship returned, moved to Prague and entered the diplomatic service, first as the ambassador to Germany (1990–1997) and then to Austria (1998–2004). He was the Minister of Education, Youth and Sports in 1997 and from 2004 the director of the Viennese Diplomatic Academy. In 2003–2009 he was the president of the International PEN Centre.

Besides his poetry, novels and translations, his bibliography includes dozens of studies, articles and reviews. He translated Franz Kafka, Friedrich Schiller and Reiner Maria Rilke from German. His poetry collections include Torna (1962), Právo útrpné (1964), Modlitba k Janince (1969–1973), Cvičení mučení (1969) and Grušas am Wacht aneb Putovní ghetto (2001) for which he was awarded the Czech ‘Magnesia Litera’ prize. Among his novels are Mimner aneb Hra o smrďocha (Atmar tin Kalpadotia) (1969, 1973 under the pseudonym Samuel Lewis), Dotazník aneb Modlitba za jedno město a přítele (1975 samizdat, 1984 Toronto), and after his return from exile they included, for instance, Česko – návod k použití (2001), Grušova hlídka na Rýnu / interviews with Karel Hvížďala (2011) and Beneš jako Rakušan (2011).

He was awarded the Jaroslav Seifert Prize, Magnesia Litera Prize, Andreas Gryphius Prize and Václav Benda Prize for his work.