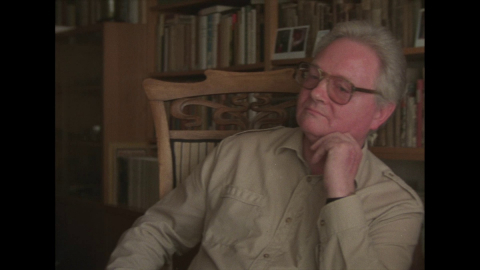

Claus Hammel, 28. 9. 1987, East Germany

Questions to the narrator

Metadata

| Location | East Germany |

| Date | 28. 9. 1987 |

| Length | 08:36 |

Watch and Listen

| Full video (mp4, 8 min) |

| Preview video (mp4, 1 min) |

| Audio track (mp3, 9 min)

|

TranscriptPlease note that this transcript is based on audio tracks and doesn't have to match exactly the video

The essence of the subject is: how do I learn the history of my people, of my country. What does it look like in the basement of my present (the present time). I start off with the working hypothesis: “One either has a complete history or one doesn't have any history at all.” This preoccupation with Prussia was not overdue, a preoccupation with Prussia has always existed. But within the Prussian history those tendencies were given a preference which highlighted above all the achievements of the Reformers after the victory over Napoleon; a dark and contradictory chapter was always the chapter of Frederic II; this chapter has been so complicated when, after the victory of the Allied Forces over Fascism, we destroyed the symbols which, within German history, were representative of Militarism.

Naturally, it is not a play about the Prussians but it is a play about our country and how it relates to its history. I am an opponent of any attempts to see history as a reservoir, the only use of which is that examples can be found there. Because Frederic II is no good as an example, he is still worth spending time on. However, and the play also expresses this, he is not going to be admired as a predecessor of our present history, as a binding predecessor, there are no comparisons today, there won’t be anywhere, history dates back over 200 years, but there is something which we must not conceal, for our own sakes. I return to the hypothesis: “0ne either has a complete history or one doesn't have any history at all.” The deciding factor is that we take a historic, that we take a historic figure with all its contradictions. That one cannot halve Frederic II into a good and a bad side and we forget about the bad side and emphasize the good sides. I think this would be a completely unacceptable procedure. In the play we talk about our contemporaries. How do we react to Luther, how do we react to Frederic II. Of what use is Frederic II: he is not of any particular use (sighing) except for the fact that he exists in our consciousness as an important predecessor who is very impressive to the world. Time will tell how to treat him, I think; after a long period of abstinence we have now reinstalled the famous memorial of Frederic II by Rauch in a riding position. It is not an object of worship. No flower arrangements are going to be laid down, no incense is going to be burnt, it is something which belongs to the town as it belongs to our history and it will be one memorial amongst many to remind us of him.

I think you have to ask the party but you can ask me since I am a member of the party. This play is part of the understanding we have of ourselves, of our life and our history. It is part of the qualities of the party as I understand it and as it is actually also laid down in the manifesto to always work at this self-understanding at new levels, to try to always acquire it afresh. This play is only a part of this self-understanding and I must say that I find it a very important part. The party doesn't start off with the day of its foundation, it doesn't start with its work in May 1945; it has its own history as it has had its own ups and downs and the time has now come, after having dealt with the important day-to-day issues, to look at our surroundings both in the literal and in the figurative sense. In this way there will be no attempt whatsoever to incorporate Frederic II into the party in retrospect, a danger which already existed in respect of Luther, the play hints at it, Luther as one of ours, a great revolutionary, he may well have been one, but only on a level which was possible to him. ”Revolutionary” is also a word which acquires a new meaning each day. Naturally, it has been one of my dearest wishes that this play should be performed in the centre of Berlin. At the feet of the memorial of Frederic II, in front of the Central Committee, in front of the State Council, that's where I believe that it belongs. And it was, though delayed, because it has only shown here for the past two years, in the country it has been playing since 1981, and it is urgently necessary to show the play there for an important reason, important for our life and not only for the life of the party, in order to gain self-awareness. I believe that this is an additional answer to your first question. The play serves the gain, the encouragement of historic self-awareness.

I don't think that this is a reconciliation with the Prussians, it is rather an acknowledgement of qualities which the Prussians had, of virtues as we say in our country and it is at the same time the acknowledgement of the enormous notion of militarism which is associated with the Prussians. Militarism is as much publicized, analysed and criticised as we are currently trying to work at finding a few positive aspects to it. I believe that this whole process is nothing else but an act of historic justice which we are trying to provide the Prussians with.

Claus Hammel (1932–1990)

Claus Hammel was born on December 4, 1932 in Parchim; he died on April 12, 1990 in Ahrenshoop. Hammel was a German playwright.

Claus Hammel was the son of a master saddler. The family lived in Parchim until 1934 and then moved to Demmin, where Claus Hammel spent most of his childhood and youth.

From 1949 he studied singing in West Berlin, but dropped out in 1950. In the same year he began to work in East Berlin for the FDJ in terms of cultural policy. In 1955 he became a theatre critic of "New Germany", and from 1972 Hammel was artistic director at the Rostock Volkstheater.

In 1958, Hammel made his debut as a playwright with “Here is a negro to lynch”, a new version of the play “Street Corner” by Hans Henny Jahnn. Many of his adaptations show clear differences to the originals in order to better correspond to the zeitgeist of the time and the ideology of the GDR.

In 1978, Hammel honored the founder of the Cheka, Feliks Dzierżyński, in the form of the original reading of his work "Reflections on Feliks D."