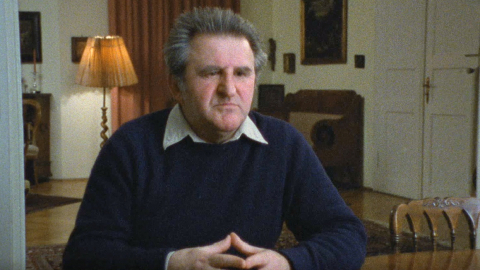

Karel Kaplan, 28. 1. 1988, Munich, Germany

Questions to the narrator

- 00:10But Gottwald perhaps did not believe they would win 50 percent.

- 00:52How were such allies found in the adjoining or competing political parties?

- 02:47How could one explain that not only the Communist Party but also other parties adopted a programme to nationalise the economy?

- 04:31This is actually the whole problem of the National Front, that it was democracy without opposition and it was not possible there to establish actual opposition against a specific decision of the government.

- 06:39So, the Communist Party could play on both sides, both in its parliamentary role in the government and institutions and at the same time also as a mass movement?

- 06:53What was the role of President Beneš in this period? A big discussion is now going on concerning his role as early as from December 1943, when he signed the treaty in Moscow, until February 1948. How would you analyse his role in this period?

- 09:24How can you explain that the February events went so smooth and the communist coup faced no great opponents from democratic parties?

- 10:59Could you describe how the Communist Party came to gain control of the security forces and the army?

- 13:49How did the communists liquidate their opponents after February 1948?

- 15:13To what degree was the whole strategy and the course of the February 1948 events coordinated with Moscow?

- 16:01And what about later, after February 1948, when the Communist Party had already seized power? In what way could the Soviet Union or Soviet authorities have interfered with Czechoslovakia’s policy or the security policy?

- 16:55In your book, you mentioned that in 1950 a conference was held in Moscow attended by the general secretaries and ministers of defence, where matters concerning the relationship between the Soviet Bloc and the West were discussed. What exactly was decided

- 18:05And developments in the individual socialist bloc countries should have followed this goal?

- 18:22How can you explain that political trials in Czechoslovakia had more victims than in any other socialist countries?

- 20:16Could you give us specific examples of how the security forces put pressure on the opponents of the Communist Party before February 1948?

- 22:43And could you also give some other examples of how opponents of the Communist Party were treated shortly after February 1948?

- 24:22The biggest trial of all was obviously the Milada Horáková trial.

- 25:29One question at the end: Could you compare and describe the difference between the repression in the 1970s during the so-called normalisation of society and the repressions in the 1950s during the period of Stalinism? What do you see as the main differenc

Metadata

| Location | Munich, Germany |

| Date | 28. 1. 1988 |

| Length | 27:26 |

Watch and Listen

| Full video (mp4, 27 min) |

| Preview video (mp4, 1 min) |

| Audio track (mp3, 30 min)

|

TranscriptPlease note that this transcript is based on audio tracks and doesn't have to match exactly the video

How can one explain the support which the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia gained after World War Two in the broad layers of society?

There isn’t just one reason, but I would mention three of them which, in my opinion, are the key ones. Firstly, it is the Munich Agreement and its consequences for the national awareness of the inhabitants. For them, the implication from that was that the Soviet Union would guarantee security for the future Czechoslovakia, and communists were the closest allies of the Soviet Union. Secondly, there was the fact that communists were perhaps the only party to have a programme and be able to lay out the requirements for what was important for the various groups of inhabitants. And thirdly, it was the fact that the communists presented themselves as excellent organisers from the beginning. In the wake of the Soviet Army followed brigades of Communist Party organisers who set up communist organisations and cells in towns and villages. And by doing so, they in fact laid down the foundations for the party structure, which was a very dense network.

So was that a specific feature of the Communist Party compared to other political parties?

The other political parties lacked this organisational support and did not have stable and precise programmes.

What then was the strategy of the Communist Party in 1945–1948?

The communists were returning to a liberated republic with an absolutely clear idea – gain a monopoly of power. Their original idea, however, was not like what emerged in February 1948. They had originally thought that they would form a kind of socialist bloc in which they would play the leading role, and the three socialist parties would gradually merge into one decisive party. There were also parties in the National Front other than the socialist bloc, namely the People’s Party and in Slovakia the Democratic Party, but they didn’t have a decisive majority in the whole republic. When this tactic failed in autumn and winter 1945 and the National Socialists, one of the socialist parties, turned right-wing, the communists thought they’d make up a left-wing bloc of themselves and the Social Democrats, and the bloc would have the majority, which actually happened in the May 1946 parliamentary elections. These elections, which saw a great victory for the communists with over 40% of votes nationwide, led them to the idea: “We will win the votes of the majority of the nation in the next election and will have the decisive position,” and, as Minister Kopecký said, “we will choose those who dance to our tune.” This was their basic trend. However, at the moment when they became isolated in the National Front, and especially after August 1947, after the Marshall Plan, they began to focus on gaining a monopoly of power by all parliamentary means, if possible, and extra-parliamentary means, if that was not possible. That was their intention from mid-1947.

But Gottwald perhaps did not believe they would win 50 percent.

Chairman Gottwald was one of those who thought that they would miss by a few percent, perhaps 4–5%. But his tactics were to resolve the matter of power by subverting non-communist parties, “cutting off” their leaders and installing collaborators who would be loyal to the communists. And by doing so, he would in fact make it one unified party. He was convinced that he’d gain enough MPs from non-communist parties who would ensure the majority he needed.

How were such allies found in the adjoining or competing political parties?

It wasn’t so difficult at the beginning. Initially it was only a group of people, most prominent in Social Democracy. Many former Social Democrats wanted to join the Communist Party, but the communists sent them back to their own party to work for the communists as and when necessary. A similar situation was seen with the National Socialists. There was a faction from the trade unions whose leader wanted to enter the Communist Party, but was also sent back. This was one group, forming a kind of core. Then there was a group of people that reeked of the Small Retributive Decree. They had some history of collaboration with the occupying power. It was not serious but there was a record in their file. And those were the people that the communists gained. They were not satisfied in their parties and began to cooperate with the communists. And eventually there was a group of those who were dissatisfied with their position in the party, for instance, Emanuel Šlechta in the National Socialist Party, whose candidacy was rejected and who later also collaborated with the communists. So there were a few such groups, but there was also a strong enough movement among the members of those parties, especially in Social Democracy, which preferred cooperation with the communists.

How could one explain that not only the Communist Party but also other parties adopted a programme to nationalise the economy?

As regards the programme of the nationalisation of industry, which was actually one of the greatest in Europe after World War Two, it was as follows: The communists originally conceived the first government programme not expecting nationalisation to come immediately, but at a later time. But Gottwald then spoke to President Beneš, who said that he would accept and sign proposals to nationalise. Beneš did that because he wanted to avoid a situation where nationalisation would later become the source of political crisis and political struggles. And Gottwald went back to the chairmanship meeting and said, “Beneš wants to sign the decree, so we have to take advantage of that and push through our party line, this means extensive nationalisation.” Originally they had thought that only military and large-scale industries would be nationalised, but then it expanded more and more. All the political parties agreed to nationalisation, but not all of them approved such a broad scope. The People’s Party and Democratic Party opposed this, but they knew their fight was actually meaningless because nationalisation was carried out by presidential decrees, and there was a majority of communists and social democrats in the government which decided that, who were in favour of nationalisation. There were objections from other political parties, minor adjustments were made to the decrees, but no big changes.

This is actually the whole problem of the National Front, that it was democracy without opposition and it was not possible there to establish actual opposition against a specific decision of the government.

Yes, the National Front was a special type of coalition based on people’s democracy. They made, as I put it, a certain cage for themselves, in which all of them were locked and none could fly out because as soon as they would do so they’d be done away with. As Gottwald used to say: “Well, if you leave the National Front, the Minister of the Interior has the right to dissolve you, as there is no dealing with anyone here outside the National Front.” In fact, the other parties did not want to become the opposition because they knew from the times of the First Czechoslovak Republic that opposition is easy to go to but difficult to return from. Only the Democratic Party expected to become the opposition. And when Gottwald could not reach an agreement on the ministerial posts with the National Socialists in 1945, he even considered putting them out of the government. The Social Democrats were against that, saying “If they leave the government they will win the vote from all those dissatisfied with the government and become the strongest party, or will be a very strong party, and that’s not good for us.” But it must be mentioned that even within this people’s democracy, an opposition turned out to exist. It was unofficial, but the non-communist parties submitted opposition drafts in Parliament, outside Parliament and in the press. And especially communists, when they could not promote something, had an excellent platform of opposition – the trade unions, which were actually an equal partner to the government and were fully under the influence of the communists and promoted their requirements.

So, the Communist Party could play on both sides, both in its parliamentary role in the government and institutions and at the same time also as a mass movement?

Yes. When they failed in something, they acted as a mass movement.

What was the role of President Beneš in this period? A big discussion is now going on concerning his role as early as from December 1943, when he signed the treaty in Moscow, until February 1948. How would you analyse his role in this period?

As regards 1945–1948, President Beneš laid out his primary position as being a non-party top official, the highest official of the state. And he more or less maintained this role. Whatever the government delivered to him to sign, what the National Assembly decided and what the National Front resolved, he signed. The mistake of the non-communist opposition was that they expected him to be the leader while he never made a decisive standpoint in favour of one side, his goal was always reconciliation. And when it was necessary for him to show his authority, which means in February 1948, he never did that. I think he made a great political mistake then. He declared February 1948 as a second Munich for him, and resolved it in the same way – appointed a government and resigned. But he should have done it the other way round – resign and not appoint a government. That would have saved his moral and political power. But frankly, his position was very weak in February. The conflict was actually developing along two lines – one was the resolution of the government crisis, which meant a new government, where the role of President Beneš was decisive as the one who would dismiss and appoint the government. But the second and main line was the struggle for power, which meant the rise and victory of the monopoly of communist power. And Beneš did not have much choice there. The non-communist political parties played the lead role. And they exhibited a serious lack of political skills then.

How can you explain that the February events went so smooth and the communist coup faced no great opponents from democratic parties?

It basically faced opponents, but not in public. No political party openly organised something that would work like an opposition against the communists, by saying this I mean a public movement. My explanation is that the non-communist parties decided to undertake a specific step without elaborating on its consequences. They thought that they were in a parliamentary democracy and that the government crisis would be resolved adequately, i.e., the president would approve their resignation, appoint a new government, and so on. But they forgot that that was not how the communists would resolve a government crisis. And the communists immediately organised an enormous movement and political parties in fact ceased to play an important role basically the next day. They were not prepared for that, to organise an effective counter-force.

Could you describe how the Communist Party came to gain control of the security forces and the army?

It wasn’t so difficult with the security forces because they had the Minister of the Interior, Václav Nosek, and a special institution called State Security, or the political police, began to be established there, along with a defence institution, the Security Department, which was to search for war criminals in Czechoslovakia who were to be prosecuted. And this other institution was slowly liquidated and merged fully with State Security as the domestic political intelligence service. So the communists controlled security, especially the parts which covered political and state security. It even went so far that there were no intelligence headquarters, and the function was in fact acquired by the registry department of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia, which the communists in these state security and police units reported to. It was more difficult with the army. General Svoboda, the head commander and the Minister of Defence, was on friendly terms with the leading communists and close to them, but most of the officers came from the resistance in the West and made up the major part of the personnel. Despite that, the communists successfully built up a structure of their secret organisation among the officers in two years, and their own data show that among the officers approximately 25% were communists. It was much higher among the ordinary soldiers, their data showed some 50%. So although it was forbidden to establish party organisations in the army and security forces, the communists had secret cells inside them, controlled by the district party organisations, and established a network in the army, which was very important.

How did the communists liquidate their opponents after February 1948?

It was a very simple method. Gottwald declared on the day after the beginning of the government crisis: “Establish action committees of the National Front and carry out purges everywhere.” So the action committees of the National Front were established in the factories, authorities and municipalities. The communists had the majority in them and carried out purges to remove those who did not show sympathy towards them or who stood against them politically. The power of these action committees was so strong that they even prohibited ministers who had resigned from entering the authorities, and the ministers in fact never went back to their offices. The opponents were eliminated within a short time. And Gottwald entertained the possibility of having an opposition party after February 1948, but then said, “No one wants to go to the opposition.” His idea was that it would be good to have an opposition party, so that at least they knew where the opposition was. But it was merely an idea.

To what degree was the whole strategy and the course of the February 1948 events coordinated with Moscow?

I don’t think there was much coordination. But some security officers had close links with their Soviet colleagues and reported to Moscow about the situation in Czechoslovakia, and among them was an absolute majority of those who said that the communists would not gain more than one-half of the votes and that some change should be brought. That influenced how the opinion in Moscow was formed concerning developments in Czechoslovakia.

And what about later, after February 1948, when the Communist Party had already seized power? In what way could the Soviet Union or Soviet authorities have interfered with Czechoslovakia’s policy or the security policy?

Very easily: through a network of advisors. It was established in the key power institutions, namely in the army, security forces, later also economic bodies, and it was used for that. Another such option was COMECON, and the third was the Information Bureau of the Communist Parties, which was not dissolved until 1956. Another important factor were the messages, opinions and moods of the leaders, especially Stalin’s, which were then transferred to Prague.

In your book, you mentioned that in 1950 a conference was held in Moscow attended by the general secretaries and ministers of defence, where matters concerning the relationship between the Soviet Bloc and the West were discussed. What exactly was decided at the conference and how were these dealings held?

The conference was held in January 1951 in the Kremlin. As you said, general secretaries and ministers of national defence of each country were there, and this was attended on behalf of the Soviet Union by several dozen generals and marshals and Stalin. It was basically to discuss military matters and the primary importance of this meeting was that Stalin declared a certain concept assuming that within 3–4 years socialism could be spread all over Europe by military means, but not later.

And developments in the individual socialist bloc countries should have followed this goal?

The entire military as well as economic policy followed this goal because basically it was a matter of three years.

How can you explain that political trials in Czechoslovakia had more victims than in any other socialist countries?

Only with political trials of leading communists, otherwise it is difficult to find, but for instance the Milada Horáková trial was the largest in the numbers of sentenced and death penalties. As regards trials of leading communists, who suffered the most as far as sentencing and death penalties, my explanation is that it was primarily a trial against people who were in some way linked to the West, the western resistance or western communist parties, and there were a lot of such people in Czechoslovakia, including those in high posts. Another such aspect was that the trials in Czechoslovakia were in fact delayed. It was the beginning of the second round of big trials, which eventually did not start. And because they were late there was a different ideological concept in them. The concept was anti-Zionistic and anti-Semitic, and there were many such people in various posts in Czechoslovakia, too. That’s why many of them also stood before court and were imprisoned. These are the two main reasons. Otherwise, it is hard to find specific causes.

Could you give us specific examples of how the security forces put pressure on the opponents of the Communist Party before February 1948?

I think that perhaps the most classical example of that were the “police cases” as I call them, when the communists in the security forces induced provocations against the leading officials of non-communist parties. One such provocation happened in Slovakia, where the communists in security forces used their own agent who brought illegal flyers from abroad and was to establish contacts and a connection with the leading officials of the Democratic Party of Slovakia. Based on the testimony of this agent, some forty leading officials of the Democratic Party of Slovakia, including two general secretaries of this party, were arrested later. If February 1948 had not happened, the whole fabricated story would have collapsed because these people would have testified before the court quite differently to how they were forced to testify by the security forces. But February “saved” the whole affair and all of them were sentenced after that. A similar action was conducted against the leading officials of the National Socialist Party, the so-called North Bohemian affair, when a military officer was arrested for allegedly having had a connection to the representatives of the National Socialist Party and prepared the so-called anti-communist coup. All of that was a provocation and only the February coup stopped it.

And could you also give some other examples of how opponents of the Communist Party were treated shortly after February 1948?

Immediately after February 1948, most of the officials of non-communist parties which the Action Committees of the National Front had deprived of their political offices, were affected in social and existential terms unless they were workers. They were fired from the authorities and had to leave their posts. Many of them, including MPs, were imprisoned, put before the court and sentenced in the following years. But immediately after February 1948 some two or three MPs were arrested. One of them, the People’s Party MP Sochorec, either committed suicide or was killed, I don’t remember exactly, but he died in prison. But at the beginning the campaign against MPs wasn’t successful. Gottwald wanted to keep up appearances and respect the parliamentary immunity. Anyway, shortly after the new elections in May 1948, the campaign against leading officials of non-communist parties was launched, and a greater part of them ended up in prisons.

The biggest trial of all was obviously the Milada Horáková trial.

Yes, the trial of Milada Horáková, a National Socialist Party MP, was the biggest. Other National Socialist Party MPs and other officials of the People’s Party and Social Democratic Party were also involved. After this trial, which resulted in I think eight death penalties including Milada Horáková, who then had a 16-year old daughter and who President Gottwald refused to grant a pardon, there were so-called subsequent trials, a kind of branch trials in each region. A whole network of trials was set up and fabricated in which some 320 people were sentenced, including over 20 death penalties.

One question at the end: Could you compare and describe the difference between the repression in the 1970s during the so-called normalisation of society and the repressions in the 1950s during the period of Stalinism? What do you see as the main differences?

I think there is a big difference. In the 1970s there was existential punishment and existential political and social persecution of tens of thousands of citizens, but in the mid-1950s there were tens of thousands of citizens who were unjustly sentenced to imprisonment, forced labour camps or other similar facilities. So the difference was big. Regarding social persecution, according to my calculations, approximately a quarter of a million people were unjustly punished by courts, by judicial and extra-judicial persecution in the 1950s, while in the 1970s the figure wasn’t that high. And as regards those affected in existential terms, there were at least four times as many.

Karel Kaplan (1928)

Historian specialising in the post-war history of Czechoslovakia

After the war, he entered the Communist Party, completed distance courses at the Institute of Social Sciences of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia (ÚV KSČ) and in 1960 began to work there in the field of ideological supervision over the Institute of History of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia. This gave him the opportunity to view as yet inaccessible archival materials including top secret documents of the Communist Party and its security services. As an ever louder critic of the post-war development of Czechoslovakia, he had to leave his job in the ÚV KSČ apparatus and began to work as an independent scholar at the Institute of History of the Czechoslovak Academy of Sciences. He supported the pro-reform processes of the Prague Spring in 1968 and worked as the secretary of the Central Rehabilitation Committee at the ÚV KSČ. After the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia in August 1968, he lost his job, was expelled from the Party and in 1972 was arrested and held in custody. Four years later he legally travelled to the Federal Republic of Germany where he managed to smuggle copies of many classified archival documents. He was subsequently deprived of Czechoslovak citizenship and prohibited from returning. In exile, he worked in contemporary history and published books. He collaborated with the Collegium Carolina in Munich and with the Voice of America, Radio Free Europe, the BBC and Deutsche Welle. After the fall of the Iron Curtain he came back to Czechoslovakia and worked at the Institute of Contemporary History of the Czech Academy of Sciences.

Karel Kaplan is one of the most frequently translated Czech historians and an important personality in the post-war history of Czechoslovakia, the author of hundreds of historical texts and dozens of books addressing modern history after 1945.

He was awarded the Medal of Merit (2008) by President Václav Klaus.