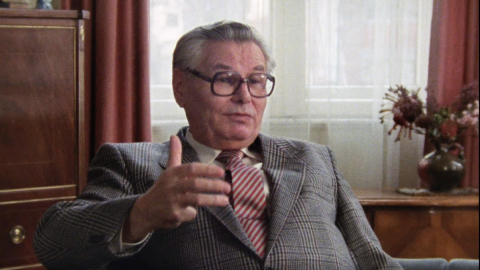

Ota Šik, 1. 1. 1988, Munich, West Germany

Questions to the narrator

- 00:12What were the causes of the crisis in the planned economy in Eastern Europe and especially in Czechoslovakia?

- 04:40But the economic crisis came in 1962 and the reform could not be put off after that. What were the main features of the reform that you proposed?

- 10:02A characteristic of the situation in the 1960s was that there was a kind of collusion between the supporters of economic reform and the supporters of political change, which then culminated in 1968. How did such a collusion come about? Can you remember th

- 11:10So the Prague Spring was a certain response, a key to the actual implementation of economic reform?

- 12:54So you participated in Novotný’s fall?

- 13:18At the time you also took advantage of public opinion and exploited television quite a lot. Can you reflect on your personal role and especially on the impact of your television appearances?

- 15:32As regards the Czechoslovak situation, there was an attempt to link the economic reform with the political reform in 1968, which was brought to an end by violent means. After that came the Hungarian experiment which, on the contrary, tried to introduce on

- 18:28So the threat of technological backwardness will push that system toward reform?

- 18:57You have mentioned the socialist market. It was your grand idea of the 1960s, to merge the plan and the market, socialism and a market economy. Could you tell us what this idea consisted of?

- 20:34And what is socialist about it? What does socialism consist of?

- 21:33Why is the apparatus so afraid of the market? Is it an ideological taboo, is it the loss of power? What is the reason for them being afraid?

- 23:18Reforms with Gorbachev are presently underway in the Soviet Union, everyone speaks about the reform and perestroika, but at the same time Gorbachev says that integration within COMECON should intensify, while for Eastern European countries reform always m

- 25:22I would like to return again to the situation in Czechoslovakia. There was a crisis to which a response came – your reform from the 1960s. This was “brought to a halt” by the Soviet invasion, the reform was over, but this economy has been functioning for

- 30:33I would like to return to the question of power. Why is the apparatus, the political power, unable to come to terms with the idea of real decentralisation, the autonomy of enterprises and market mechanisms? What is the main reason?

Metadata

| Location | Munich, West Germany |

| Date | 1. 1. 1988 |

| Length | 33:22 |

Watch and Listen

| Full video (mp4, 33 min) |

| Preview video (mp4, 1 min) |

| Audio track (mp3, 32 min)

|

TranscriptPlease note that this transcript is based on audio tracks and doesn't have to match exactly the video

What were the causes of the crisis in the planned economy in Eastern Europe and especially in Czechoslovakia?

The causes of the crisis were firmly rooted in the system, which is very primitive and not capable of compensating for the functioning of the market mechanism, and this became apparent quite early, in the very first years, so the first such crisis grew in 1956–1957. It was so serious that the rationing system was reintroduced, there were enormous problems in distributing supplies, the efficiency of production slumped so much that not even the state budget was certain, and there were enormous gaps in foreign trade. And then it was decided to introduce in Czechoslovakia the first so-called reorganisation of planning and management, which was prepared in 1957. A larger commission was established which consisted of representatives from various ministries, basically a bureaucratic commission, headed by the then vice-chairman of the Ministry of Planning, Rozsypal. And I participated in the work of the commission as the only theoretician, or quasi, so that they would have at least some sort of theoretician. I mention this because it was actually a schooling for us since in this reorganisation we did not succeed in achieving any of the proposed objectives. Nobody dared to substantially change the planning of directives. Only the number of indicators was to be reduced, enterprises were to be given a little more independence, and create some sort of interest in better productivity. But as the directive targets of the plan were not removed it soon crashed. In 1960 the new Five-Year Plan began, that is the third 5-yr plan conceived according to the Soviet model, where Khrushchev laid down big targets of growth to reach and thus surpass America in production per inhabitant, and that gave rise to a certain enthusiasm in Novotný’s leadership. The aims of the Five-Year Plan were quite inflated and soon simply prevented enterprises from showing interest and from becoming more independent, and led to nothing more than a purely formal drive for the fulfilment of the plan. But these targets were completely exaggerated and nobody dared to introduce new and better products and new equipment that would help to boost efficiency, so as a result the economy was plunged into a new and even deeper crisis in 1962. It was so bad that at the beginning of the 1960s Novotný criticised this reorganisation as being the cause of the lack of improvement in the economy and instructed a new centralisation. So at first we decentralised, and then we centralised again. In practice, this always means only a reshuffle. Something is merged and something separated, a new minister comes along, something is gotten rid of and something is reorganised, all forms and methods are changed.

But the economic crisis came in 1962 and the reform could not be put off after that. What were the main features of the reform that you proposed?

Yes, it was even deeper than in 1957. The national income had dropped in absolute terms, real wages of workers fell and the workers began to voice their dissatisfaction. Novotný suffered political problems at that time, he was facing controversies with Kolder and felt his position was no longer so strong politically. All the criticism was directed against him, and at that time, Novotný was constrained in looking for a way out. At the Institute of Economy –

Novotný felt he was in a weak position politically and criticism was directed against his leadership, and Kolder as an ambitious younger Secretary was pressing for Novotný’s position. At that time, Novotný was constrained in looking for a way out of the terrible economic situation, and at the Institute of Economy, where I was the director, we had already prepared a new model of a socialist economy in which we tried to rectify all the shortcomings and inconsistencies, having gained experience from 1967–1968. I managed to gain access to Novotný and tell him that we had to change something, that it was all bad. He immediately went for it: “Well, what do you recommend?” I told him we already had something, and that I had written an article which showed some solution. “And what about the article?” I said that Kolder has forbidden it to be published. That was like a red rag to a bull for Novotný. He immediately got on the phone and called Švestka to say that the article had to be published. And in this big article, published on more than two pages in the Rudé právo daily as an official opinion, I said things which were very critical and brand new, and showed in it that the mess was not the fault of the factories but of the planning system, and that the plan was unrealistic. And I went on to say that the whole planning system would bring no improvements. I suggested some paths to follow, and that aroused quite a strong response, delegations started coming, thousands of letters “from below”, people had been waiting for someone “from above” to tell them something like that. Novotný picked up the opportunity and I advised him that a commission for reform should be set up. He immediately accepted that and made me the chairman of the commission. So by the end of 1963 the reform commission began its work, and drew up a draft in a very short time, as the basic theoretical work had already been prepared. In the middle of 1964 it went through all the approvals, as is customary here. There was initially a bit of a struggle with the politburo concerning various formulations, but eventually they did approve. It went on to the Central Committee, then parliament, the government, and in 1965 it was scheduled to come into effect. And then something unexpected happened: Khrushchev was “removed” from power at the end of 1964. This was obviously quite negative for our plan, as Novotný felt he was on good terms with Khrushchev, who supported these experiments and approved this reform for Novotný. And when Khrushchev was “removed”, Novotný became nervous and afraid. He felt straight away that Brezhnev was not a friend of reform and that in the Soviet Union things were beginning to take a step backwards. They were changing everything that Khrushchev had initiated there, but that was no great loss as Khrushchev had in fact done a lot of nonsensical things.

A characteristic of the situation in the 1960s was that there was a kind of collusion between the supporters of economic reform and the supporters of political change, which then culminated in 1968. How did such a collusion come about? Can you remember that?

It did not happen straight away. At first there were mostly small spontaneous groups. There was unease and criticism from writers, in some universities, institutes and publishing houses. Then a legal commission was established led by Mlynář, where they began to consider changes to the political system. But you can hardly say that it was somehow directly divided, as we also had to always think in our commission about political changes, because economic changes without the corresponding political changes are untenable, at least in the long term.

So the Prague Spring was a certain response, a key to the actual implementation of economic reform?

Yes, and it has an important pre-history. The fact that Brezhnev had come to power made Novotný try to move away from the reforms. So while he supported them at first, he suddenly tried to prevent them. And he could not reverse them officially since all the state offices had approved them. He even had put out a lot of propaganda about them and promised that everything would be better, so now he tried to silently get rid of them, let it all dwindle away so that no one would talk much about them any longer. We saw that it was bad, that nothing would probably remain from all that work and everything that we’d expected. Novotný even did another terrible thing, that he officially assigned the implementation of the reform to the Ministry of Planning, which was ironic: we wanted to remove the directive planning, and Novotný assigned the reform to the hands of the ministry whose interest was to preserve the old system of planning. We saw that this would go nowhere, and so we began a political struggle against Novotný. In our commission, we, the core of the best people, told ourselves: “Nothing else can be done but Novotný must go if we are to preserve at least something.”

So you participated in Novotný’s fall?

Definitely. The speech I delivered at the Party Congress of 1966 was directly intended to criticise the lack of democracy also in the political sphere in the Party, and if the economic reforms were to be carried out, changes in the political sphere would also have to come.

At the time you also took advantage of public opinion and exploited television quite a lot. Can you reflect on your personal role and especially on the impact of your television appearances?

I think it was very important, because people would have been quite disorientated without it – at one moment we were for the reform, and in the next the reforms weren’t being spoken about. So those were the months when I wrote one article after another, so that an explanatory article would appear every week, I spoke on radio and on television, where there were six parts. People sat in front of their TVs and the streets were deserted. I tried to show them the truth, what the real situation was, and where we could have been if the system was different, and where we were as a consequence of the old system. And all this created such a strong public pressure, we had support “from below” which was so strong that Novotný did not dare to silence me after that in any way. He, for instance, tried to stop me from speaking at the 1966 congress. I was the first down for discussion and did not get my turn. He firmly ordered that I could not speak as he was afraid of my contribution. But the delegates kept coming every day to the chair’s table and asked “Why isn’t Sik speaking? We want to hear something about the reform”, and under this pressure he gave way on the very last day. My address was highly critical and even touched upon democratisation, and received such strong support and evoked such a response that they were unable to prevent it from being published, and that meant quite a lot.

As regards the Czechoslovak situation, there was an attempt to link the economic reform with the political reform in 1968, which was brought to an end by violent means. After that came the Hungarian experiment which, on the contrary, tried to introduce only economic reforms without political reforms. It was perhaps the antithesis to the Czechoslovak situation. How do you regard now with the benefit of hindsight the experience with these two cases and especially the problem of linking economic and political reform?

I consider the separation of these two spheres only possible for the short-term. I do not think it is possible to have a market economy in the long term – and I don’t mean Western capitalist market economy or the so-called socialist market economy – without a certain democratisation in the political sphere. But that does not mean that for a certain shorter time such a reform could not continue within the old political system, especially when there are people in the party and its leadership who are inclined toward economic reform, like for instance in Hungary. But even in Hungary it began to appear that it had its limits, because if we are to carry through an economic reform consistently, we cannot do so without a series of highly unpopular measures, I mean for the population. This means that if the socialist enterprises are to export to the West, and they must because without imports from the West, it would be impossible to catch up with the western technology and semi-finished goods which the eastern economy needs, and if these products from these socialist countries aren’t competitive on the western markets, import cannot be done to the required level. To avoid becoming indebted, Czechoslovakia limited imports for years. It is now becoming clear that it is terrible for the economy. Czechoslovakia completely neglected the latest technological developments which have been established in the West in recent decades, and it has been left completely behind in many electronic industries.

So the threat of technological backwardness will push that system toward reform?

Of course it is, because production isn’t as efficient and structurally as flexible as today’s western markets demand, and the economy is then unable to increase exports, and the only solution it can use is to constantly reduce imports.

You have mentioned the socialist market. It was your grand idea of the 1960s, to merge the plan and the market, socialism and a market economy. Could you tell us what this idea consisted of?

Of the correct implementation of market competition, market prices and also market pressure on the enterprises. Enterprises should not only earn when they manufacture well and flexibly for the market and satisfy demand, if they are innovative and bring new higher-quality products with which they win over the market, but they should also feel a certain amount of pressure. Enterprises which are old-fashioned, remain conservative and don’t produce new and better products and aren’t flexible, must lose out. And the loss must be so great that in some cases the enterprise will be forced to close down, although it may be helped just as it is in the West. A new objective and deadline is set, which the enterprise has to fulfil, and it must balance its accounts by a certain time. And if it fails there is no other choice but to close down such an enterprise. This means that enterprises must gain experience, i.e., with good work we will be profitable, we will cover wages and bonuses will grow, and bad enterprises will lose, their staff will lose, until eventually the enterprise will be liquidated.

And what is socialist about it? What does socialism consist of?

Socialism does not disappear when consistent market mechanisms are used. Socialism consists of two fundamental principles. One is that workers are the actual owners of the enterprise. Especially in large enterprises, something like real collective ownership must exist, collective responsibility and the possibility to elect the management. A collective which is facing losses and sees that the enterprise is being badly managed must also have an opportunity to dismiss the director and appoint a better director. This means that if we want someone to have a share in the responsibility and material right of recovery, complete democracy must be granted.

Why is the apparatus so afraid of the market? Is it an ideological taboo, is it the loss of power? What is the reason for them being afraid?

That’s obviously the other side of that coin. If we want such independence for market enterprises, we cannot regulate them from central headquarters by some directive indicators. The old directive-based plan must disappear. In its stead, something like a macro-plan, or general plan, comes, simply overall indicators of the national economy, which marks out the long-term aim of the economy’s development. These aims have to be realised by means of economic and political instruments, taxation and loan policy, state expenditure policy, fiscal policy and so on. These are instruments which can be united with the market mechanism without restricting it, but they are also instruments which the state can use to promote its objectives in the interest of the workers. And it would be even more socialist, because it would be more democratic, if such plans existed in two or three variants and the population could participate in their preparation, and then select one specific plan for their development. That’s where I see the substance of socialism. Socialism means deep and authentic democratisation. It means that the workers in enterprises and in the whole national economy and society can participate in decision making.

Reforms with Gorbachev are presently underway in the Soviet Union, everyone speaks about the reform and perestroika, but at the same time Gorbachev says that integration within COMECON should intensify, while for Eastern European countries reform always meant opening up to the West. Isn’t this a discrepancy between the reformist programme on the one hand and the increasing integration within COMECON on the other?

I don’t think there is necessarily a discrepancy. Long-term plans must make it clear in which branches and which sectors cooperation will be closer, but that must already begin in research, development, the introduction of new products, and that’s where a certain distribution of work between socialist countries can be of profit. But in the system which we mentioned, nothing may be set in a directive manner, forced on the enterprise, participation of the enterprise must be voluntary from the beginning, it must bring advantages, and some pricing mechanisms must also be in place, and enterprises should be involved by means of prices, too. If they were coerced to do something like the Eastern-style cooperation, which would result in losses or disadvantages, and if they were to hit on the fact that exporting certain goods to the West would lead to greater profits, there must be a pricing compensation in this. They must make decisions with their own interest at heart because that’s the only thing that serves the interests of the rest of society. If anything is brought against those interests, it is old-fashioned and contrary to the interests of the enterprise.

I would like to return again to the situation in Czechoslovakia. There was a crisis to which a response came – your reform from the 1960s. This was “brought to a halt” by the Soviet invasion, the reform was over, but this economy has been functioning for twenty years without reform. How is that possible?

There is functioning and then functioning. There can be a big difference. In those twenty years, Czechoslovakia –

It is important to realise that Czechoslovakia and, for instance, also East Germany, were industrially advanced countries in the past. There was an enormous difference between, say, Czechoslovakia and Poland, Hungary or Rumania. These two countries maintained this lead, which is why they are still leading the Eastern Bloc today. But that’s not crucial. These are remnants of the earlier capitalist development. As a matter of fact, even though they are ahead in the East, they are terribly behind comparable Western countries. Let’s mention a single fact, that before the war, the Czechoslovak economy was on approximately the same level as the German economy, which means that production per capita and standards of living in these two countries were roughly the same, even though Czechoslovakia was smaller in terms of population. And after twenty years, or in fact almost forty years now, of socialist development there is such immense underdevelopment compared to Germany that it is profoundly shocking. Product per capita in Germany is almost three times higher than in Czechoslovakia today. This means that real wages are almost 190% higher, almost three times the average wage in Czechoslovakia. And the same holds true in all other spheres, such as social welfare, healthcare, pension insurance, cultural development. In all segments, the German standards are many times higher than in Czechoslovakia. This is a dreadful indictment of the socialist economy, isn’t it? There were always claims that thanks to the socialist system the production strength would accelerate faster and we would move ahead of capitalism. In reality the gap between the East and West isn’t diminishing but increasing every year. So this is the answer to the belief that we had great successes and what our people achieved. Of course people were diligent and worked hard, but did only what the system allowed. And as regards some entrepreneurial initiative, i.e., innovations, technological progress, the system never allowed that. The only thing they achieved was in fact a political trick – after the occupation in 1968 and then the dismantling of the system we made, when it was all returned to the old system from the days of Novotný, they had to give something to the population. People were terribly upset by the military intervention and the removal of the reformists. That’s why they did the trick that through planning they increased production and imports of consumer goods at the expense of investments. Actually only a directive-based planning economy is capable of performing such large-scale and relatively rapid changes in proportions. But it is disastrous for the future. Living standards went up for a while, people were given something to keep them content, but in reality there was an immense slowdown in investment development. The whole modernisation has fallen terribly behind development in the West. And if you have an economy where you do not invest over a period of years, the effect is that in a few years it is unable to reach growth in production and especially in productivity as in those countries that created completely new foundations of production and technology in their enterprises with the help of investments.

I would like to return to the question of power. Why is the apparatus, the political power, unable to come to terms with the idea of real decentralisation, the autonomy of enterprises and market mechanisms? What is the main reason?

Because decentralisation itself, making the economic sphere independent, means that the party bureaucracy loses power over the whole of this massive area. Power itself simply corrupts a lot when a party secretary can decide who is going to be the director, who is going to be in the management, and what the enterprises should do, and when it can sometimes go much farther, when with the help of these enterprises he can receive certain services, when the enterprises which they can influence do illegal work for the secretaries, and the managers do whatever the secretaries order because of fear. When such independence is given now, the whole party apparatus loses its position of power. And another thing will be apparent here, that a major part of this bureaucratic apparatus becomes superfluous as it was inflated in size by the old centralised planning system. And when instead of this incapable planning the market mechanism begin to kick in and production becomes correctly directed, which means that investments follow needs, a major part of this bureaucratic apparatus will have no work left to do. And that means that those people who have become accustomed to ruling and to the various privileges which were part of it, are afraid of such changes. They know that unfortunately not all of them will be able to adapt to the new system. Many average and sub-average people who found a job as bureaucrats in the party apparatus will have a hard time finding an adequate position because they lack the sufficient qualifications. These people are afraid of new developments because they are concerned about losing their position and benefits.

Ota Šik (1919–2004)

Economist, politician, commentator and pedagogue

At first he began to study painting, which remained his lifelong hobby. During World War Two he joined the illegal Communist Party and in 1941–1945 was imprisoned in the Mauthausen concentration camp. After the communists seized power in 1948, he promoted the Soviet model of central planning of the economy, but the slowing down of Czechoslovakia’s economy forced him to change his mind at the turn of the 1950s and 1960s. In 1961 he was appointed director of the Institute of Economy of the Czechoslovak Academy of Sciences. One year later he was elected a member of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia and later the head of the State and Party Commission for Economic Reforms. He became well-known especially during the Prague Spring in 1968 as the author of economic reforms which were to revive the inefficient economy. He was appointed Deputy Prime Minister, travelled around the whole country, wrote articles, explained facts, spoke on radio and on TV, and promoted the so-called Third Way, i.e., a combination of a centrally planned economy with market mechanisms. He had his own keenly followed TV programmes in which he popularised reforms. By comparing the number of hours a worker in socialist Czechoslovakia and in capitalist Germany had to work to buy the same goods, he demonstrated that a centrally planned economy was untenable.

After the invasion of Czechoslovakia by the Warsaw Pact armies in August 1968, he went into exile in Switzerland. He taught in Basel, Sankt Gallen and Manchester (UK). The relatively good economic situation in Czechoslovakia in the 1970s and 1980s was also attributed to the fact that some of Šik’s reform proposals were actually carried out even though the communist regime never admitted that. However, for the new Czechoslovak leadership at that time, he always remained the symbol of the return to capitalism, and as a persona non grata he was even deprived of his Czechoslovak citizenship. He was the author of many specialised and popularising papers and university textbooks. After the changes in 1989, he was invited to join discussions about economic reforms, but his opinions were no longer relevant for the new circumstances, and this time the reforms followed quite uncompromisingly the road to a market economy.