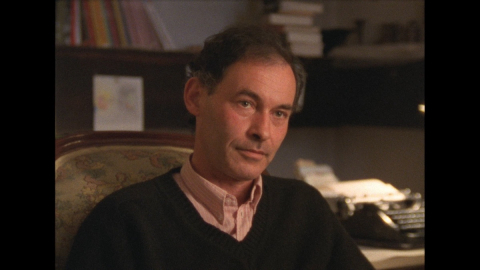

Mr. Król, 7. 6. 1987, ?

Questions to the narrator

- 00:08Is privatisation one of the possible forms of this emancipation of civil society from the grip of the party?

- 02:21But they would still be selling state books.

- 03:21How far do you think that this pressure, this principle of privatization can roll back?

- 04:09Why is this retreat of the party in Poland possible? Is Poland an exception or is this the future of the whole Soviet bloc?

Metadata

| Location | ? |

| Date | 7. 6. 1987 |

| Length | 08:07 |

Watch and Listen

| Full video (mp4, 8 min) |

| Preview video (mp4, 0 min) |

| Audio track (mp3, 8 min)

|

TranscriptPlease note that this transcript is based on audio tracks and doesn't have to match exactly the video

Is privatisation one of the possible forms of this emancipation of civil society from the grip of the party?

Yes, it means that if you get your own company and you get a lot of money, then you in a sense become independent. Of course not totally. And that is an interesting problem because you don't... You are still dependent in growing on the state or on the police or even secret police, so you must behave in a sense. And that is a problem how far you can go owning your own private company politically, how can you, how far you can get engaged and so on? Not to make them make a move against you, by police or by financial services. So on, fiscal services, but still, if you have a lot of money, then you become independent. When some group of people creates a company or something, they become independent. And it the present situation in the present state of Polish economy state must be very cautious. And if it wants to stop such an independence because it desperately needs anybody who can do something, produce something, produce anything practically. So I think it is important, although in a communist state, it never can be the main way. You cannot privatize as big things like Nova Huta or Huta Katowice or things like that. It is just unimaginable. And then nobody would buy them because they are just simply bringing enormous deficits. So that must be crazy. But still, this way, it's one of the most important now, not only in economy. I would say a kind of... we want at least to launch a campaign of making your own life, taking your own life in your own hands, which means privatisation of the state owned all bookseller shops are state owned in Poland. Why not change that into the privately owned bookseller shops? They would be much better, much cheaper and so on and so to.

But they would still be selling state books.

State books, but then you can make a choice. You can buy books published by this editor and not buy books published by another editor, buy these books and not buy that books. And that would mean that some books circulate because they are good, others don't, and so on. It would also be a privatisation this thing about theatre and whole culture, but it not. It doesn't concern only culture. It also concerns schools. I'm very much for small private schools for beginning children. My daughter actually is going to the school this year, and there is a possibility that she'll have to go either at 7:00 in the morning at 12 or five in the afternoon because the school is so full up. So I've proposed to parents around here that we create a private school for 10 children. We pay a amount which is not very big, but I don't want her to go at seven o'clock in the morning. That would be also privatization in this sense.

How far do you think that this pressure, this principle of privatization can roll back?

I think quite far. If they accept church also, because church wants to do a lot in the job of all social security, houses for grown, for old people and so on, which are in the awful state now in Poland. And if they accept associations because you cannot do all of those things alone, if you create association for better education of small children, for example, then we can do it together. Me alone, I cannot do that. So if they accept that, are they ready to accept that? I would say - half. They already because of the real pressures and they are also afraid of that?

Why is this retreat of the party in Poland possible? Is Poland an exception or is this the future of the whole Soviet bloc?

You know, I don't know about the future, but I would say Poland is kind of an exception because of two reasons. First of all - Solidarity. Solidarity created an amount of publicly minded people that never existed in any other socialist countries since at least 30 years. The older traditions were lost, and but now in Poland, I don't I wouldn't say everybody, but every educated man that is younger than 50 has somehow had something to do with Solidarity. And that means that they are publicly [inaudible]. That is one. The second thing is that party has no positive proposition, Having no positive proposition it means that they are in a sense, totally passive and only not passive idea is economy, how to change the economy. So if you do something for the economy, it's quite difficult to say that you are against the regime. That has created a very strange situation in which party is not perhaps in retreat, but... has to accept some social or even opposition propositions from the opposition. And for example, just recently, party has announced a programme of economic reforms and then Solidarity announced the programme of economic reforms. If you compare them, they are really 90 percent the same because what else can be done in a specific situation? There are only these things that can be done. To do them that is really a problem, and the retreat of the party is a very different thing from the retreat of the people of the party, and that probably would be the main problem in the future. How far all informal connections of party people with managers of big enterprises or with people who are doing changes on the private, on the opposition side or on the official side, how strong this influence of this informal mafia kind of party important is going to be. And that would be a very difficult thing to change.

So I would say Poland is exception because of two things, because of Solidarity and because of misery. They both somehow accidentally, in a sense, connect now to create this strange situation in which quite a lot is possible. And there are is a new generation of people. 15 years ago, for example, I didn't know anybody who had a private enterprise. Now I know at least 15 people, because in this kind of milieu, let's say, intellectual or intelligentsia milieu. It was suppose not to be fashionable to have a private enterprise. Now it is fashionable to gain money, which is an enormous change after, and that is the third factor, after Solidarity, after misery, I would say also a kind of liberal Western influences. So many people traveled abroad and have seen that abroad it is quite a normal thing to gain money as much as you can. So now they try to do the same thing. This perhaps often superficial, but Westernisation is also an important factor. People don't want anymore to be dependent on somebody. They even prefer to be independent and have less money, which is not very often. Not to be salaried, but be dependent.

It must have been a difficult dilemma for you to break the boycott that has been imposed here since the imposition of martial law.

Yes, of course it was a dilemma, but it was also, I think, a necessity because we thought that you cannot spend the next 30 years doing nothing. And I, my colleagues as well, we think that we are going to spend, I don't know, 20 or 30 years like that. So, because of that, we decided to start our paper once more, after several years of break and after two years of trying, we managed to obtain the official permission, which means that it will be the first, in a sense, paper which is totally independent of the state and of the church. Saying of the state, of course, not of the censorship, because we are subjected to censorship and, as everything that is published legally, in Poland. And we have to go to them to discuss with them and they confiscate some things. Which is perhaps not really so bad, because for an intellectual paper, it is of course bad that there is a censorship, but for an intellectual paper is not the worst thing in the world. The most things that are really confiscated, are things about Soviet Union and everybody knows what Soviet Union is in Poland, so it is not the most intellectually interesting subject.

What's it like for a dissident intellectual to meet with a censor?

You know, it's always this practise that probably started in 1945 that everybody makes an eye, so censor says, “you know I understand what you mean but we have to do that” and I say, “I know that you have to do that” and so in a sense it is like that. Also, it is very strange because you often don't understand why they're doing this or that, why they're confiscating this or that, because they are interested in words not in thoughts. So, if you can put the thought in another way, you can easily manage to push it through the censorship only the words, pejoratives, adjectives. That's really interesting. If you write “neighbouring country”, it's OK if you write “Soviet Union,” It's not OK, and so on. So, it's a strange feeling, but not a feeling that somebody who has spent 40 years here, in this country is very a new one.

But you don't have the impression that by entering into that game, you're jeopardising your own integrity?

No. You know, my own integrity is my problem, and I might have jeopardised that quite a long time ago. And either you feel confident that you know what you want or you not. If you don't feel, then that would be very risky. I would say that to make a compromise, of course, it is a compromise. But to make a compromise, you have to have a very strong opinion on the set of values that you are promoting. If you are unsure of yourself, you shouldn't try to get a compromise. If you are sure of yourself, why not? There is a risk, always, but the life is a risk so why don't do that? There's another risk, which is probably more important of coming slowly down because big occasions are easy, slow. Going down might be difficult, and then it's always a problem when to stop down, when to stop it. But we do hope I'm not alone. There is quite a group of about 30 people around us and we hope that such a group of people will be able to detect any signs of deterioration.

What were the concrete difficulties that you've encountered in launching the first independent journal in Poland?

Apart from political problems that was the most important, of course. But when we got political, there were thousands of administrative. First of all, it is a new thing – independent journal published by limited liability company. There's nothing like that in Poland. So, to get everything done, we've been the first. Nobody knew what to do with us. So, for example, when we wanted to registrate as a company, they said we have to have an opinion from the corporation. So, we said which corporation? There is no cooperation of private editors, of private magazines. So, after three weeks they agreed finally, and so on. To sell it abroad, we have to have a special opinion if this is an article worth selling abroad. But who can give such an opinion, as nobody has seen it, and how much can it produce, and so on. So, being the first in the field is very difficult, but also often very funny.

For more than 30 years, Polish intellectuals have been trying to become independent from the state. How independent are they today from the church?

It is a problem. You know, the problem of place. First of all, you need a space to gather, to produce theatre performances. And I'm not even speaking about movies because that really needs money and so on, but even theatre performances, art exhibitions and so on. You need the space. To have a space you need money. There are only two sources of money in Poland, State and Church, and that is one aspect of that. Another one is political aspect. There are no full of or grown-up ideological points of references. There was this state Marxism, which probably, practically doesn't exist anymore, but there is still state as such, and there is church which has its own, perhaps not ideology, but at least its own philosophy or philosophical opinion. And that is a real problem because there is not a lot of space in between. I'm quite sure that church is also not very happy about that. Church is to promote religion and to deal with religion, not to deal with cultural movies, art exhibitions and so on. Churches often, even I would say slightly, feels insecure, they don't know which paintings good or bad, which movies are good or bad. They know that people who want to produce paintings are very religious painters, but it is not quite sure that a religious painter is immediately a good painter, so church would also like to take this burden out of its shoulders. But it's not so easy because that's a problem of space. What we are trying to do is to push out, to find a bit of space for us. But it also needs money and that is also quite a problem even for a monthly magazine. For theatre, for example, it's practically impossible, although there are some new initiatives of people trying to do a private theatre, private official legal theatres that would own their own money somehow. It's not so easy, but in the West it's normal thing, so it's not impossible at least. To summarise, I would say, being a Catholic, I want to be culturally independent of the church and, of course, independent of the state. To be independent of the state is easier, in a sense that to be independent of the church, because to be independent of the church means to be in their opposition and then naturally, against the state, or at least against its ideology. And to be independent of the church, is not so easy because when you come out of the state, you are naturally dropped into the church. So, to find this space in the middle is quite a problem. But listening to people and having now a lot of voices of younger generation, I see that it is quite important for people to have something, which is theirs, not church owned, not state owned, but owned by them.

One of the aims of the opposition until recently has been to increase the autonomy of civil society. Is it still the aim of the opposition? And if yes, in what framework can this be achieved?

You see it’s not very easy to explain because there are two notions – of civil society and of the so-called alternative society, which are not the same. Civil society exists everywhere in all Western democracies. Alternative society means another society than the society created by the state in the communist countries. You could have an alternative education for example, you can have alternative poetry readings, but it's very difficult to have alternative movies, and it's impossible to have alternative economy, of course. So, if we speak about civil society then it means that we want to create a normal life on the low level of public engagement in anything, first of all, in politics. I think it is still the aim, although some people doubt that it is possible to achieve. I think some things are possible to achieve. You cannot achieve all of the aims. Perhaps the most difficult problem to obtain, aim to achieve is to get the political freedom on the high level, but on the lower levels there is quite a lot to be done and I think there is quite a lot that is already done. By people who create private enterprises, by people who tried to create associations for different things, ecology and so on, but also economy, also education and so on. All these aims cannot be achieved inside the church or inside the state. To achieve them you need what Tocqueville called the freedom of associations, and that is probably the most important problem now in Poland, because we have obtained quite a lot of freedom of speech and of writing. Of course, censorship still exists, but relatively, this freedom is quite strong and there is quite a lot of that. The next step would be the freedom of associations and, at least for me, it is the most important step to take now, and that is the proof of how democratic or how democratising this state is. If they allow that, or at least allow half of the projects, that would be enormous achievement. But it depends on the frame of mind and there are people who think that you cannot talk with the devil. If you think that the communism is a devil as President Rheagan once said, or evil, then of course you cannot compromise with evil. You shouldn't. If you think that it is in a sense a reality in which we exist, then you have to look for some compromises, and that is quite a problem. There are people in Poland who think that you shouldn't compromise. Although, in my opinion at least, they forget that there are people who have to compromise.

Mr. Król (?)