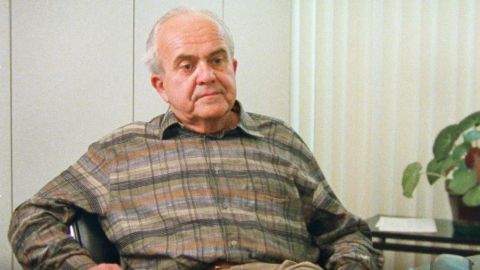

Antonín J. Liehm, ?

Questions to the narrator

- 00:09--

- 01:46The freedom from the censor and the freedom from the market, are these the conditions for the emergence of the new wave?

- 02:17One of the impressive things about the new wave is that it didn’t produce just one, two or three films. It produced twenty great films, among the best known ones are The Firemen’s Ball, The Party and the Guests, My Good Countrymen. What do you think these

- 05:38Was there another reason that made the new wave powerful, that there was lot of interaction of writers, filmmakers, of all the artists, that were all converging towards the film industry?

- 06:13Could I be more specific about some of the films? The Party and the Guests – why was the film so significant and in particular, why was that last sequence considered so powerful for you?

- 08:51So that is one parable, but you said there were two.

Metadata

| Location | ? |

| Date | |

| Length | 10:47 |

Watch and Listen

| Full video (mp4, 10 min) |

| Preview video (mp4, 1 min) |

| Audio track (mp3, 10 min)

|

TranscriptPlease note that this transcript is based on audio tracks and doesn't have to match exactly the video

(…)

Thus when the system started breaking up, and the leaders of the system and eventually on all levels ceased to be certain and sure of what was going to happen tomorrow, of course the surveillance became much less strict, so eventually the system started regaining its positive qualities: public subsidy, independence of the market, interest in art. And the creators of film, that means the filmmakers and the scriptwriters, were getting more and more control of the industry and of productions. So I would say the nationalised system, the state system of cinema, the public subsidised system, could be the worst of all if it’s very tightly supervised and ruled. But on the contrary, as the Czech director Ivan Passer, now living in the United States, once said: When the system falls apart this is the best system you can ever have. And the filmmakers were never so free, relatively free, as they were in the 1960s in Czechoslovakia, and that showed. Of course that is not true only about Czechoslovakia, it’s true of all other film industries in the East at different moments, for different periods of time. The same thing eventually happens, and I believe that something like that is also happening today in the Soviet Union.

The freedom from the censor and the freedom from the market, are these the conditions for the emergence of the new wave?

Freedom is probably a very big word but I would say certain relative independence. Because relative independence from the market, for instance, in the West you don’t have it at all, so that means the market is an enormously powerful censor and the situation’s very complicated. We cannot go into the details here.

One of the impressive things about the new wave is that it didn’t produce just one, two or three films. It produced twenty great films, among the best known ones are The Firemen’s Ball, The Party and the Guests, My Good Countrymen. What do you think these films had in common? What was the common denominator that made them so powerful?

I believe that since Lenin once said that film was the most important art for us, that means the Bolsheviks, film gained obligatorily a very important place and position in all socialist cultures. And I would say for instance in Czechoslovakia since the 1930s, the best artists from all different disciplines eventually gathered and coalesced around film. This very positive development of Czech film as an art form was stopped twice, once in 1938–1939 and for the second time in the Stalinist era after 1948, and for different reason again once more in 1958. That means that in the 1960s three generations of Czech filmmakers eventually got the chance for the first time in their lifetime to do what they wanted to do. That’s why you had, you said twenty films, I would say you had practically fifteen directors of all generations. Some of them were sixty – the oldest one, and the youngest ones were little over twenty, and they were doing exactly the same thing but with different experience, with different styles but within the same framework. And I believe that was the reason why this small film production, which was the Czechoslovak film production in the 1960s, became one of the most important in Europe. Look, in 1968, Czechoslovakia, or Czechoslovak film, was represented in the main competition of the Cannes film festival by three films. That never happened to another film industry but the American, the French and the British, or Italian, once or twice. So that means that was disproportionate if you wish, but there were reasons for that. Now all that was unfortunately destroyed completely after 1969 in the “normalization period”. Not only the filmmakers, not only their ambition, but also all sequels, I would say, of this marvellous creative period of the 1960s were wiped out and burnt out.

Was there another reason that made the new wave powerful, that there was lot of interaction of writers, filmmakers, of all the artists, that were all converging towards the film industry?

That’s what I said, in the 1930s it had already happened, and it came back in the 1960s. And as Prague is of course a small place but an enormously inspiring place and these people, that means writers, painters, musicians, filmmakers meet each other twice every day, so then eventually the interaction is enormous.

Could I be more specific about some of the films? The Party and the Guests – why was the film so significant and in particular, why was that last sequence considered so powerful for you?

You had basically three ways. Czech films were never overtly political. They were metaphorically political. And three different approaches developed during the 1960s. One was, I would say, the kind of a fable approach. It was a thoroughly metaphoric approach which would not try to describe the actual situation but choose a poetic metaphor which would eventually show mainly the structures of the situation. The Party and the Guests was probably the most significant of those because through a parable, through a poetic metaphor it eventually showed the functioning and the moral structure of the Stalinist system. You have the centre of the party in the film, you have a feast, you have a big dinner, where everybody is invited to be happy and at the same time declare their loyalty to the man whose birthday is being celebrated. And the whole celebration is taking place in very awkward conditions in a swamp with food which is not so good, with people who got there under very difficult circumstances, eventually their attire is torn and they are not that happy, not as happy as they should be. And at the moment when one of them eventually gets up and says, well OK, I’m not interested, and starts walking away, so then they all realize that if one walks away they are all compromised. So they chase him, they start a chase with dogs and everything, because somebody broke this silent loyalty and somebody decided that he will act as an individual, which is terribly dangerous for the majority.

So that is one parable, but you said there were two.

The other one is irony. You have some satirical films which were not so good but you have ironic metaphors. The master of the ironic metaphor is Miloš Forman obviously. And again Miloš Forman eventually tried to describe small chunks of life which, under the microscope of his camera and of his poetic imagination, become a fantastic portrait of society. I like to tell my students that when I was a child, my uncle, who was a university professor of biology and anthropology at medical school, invited my family to lunch. I was, I don’t know, 4 or 5 years old and didn’t wash my hands before lunch. And my uncle, the professor, took me by my hand and took me in his lab and put my little finger under the microscope and said, look. And I looked at my finger and what I saw was so horrifying that I started washing my hands not only before lunch but again and again. And I think that’s exactly what Forman is doing. He’s putting a little finger of society or a few square millimetres of society under the microscope, like in Firemen’s Ball, like in Black Peter and so forth, and shows what society looks like. The Firemen’s Ball, which is really telling a funny story of a ball, of a celebration – [unfinished]

Antonín J. Liehm (1924–2020)

Literary and film reviewer, translator and journalist

After grammar school, he graduated from the Political and Social University in 1949. After the war, he contributed to the Kulturní politika [Cultural Policy] weekly, which was later banned. In 1948 he began working for the press department of the Ministry for Foreign Affairs, but was fired a year later. During his military service, he worked in the Naše vojsko army publishers; later for the foreign department of the Czech News Agency (ČTK) and eventually again for several years at the Ministry for Foreign Affairs. In the 1960s he was one of the chief editors of Literární noviny [Literary Journal] and headed its film section. The occupation of Czechoslovakia by the Warsaw Pact armies in August 1968 brought a halt to the social changes of the Prague Spring and was also the reason why he went into exile. He settled in Paris and taught at universities in Paris, New York, Philadelphia and London. In the 1980s he was the editor of the periodicals 150 000 slov [150 000 Words] and Čtení na léto [Summer Reading]. He founded the international cultural revue entitled Lettre Internationale which he published in 1984–1988. The French version was extended with Italian, German, Spanish and Serbo-Croatian versions and, after 1990, also with Czech, Russian, Hungarian, Romanian, Bulgarian and Croatian versions.

Generace [Generation] is a collection of interviews he conducted with personalities such as Milan Kundera, Ludvík Vaculík, Ivan Klíma, Jaroslav Putík, Jan Skácel and also Eduard Goldstücker and Václav Havel (in German, Vienna 1968; in Czech, Cologne 1988). He used his knowledge of film in the book entitled Příběhy Miloše Formana [Stories of Miloš Forman] (New York, 1975; in Czech, ’68 Publishers, Toronto 1976) and a collection of interviews with filmmakers entitled Ostře sledované filmy [Closely Watched Films] (in English, New York 1974; in Czech, NFA 2001). The experiences of his generation are reflected in his autobiography Minulost v přítomnosti [The Past in the Present] (Host 2002). He translated works by Louis Aragon, Jean-Paul Sartre and Robert Merle into Czech. After the fall of communism, he was a member of the editorial board of Mosty [Bridges], a Czechoslovak weekly, and chairman of the editorial board of Listy. In 2013 he moved back to Prague.

He is the holder of the Tom Stoppard Prize for 2015, and in October 2015 was awarded the Medal of Merit by president Miloš Zeman.