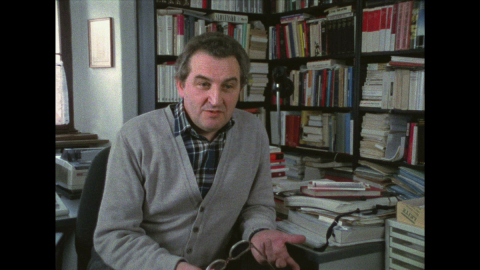

Vilém Prečan, 31. 1. 1988, Scheinfeld, Germany

Questions to the narrator

- 00:08Why was there a need for such an archive of Czech independent culture in the West?

- 01:06Why was there a need for an archive of Czech culture in the West, a place where all the samizdat publications would be collected?

- 01:50You have credited the famous Black Book written shortly after the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia. This was the first attempt to produce a historical record of an instant, of an event that had just taken place. What’s the special role of the historian i

- 02:53Because you felt that that record was threatened, that everyday history was being re-written by the official propaganda?

- 03:23How many journals are produced today in Czechoslovakia, how many samizdat journals or publications?

- 03:46And how many books have been produced like that in samizdat, let’s say over the last 10 or 15 years?

- 04:30That cannot be published in Czechoslovakia?

- 05:10Could you tell us about your own personal history? What happened to you after the publication of the Black Book?

- 06:30Writing history was considered to be a subversive activity?

- 07:07Why do you think the authorities were so sensitive to your undertaking?

- 07:31How come historians have become one of the prime targets of normalisation, sacked from their jobs, etc.?

- 08:54Why is it important to have the archive here in the West?

- 09:15But what’s the bigger idea behind collecting all the material? Why is it important to gather all this material for you?

- 10:16Is unofficial culture particularly vulnerable to being destroyed, is it?

- 10:42And what happened to you, after 1968?

Metadata

| Location | Scheinfeld, Germany |

| Date | 31. 1. 1988 |

| Length | 11:47 |

Watch and Listen

| Full video (mp4, 11 min) |

| Preview video (mp4, 12 min) |

| Audio track (mp3, 1 min)

|

TranscriptPlease note that this transcript is based on audio tracks and doesn't have to match exactly the video

Why was there a need for such an archive of Czech independent culture in the West?

I’ll show you an example. It is the problem of how to document independent publishing, how it works. For instance, this is the well-known essay by Milan Šimečka, The Restoration of Order. This is the original typed manuscript, and this is the samizdat edition, signed by the author, with his photograph, of course typewritten but well bound, and then a printed book in Czech, and then different foreign editions, in English, in French, in Italian.

Why was there a need for an archive of Czech culture in the West, a place where all the samizdat publications would be collected?

Naturally this archive belongs to Czechoslovakia, it should be located in Czechoslovakia, but the actual situation makes it impossible. It would be confiscated and destroyed. Instead of there, it’s here for the time being. We hope sometime all these collections and archives will be back where they belong, in Czechoslovakia.

You have credited the famous Black Book written shortly after the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia. This was the first attempt to produce a historical record of an instant, of an event that had just taken place. What’s the special role of the historian in a period like the one that Czechoslovakia has known, since the invasion?

Not to let the evidence be destroyed, to collect it, to put it together, and to present it to the public. That’s not only their right but it is their duty. And it is the feeling of the duty which was the main reason why we tried to document the events, the seven great days of the Czech and Slovak nation in 1968.

Because you felt that that record was threatened, that everyday history was being re-written by the official propaganda?

Not only this, but we wished to give an impulse that in all the regions, in every town and in every factory, this material would be safely preserved and collected.

How many journals are produced today in Czechoslovakia, how many samizdat journals or publications?

Now? Currently at least three dozen published periodicals. Some of them are monthly, some of them are quarterly, all sorts, something like this.

And how many books have been produced like that in samizdat, let’s say over the last 10 or 15 years?

Oh, I would like to know! Only one samizdat series, the well-known “Edition Padlock”, now has 366 titles by the end of 1987. And there is Edice Expedice with about 280 titles and there are Česká expedice, Edice Popelnice and others. I think it’s perhaps 1,000 books.

That cannot be published in Czechoslovakia?

They could not be published in Czechoslovakia but they exist, they have their readership. They are reprinted then in the West by exiled publishers, they are translated, it means they become part of world literature, of contemporary world literature, they are available. Czech and Slovak independent writing is not silenced.

Could you tell us about your own personal history? What happened to you after the publication of the Black Book?

Nothing at that moment, but later in the course of so-called normalisation, in 1970 in spring, I was dismissed from the Institute of History of the Czechoslovak Academy of Sciences in Prague, together with a couple of my colleagues. Actually, the whole Department of Contemporary Czechoslovak and World History was re-organised away from the Institute, it means it disappeared. In 1971, I and two of my colleagues were accused of subversive activities against socialism and against the socialist order.

Writing history was considered to be a subversive activity?

Preparing this book … It was not written, it was only documentation, it was documentation on the invasion and how the people in Prague and in Czechoslovakia reacted. We documented not only the resistance of the population, we recorded and documented what the Soviet mass media said and what they claimed, and it was not one-sided.

Why do you think the authorities were so sensitive to your undertaking?

Why? Because it was the truth about what actually happened, and not what they wanted people to believe that happened.

How come historians have become one of the prime targets of normalisation, sacked from their jobs, etc.?

There are many reasons. One of them is ideological, the Marxist-Leninist ideology is a historical ideology. Secondly, because the regime has no legitimacy in free elections, it bases its legitimacy on the history of Czechoslovakia, the legitimacy it gained in 1948. And thirdly, historians seeking the truth and telling the truth, what actually happens, they are conflicting with the aims of the actual politics or the actual line of the latest interpretation from the last session of the Central Committee of the Communist Party.

Why is it important to have the archive here in the West?

Because such an archive cannot be built up or work in Czechoslovakia. It is for the time being that it must be placed here in the West, in safety. That’s all.

But what’s the bigger idea behind collecting all the material? Why is it important to gather all this material for you?

It is important. There are many reasons, one of them is to preserve it, then to make it available to anybody who needs to consult it. We are making copies of these materials and we are making them available to libraries, to researchers, to publishing houses, to journals, etc., etc. And thirdly, what was not published so far now must be published. And it must be studied, therefore, it is important.

Is unofficial culture particularly vulnerable to being destroyed, is it?

Oh it is, because there are no institutions in Czechoslovakia that preserve these materials. It is confiscated in every house search, in dissidents’ houses, it is destroyed by the police. It was confiscated, some of these manuscripts no longer exist, the authors themselves don’t possess these materials. So it often happens that I am asked by the authors in Czechoslovakia to send them a copy of their own work because they don’t have it.

And what happened to you, after 1968?

In the spring of 1970 I was dismissed from the Institute of History together with a couple of my colleagues, and then I was unemployed for some time. And then I worked in a couple of jobs, mostly as a stoker in a Prague hospital. In 1975 I decided to fight for emigration. I wrote an open letter to the World Congress of Historians in San Francisco describing the situation of historiography in Czechoslovakia after purges. And then eleven months later, I was allowed to legally emigrate with all my family from Czechoslovakia in July 1976.

Vilém Prečan (1933)

Vilém Prečan (1933), prof., PhDr., CSc.

A graduate of the University of Political and Economic Sciences, he addressed the topic of the Slovak National Uprising and relations between the Czechs and Slovaks in the 1940s when he worked at the Institute of History of the Czechoslovak Academy of Sciences in 1957–1970. He was prosecuted for his contribution to the proceedings book entitled Seven Days in Prague, which documented the invasion of Czechoslovakia by Warsaw Pact armies in August 1968 and was dismissed from the Institute in 1970. He worked in various manual occupations and at the same time published his articles in exile press and in samizdat. In 1976 he and his family decided to emigrate to West Germany, where he founded the Czechoslovak Documentation Centre, a place where collections of samizdat and exile literature were stored, in Schwarzenberg Chateau in Scheinfeld in 1986. He collaborated with leading personalities of the exile and Czech opposition around Charter 77 and played an important role in the exchange of information and documents across the Iron Curtain. After his return to Czechoslovakia in 1990 he founded and became director of the Institute of Contemporary History of the Czechoslovak Academy of Sciences and founded a scholarly journal entitled Contemporary History (Soudobé dějiny). He became a member of the scientific board of the newly founded Institute for the Study of Totalitarian Regimes. He holds many awards. In 1998 President Václav Havel awarded him the Order of Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk.

For more, see csds.cz/cs/g6/5056-DS.html