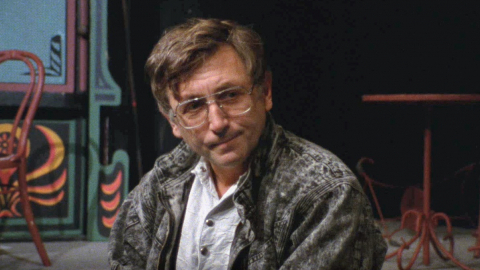

Jiří Menzel, 18. 1. 1988, Prague, Czechoslovakia

Questions to the narrator

- 00:12Is there a continuity in your work from Closely Observed Trains to the latest film, My Sweet Little Village?

- 01:15Closely Observed Trains was the highlight of the new wave of the 1960s. What were the common features of the new wave? There was such a great diversity among them.

- 02:01Why do you think these films are important?

- 03:05And what is the meaning of these films from the 60s for you today?

- 04:06So is one of the features of the new wave that it discovered real people with real lives?

- 04:39But what do they tell about the society of the time? You said they reveal things about people and about society, what do they tell us today about society?

- 05:29You are very modest about your own work, about Closely Observed Trains, but there was not just one film, there were several great ones.

- 06:58What were the conditions here?

- 08:48So it is also that the people who were deciding about the fate of Czech film making suddenly felt more relaxed and were wiser? How would you explain that?

- 10:03You mentioned the box office success of these movies. So what was the social impact of the new wave of the sixties?

- 13:12You mentioned what happened to Western cinema but what happened here? What has happened to Czech cinema over the last twenty years?

- 14:16Was putting stamps on a beautiful girl's bottom part of the sexual freedom that the new wave of the sixties also presented?

- 15:15But the scene was considered daring then because it was breaking the puritanism of the 1950s.

Metadata

| Location | Prague, Czechoslovakia |

| Date | 18. 1. 1988 |

| Length | 16:04 |

Watch and Listen

| Full video (mp4, 16 min) |

| Preview video (mp4, 1 min) |

| Audio track (mp3, 16 min)

|

TranscriptPlease note that this transcript is based on audio tracks and doesn't have to match exactly the video

Is there a continuity in your work from Closely Observed Trains to the latest film, My Sweet Little Village?

There has to be continuity as it was made by one person. And if I try to be as sincere as possible in what I am doing, these films cannot be far apart. The films in between have not necessarily been so successful, but I think there is a common thread in them. A film is always influenced by the conditions in which it is created. Of course the storyline is important, but so are also all the cultural and historical conditions at the time the film is created. So I have the impression that I could not have made My Sweet Little Village then, and I could not make Closely Observed Trains now. But I think all these films have something in common.

Closely Observed Trains was the highlight of the new wave of the 1960s. What were the common features of the new wave? There was such a great diversity among them.

I have to say that it is the impression you get because it is the most important and most often awarded film. But a number of films were made besides that, which I rate very highly, which may not be as successful in international terms, but which I think are deeper, especially those made by Schorm, but also for instance Intimate Lighting by Ivan Passer and early films by Miloš Forman.

Why do you think these films are important?

Because when you watch them today they still raise your interest in the people you see on the screen. They still arouse what dramatic art should arouse – the interest in the story which is being presented. And those films are a testament to the time in which they were created but are still valid today, they still excite. Coincidentally, I saw The Loves of a Blonde in America on TV. And in the amount of rubbish which was aired there, I suddenly became fascinated and watched this black and white film, this beautiful story. I was there with my friend, the movie director Svěrák, who said, “This is like a spring of clear water.” A film which is some twenty-five years old.

And what is the meaning of these films from the 60s for you today?

Just what they meant for me then. It is just like good literature or good drama. It is telling a story about people, a testament to what we are like. And that’s the best way of knowing oneself and the people around us. This is the mission of these types of art, literature and drama, because their object, the object of learning in these films, is man. And this is particularly true of good literature, French or Russian, and also of good films, French, or Italian neorealist films. And it’s also true of the films that I have been talking about.

So is one of the features of the new wave that it discovered real people with real lives?

Yes, exactly. And it is not just about “real life”. There are also films which are a bit fictitious, they are fairy tales, for instance some Hollywood films, such as High Noon or Stagecoach. They are not realistic movies, but they reveal something about people and their character, they tell stories about people –

But what do they tell about the society of the time? You said they reveal things about people and about society, what do they tell us today about society?

– Even though I don’t know the reality in America back then, it tells me something about relationships between people, and thus also about their social background. Of course with the realistic films, such as Intimate Lighting or the Firemen’s Ball, it is a very beautiful testimony. But even fairy tales recount something even if they may be completely silent about reality. In this silence, they still say something about reality, as if they give a negative picture of reality.

You are very modest about your own work, about Closely Observed Trains, but there was not just one film, there were several great ones.

But this is what always happens. When you look back at the history of film, you will see that every nation has an era when very good films were made. Take for instance the 1930s in France, the French new wave, or some periods in America. Many wonderful films are made. And you can forget the other eras. Neorealism in Italy … Suddenly there are conditions, a kind of symbiosis of cultural, historical, political and economic conditions, which allow talents to develop. In France, for instance, the French new wave was boosted, as far as I know, most importantly by a law which enabled financial support for French cinematography. And straight away people who normally wouldn’t have had the money to make films got it and could make films. Along with it came technical developments that made it much easier to shoot a film, as it became possible to work with lightweight cameras, with film material which made it possible to shoot without expensive and complicated lighting, and they could enter a real setting with the camera. It happened here later, too.

What were the conditions here?

It was linked here with cultural and historical conditions. Until then some things were not talked about, so there was a certain build-up and a desire to speak about what life was really like. But I remember that it was not only all of us at film school who scorned a little what was showing on the screens or written in the newspapers. There was a saying, “This is like shooting a film” and you’d use it to say that something is not completely true. And then came a great desire to really say something true, something real, with the film. And I remember what a discovery for us then were the American documentaries in the late 1950s and early 1960s, which showed us how to use the new light cameras and how to get “inside”. Shadows by Cassavetes was a great discovery for us, compared to those films where lots of make-up was used, made in studios and with studio lighting. And all this, as well as a number of other influences, led to a whole generation that suddenly knew not how to make films but what kind of films they did not want to make. There was agreement on this. And along with it there came the miraculous circumstance that suddenly there were leaders of cinematography who listened to this and gave these filmmakers support and trusted them, and made it possible for everyone who had just graduated, like me for instance, to make a feature film right away. That was a miracle. At least compared to the times that came after or before that.

So it is also that the people who were deciding about the fate of Czech film making suddenly felt more relaxed and were wiser? How would you explain that?

They had the courage and enough reason to be able to listen. The people who came to become leaders of cinematography had not come from film, they had come from elsewhere, but they were, I’d say, enlightened. And what’s also important, the power was not centralised. At that time films were produced by six competing units, each of them wanting to make a better film than the others. And they knew they would make better films with young people, and that’s why they trusted them. And naturally this was coupled with the immediate box office success that the films had. Films by Miloš Forman and Věra Chytilová were successful at festivals and that gave them prestige, and so it was all possible.

You mentioned the box office success of these movies. So what was the social impact of the new wave of the sixties?

This is connected because when a film is doing well at the box office it means that people go to watch it, and if the film is good it influences people. And these were intelligent films and, you could say, films which induce cognition. I travelled to a number of debates then with film as well as non-film fans and found one thing which I could later compare with my stays abroad: there is a significant group of people in Bohemia who are not intellectuals, scientists or highly educated people, they may be workers, but they are not stupid, they read a lot, they are educated in a way, or partially, as much as it is possible here, and they are able to understand film and discuss it. And films, not only Czech films, had a great effect on this. Naturally it was also literature which was widely translated here. And all of this put together provided a very good cultural background to create not only film, but also theatre and literature. And it’s a pity that the era did not die a natural death. It wouldn’t have lasted long anyway, because it’s a rule that nothing lasts forever, but it’s a pity somehow because the films were highly regarded abroad and to some extent also influenced other film makers. At least that’s what my foreign colleagues told me. And it’s a pity that it was interrupted because the films had something special, something with which they could influence foreign cinematography. By this I mean mainly Miloš Forman, Věra Chytilová and Ivan Passer. What made their films specific or typical, apart from being intelligent and having humour, was that they had a strong humanist charge, an interest in man. There was not merely an aesthetic reason or intellectual search in them. There was a real interest in man, his life and how people treat one another. And unfortunately when the new wave disappeared in the early 1970s, the whole world, or at least Western Europe and America, changed course and went in the direction of dehumanisation – violence, sex, appeal to primitive urges, and that happened not only with commercial films but even intellectual ones.

You mentioned what happened to Western cinema but what happened here? What has happened to Czech cinema over the last twenty years?

Here we unfortunately returned to the era of studio films that wanted to be true but were miles away from the truth, and that went on like this for long. This is always related to cultural and historical conditions, as at a certain time something comes which I call the fear of truth, the fear to look at things the way they really are. This happens to everybody a couple of times in their lives, and to the nation in its history. And that unfortunately greatly affected our cinematography for a long time. But now I think it is going back to the old ways. I’d say there is something to build upon, mainly the films by Forman, but also by Jireš, Jan Němec, Ivan Passer, and so on.

Was putting stamps on a beautiful girl's bottom part of the sexual freedom that the new wave of the sixties also presented?

Firstly, that is a story that really happened then in wartime, and it is also a testament to how much the world has changed. By coincidence, last Saturday night on television they broadcast a collection of sex scenes from Czech films, and this scene was included. And however daring it looked then, it looked so innocent among these scenes from Czech films now, I’d say like something for children.

But the scene was considered daring then because it was breaking the puritanism of the 1950s.

No, because Forman had shown a naked girl in film before. The point was only that it was all so innocent and open that the girl pulled her knickers down herself. But I’d say that after that, much worse things began to be shot.

Jiří Menzel (1938–2020)

Film director, actor and writer

He graduated from the Film School of the Academy of Performing Arts in Prague. His very first feature film made him one of the most important representatives of Czechoslovakia’s New Wave of film in the 1960s. Closely Observed Trains (1966), shot according to a story by the writer Bohumil Hrabal, won him an Oscar. He used a story by the same writer to shoot Larks on a String (1969), a movie about a group of female prisoners working at the scrap plant of the Kladno ironworks in the difficult 1950s which ended up being banned for twenty years after the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia in August 1968. He was awarded the Golden Bear for the film at the Berlin International Film Festival in 1990. He was also a theatre director from the 1970s and worked for the Činoherní klub and Na Vinohradech theatres and lectured at the Film School from which he had graduated. His other popular films are Na samotě u lesa (1976, Secluded Near the Woods), Postřižiny (1980, Cutting It Short), Slavnosti sněženek (1983, The Snowdrop Festival), Vesničko má středisková (1985, My Sweet Little Village) and Obsluhoval jsem anglického krále (2006, I Served the King of England).