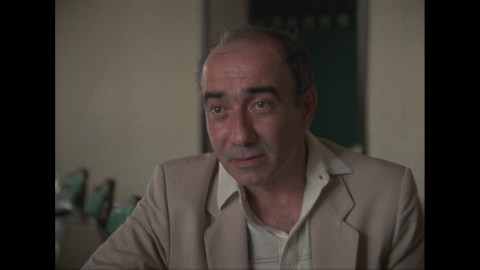

László Antal, 2. 7. 1987, Budapest, Hungary

Questions to the narrator

- 00:06A move towards full marketization of the Hungarian economy implies a retreat of the party from the economic sphere. How far can the party retreat?

- 01:31Gorbachev advocates closer integration of the Comecon, while talking of economic reform. There might be a slight contradiction between these two elements of his rhetoric. What's the Hungarian response to this? How compatible is your program, your reform w

- 05:24Your report says that there can be no economic reform without political change, without political reform. What is the connection between the two? And why is political reform the key to economic reform?

Metadata

| Location | Budapest, Hungary |

| Date | 2. 7. 1987 |

| Length | 06:58 |

Watch and Listen

| Full video (mp4, 6 min) |

| Preview video (mp4, 1 min) |

| Audio track (mp3, 6 min)

|

TranscriptPlease note that this transcript is based on audio tracks and doesn't have to match exactly the video

A move towards full marketization of the Hungarian economy implies a retreat of the party from the economic sphere. How far can the party retreat?

/To the interpreter: To what extent did it retreat? Interpreter: to what extent can it retreat. /Well, this is a serious problem of our reform program. The program itself, the program we prepared, states that the division of labour, the allocation of roles between party and state needs to be changed. The economic role of the state must be circumscribed clearly and the party should indeed concentrate exclusively on theoretical guidance, in other words on long-term strategies. If we cannot reach that, then it will be very difficult indeed to envision the introduction of a market-oriented reform. Nevertheless, I do think that there is a chance for this now. And I’m saying this with the recent international changes in mind, including developments inside the Soviet Union, all these creating a more favourable environment for this reform. I must also include the fact that the Hungarian economy is in a very bad shape, this also being a compelling force for us not to ruin the economy by uncoordinated and far too meticulous leadership.

Gorbachev advocates closer integration of the Comecon, while talking of economic reform. There might be a slight contradiction between these two elements of his rhetoric. What's the Hungarian response to this? How compatible is your program, your reform with Gorbachev's call for closer integration in the Comecon?

The developments in the Soviet Union have a twofold effect on us. The political chances create a favourable atmosphere for the Hungarian reform efforts. On the other hand, the determination to get Comecon to a stricter cooperation undoubtedly causes serious problems. Nevertheless, there are proposals that include the modernization of the CMEA-mechanism which isn’t initiated by Hungary, but by other countries, primarily the Soviet Union. In this case much better forms of cooperation would be possible. Today, as long as the role of money is minimal in Comecon relations, we’re considering to connect the Hungarian producers and Soviet partners through firms acting as trading houses. Therefore, we should interpose trading houses that would mitigate the problems and tensions arising out of the differences between the two mechanisms. /To the interpreter: This was difficult, I can’t help it./

The real problem is that money doesn’t function when it comes to economic relationships with socialist countries. If money-based trade were possible, then there would be no obstacle in the development of commercial relations. The problem here is that they want to tighten relationships through non-financial planning instruments, or with largescale development programs. Therefore, not the key concept is the question, namely that there should be significant commercial relationships between socialist countries. The real question is that this economic relationship should be established in a system of cooperation where money-based trade doesn’t function, where market doesn’t work. In this manner, firms producing for the Comecon will very soon cease to be competitive and will remain technologically underdeveloped, so this is a question of mechanism as well. Therefore, we think that if within the Comecon tendencies will strengthen to gradually turn the transferable rouble into a convertible currency, it will be possible to have a cooperation on a rational basis within the Comecon market as well. Until then we could try establishing such trading houses that will be business partners to Hungarian firms, but will trade directly with Soviet partners, that is, we’d interpose these trading houses into the direct interrelation of companies. That way we’d hope to alleviate the contradiction that – as I’ve said, – isn’t primarily an inconsistency of economic policy, Gorbachev’s policy doesn’t exclude an opening to the West. The key problem is the rationalization of Eastern connections, that is in need of a solution, this is the root of the contradiction.

Your report says that there can be no economic reform without political change, without political reform. What is the connection between the two? And why is political reform the key to economic reform?

There are multiple reasons. First of all, the economy is in such a difficult situation that it’s impossible to carry out a reform program without consulting the society. It doesn’t work if a small, tight group elaborates the details and attempts to convince everyone later on about implementation. A program which requires sacrifices from the society can only be made accepted through open social debates. The other reason is the an efficient functioning of the economy entails the clarification of the relationship between party and state, the strengthening of the role of Parliament, and in any case the creation of solid guarantees. All in all, it isn’t merely an economic issue, and also the question of who becomes leader is a very important one. These issues cannot be separated from the operation of political institutional systems. Besides, this has already been proved by a number of theoreticians like Bruce for example, that no such artificial separation of social and economic problems exists.

László Antal (1943)

László Antal, a world-renowned economist, was born on 22 January 1943, and died on 26 September 2008 in Budapest. He graduated from the Karl Marx University of Economics in 1967 with a degree in finance. After graduating, he began his career in the one-time reform workgroup of the Ministry of Finance. He was one of the masterminds and developers of the Hungarian economic reforms introduced on 1 January 1968. From 1968, he worked in the Economics Department of the Ministry of Finance, edited the Pénzügyi Szemle (Journal of Public Finance Quarterly), and was then appointed ministerial advisor. Between 1977 and 1987, he was the head of the academic department of the Institute for Financial Research, and from 1987 to 1988, he was the deputy head of it. Between 1982 and 1985, he got involved in the management of capital flow research at the Institute of Economics of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences. He signed the economists’ petition for Bálint Magyar, and in 1984, the letter of the eight addressed to the Central Committee. In 1985, he attended the opposition meeting in Monor.

Between 1989 and 1990, he was Chief Government Adviser in the Secretariat for Economic Policy of the Council of Ministers, head of the Board, and in 1989 he was appointed Deputy Minister.

He contributed to the formation of the Új Márciusi Front (New March Front) at the time of the regime change. He was on the national list of the Alliance of Free Democrats in the 1994, 1998 and 2006 parliamentary elections.

In 1990, he became a senior researcher at the Institute for Business Cycle and Market Research, and in 1992, he was appointed presidential advisor to the Hungarian Foreign Trade Bank. In 1990, he was a founding member of the Central European Economic Research and Consulting Ltd.

Since 1997, he has been working for various institutions: he was the chairman of the supervisory board of the Budapest Financial Centre, he was a member of the Finance Committee of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, the editorial board of Napi Gazdaság (Economy Daily), and chairman of the finance department of the Hungarian Economic Society.

In his academic publications, he focused on the topic of Hungarian capital flows and sustainable growth. He was the author of several fundamental works: the Fejlődés – kitérővel (Development – with Bypass) from 1979 and Gazdaságirányítási és pénzügyi rendszerünk a reform útján (Our Economic Governance and Financial System under Reform) written in 1985 are works in the lack of which it would be difficult to understand the economic and political conditions of the 70s and 80s. His last book, Fenntartható-e a fenntartható növekedés? (Is Sustainable Growth Sustainable?) published in 2004, is a meticulous report on the transformation of the market economy.